Letter from Africa: Why Africa needs the United Nations

- Published

- comments

In our series of letters from African journalists, film-maker and columnist Farai Sevenzo considers why the UN matters to Africa.

If the 70th UN General Assembly had a face, it would not only be showing its age, but it would be covered in the cuts and bruises from unending wars, new coups and the perennial problems of poverty, hunger and the new open, weeping sores that are the movements of the desperate and despairing across oceans and borders.

For African leaders, the UN in New York is the place to be seen and heard every September.

They are there under the magical veil of diplomatic immunity, not only because their leadership is recognised but also because it allows those who are older than the General Assembly to attend, as well as those who have been ostracised by international opinion, those who have been targeted by the International Criminal Court, and those who wish to plead for special attention or show that they are tackling corruption.

Small budgets are prepared from the national coffers for the delegates accompanying the heads of state and first ladies fond of shopping, who mark the General Assembly dates in their diaries long in advance.

This year's gathering has even featured a rock star Pope, and the Catholics among Africa's leadership may have wanted to touch that holy hand, though they may not have been so keen on confession.

Keeping the peace?

Still, it does not help to be too cynical, for Africa needs the UN more than any other continent.

A brief scan of the UN's history will show us that while its predecessor, the League of Nations, threw South West Africa - present-day Namibia - from the frying pan of German occupation into the fire of apartheid jurisdiction, the UN has been largely present in tumultuous events in Africa these past 70 years.

A UN Secretary General - Swedish statesman Dag Hammarskjold - lost his life in a plane crash in the Zambian town of Ndola in 1961 on his way to peace talks in the Congolese breakaway province of Katanga.

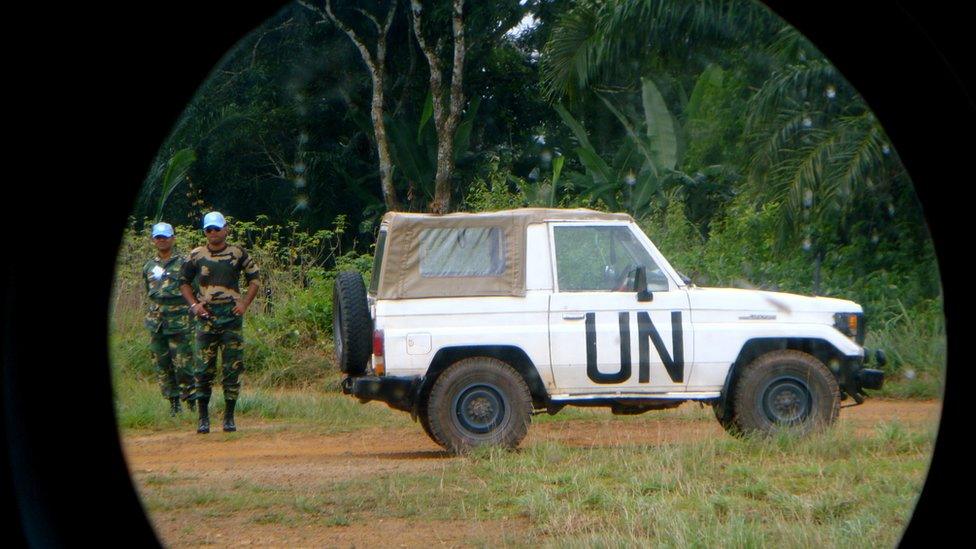

Since then UN peacekeeping forces in Africa have been a regular and needed part of the continent's story: 19,000 troops are currently serving in the Democratic Republic of Congo; 12,000 are trying to restore order to the Central African Republic, another 10,000 are deployed in Mali and the UN mission in Liberia is due to end in June 2016 - having been there since 2003.

Current UN peace missions in Africa

Central African Republic: Launched 2014, 12,000 currently deployed - Minusca

Democratic Republic of Congo: Launched 1999, 19,000 deployed - Monusco

Ivory Coast: Launched 2004, nearly 7,000 deployed - Unoci

Liberia: Launched 2003 - nearly 6,000 deployed- Unmil

Mali: Launched 2013, 10,000 deployed - Minusma

South Sudan: Launched 2011, 12,500 deployed - Unmiss

Sudan: Hybrid mission in Darfur with African Union launched 2008, nearly 16,000 deployed - Unamid

Abyei - disputed territory between South Sudan and Sudan, 4,000 deployed - Unisfa

Western Sahara - 200 deployed Minurso

The relationship between peacekeepers and Africa has been fraught with accusations of mineral theft and more seriously the sexual abuse of women and children by the international UN forces, but the security situation without them does not bear contemplation.

In 2015 a look at the headlines shows us that from Libya downwards, violence prevails.

It reveals that the fight for self-determination in South Sudan has resulted in increasing deaths after independence; Burkina Faso's presidential guard has become addicted to power and that economies wrecked by Ebola cannot do without international assistance.

World leaders have now agreed on the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), which replace the Millennium Goals, and feature many of the issues that the 20th Century grappled with.

Farai Sevenzo:

"From rising prices, to lack of pasture for cattle to drought and floods - food and hunger remain the continent's major worry"

But paramount amongst the 17 SDGs is the struggle to end hunger.

"While the number of people suffering from hunger in developing regions has fallen by half since 1990, there are still close to 800 million people undernourished worldwide, a majority children and youth," said Mogens Lykketoft, president of the 70th session of the UN General Assembly.

Of course hunger has not arrived unannounced, the state of the planet and the effects of global warming have been playing havoc with people's crops all over southern Africa.

Malawi, the UN World Food Programme (WFP) has warned, faces its worst food crisis in 10 years, external.

The WFP says 2.8 million people are at risk and that an astonishing four out of every 10 Malawian children are suffering from stunted growth.

Poor rainfall affected the crops in 2013/2014 and then floods compounded the problem in early 2015 by destroying homes and wiping out food supplies.

Schoolboy Gift Charles talks about his life in a small village in Malawi and his hopes for the future.

USAid's Famine Early Warning System has also listed food shortages in Ethiopia and Somalia, as well as in Sierra Leone and Liberia following the outbreak of Ebola.

From rising prices, to lack of pasture for cattle to drought and floods - food and hunger remain the continent's major worry.

Those attending the Sustainable Goals event spoke of its wide scope; UN chief Ban Ki-Moon said the new development blueprint was designed to "resonate with people across the world", while UN Development Programme head Helen Clark said the goals called "for a paradigm shift in how the international society understands development".

Naomi Grimley outlines the 'Global Goals' - in 75 seconds

Development, if truth be told, has sometimes been hampered by some of the very people who gather every September in the autumn sunshine.

But it is their solemn duty - and ours - to try and develop ourselves.

At its worst, the UN is a grey monolithic beast that is overstaffed with career diplomats and "angels of mercy" who run around African cities in their 4x4s on behalf of Western charities and their own ambitious career paths.

But at its best, the UN is the last refuge for the powerless, the hungry and the needy.

And Africa has far too many people in all three categories to do without it.