What is nature?

PDF

Nature is a common notion, which everyone is familiar with as long as we are not asked to define it. This is normal: there is no consensus definition of it, and the term is rejected by most academic disciplines in both the sciences and the humanities. Yet it stays, and even better: it is eminently political – and even more so at a time when the idea of “protecting nature” is pressing. In this article, we attempt to unravel its mysteries, tracing its origin, its evolution and the succession of issues in which it has found itself in a central position. The aim is to identify the different realities it embraces, and the particular ways in which we relate to them in the era of global crises.

1. How do we define “nature”?

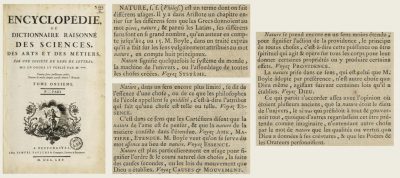

Even today, specialized encyclopaedias still seem to carefully avoid the concept of “nature”: this is for example the notable case of the Oxford Dictionary of Science (2005), but also of the Encyclopedia of environmental ethics and philosophy (2008). The Encyclopaedic Dictionary of Ecology and Environmental Sciences gives it three lines that do not say much, and the Dictionary of Ecological Thought (2015), for its part, takes the precaution of specifying its articles (“nature in philosophy”, “ordinary nature”), thus carefully circumventing the idea of nature itself – although this does not prevent its use in many articles. The same observation can be made on philosophers: nature does not stand among the “major notions of philosophy” in the main university textbooks, has never been on the syllabus of any French examination or competition, and one of the few textbooks to deal with it, André Lalande’s Vocabulaire technique et critique de la philosophie (regularly updated since 1902) imitates d’Alembert by recommending rigorous thinkers to avoid the use of this word, which can mean everything and its opposite. Moreover, the term is openly circumvented by many scientists, who prefer better defined and above all measurable hyponyms – because in the modern age there is no science without quantification – such as “biosphere”, “biodiversity”, “biocenosis”, “ecosystems” and other “physicalities” among anthropologists.

Yet the ecological crisis has brought the idea of nature back to the forefront, and the word is now everywhere: this fact shows that it may not mean “nothing”, and that it is not really substitutable either. At a time when nature is said to be “in crisis”, when everyone would like to “protect” or even “act” on it, it is more imperative than ever to have a clear idea of this concept and its ramifications, which is what this article proposes to do [2].

2. Story of a mysterious word

- generation of that which grows;

- the first immanent element from which growth proceeds;

- principle of the first movement for every natural being;

- and the primeval background from which any artificial object is made or comes from.

These four definitions could be roughly summarized as: growth, principle, power and substance. So here we are in the realm of physics – a term that is occasionally coined – and still far from biology and the environment. Greco-Roman nature does not yet designate a set of objects, but rather the dynamics that animate matter, whether living or not (the term is not often used in the Philosopher’s biology books).

It is in fact the Christianisation of Europe that will change the meaning of the word natura. Indeed, in the Christian cosmology (Figure 3), all dynamics can only come from God: it is him alone who creates the world and animates it, he is beyond nature and nothing is beyond him – whereas among the Greeks, the gods were subject to nature, they were still, in their own way, animals, animated by impulses, passions and needs. In the Abrahamic monotheisms, the whole of reality is now only a creation, a set of passive objects conceived and arranged by the demiurge, and from which only Mankind emerges, which is at once part of this creation but is called to transcend it. This hierarchy is an extremely original idea, which does not seem to be present in any other great civilizational basin: Mankind is then no longer completely a part of nature, and all the value of their existence lies in fact beyond nature, in the Kingdom of God. There is therefore no longer natura naturans, the creative principle which is a simple synonym of God, and natura naturata, which is his creation – knowing that the good Christian must despise earthly things [4], since it is through asceticism that one rises to God. The very word nature will thus become scarcely used in the Middle Ages, essentially returning to its etymological use.

3. Diversity of uses of the word

Despite this dislike of the academic world, “nature” remains the 419th most used word in the French language out of the 60,000 words listed in the usual dictionaries. It has undergone a number of one-off fashion effects, both during the Romantic period and with the cultural revolution of the 1960s and 1970s, in particular because of its fundamentally subversive nature, since the opposition between “nature” and “culture” makes it the perfect recourse when it comes to challenging the established order (“return to nature”) – even though “established order” is also precisely one of the meanings of “nature” [6]…

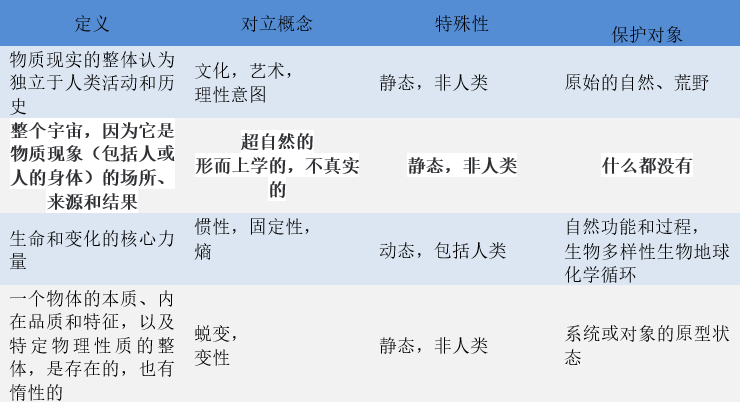

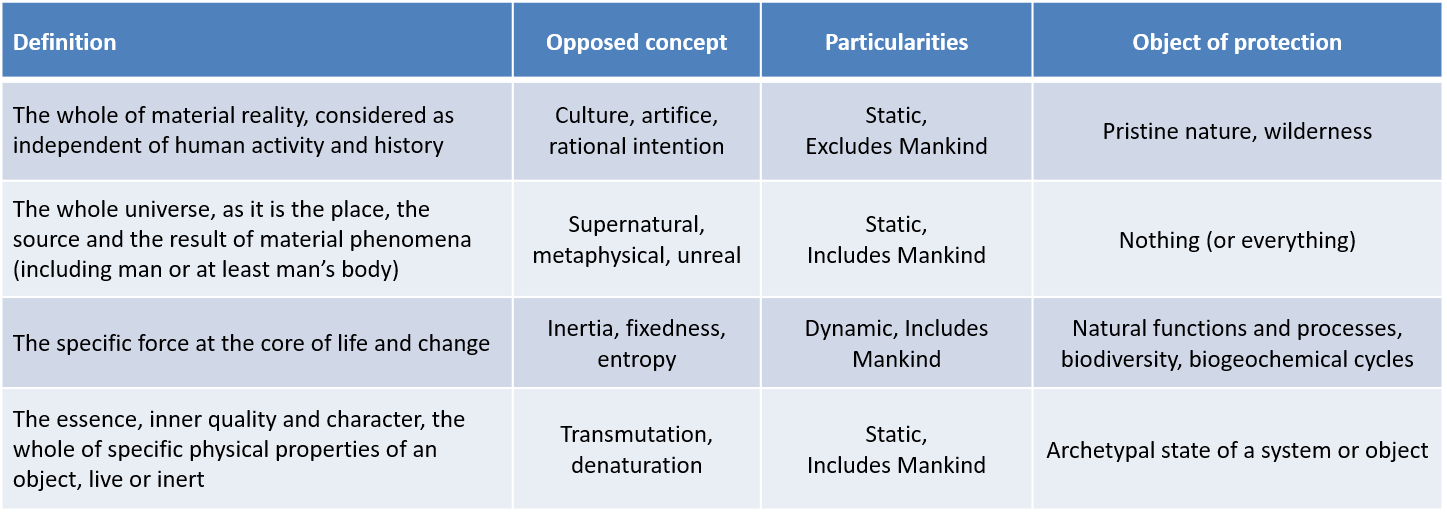

A study published in 2020 [7] attempted to review the meanings and uses of the word “nature”, based on a review of dictionaries, some of which have as many as 20 different and often contradictory definitions. All these ramifications seem to be summarized in four main ideas:

- The totality of material reality that does not result from human will (as opposed to artifice, intention and culture);

- The whole universe as a place, source and result of material phenomena, including man or at least his body (as opposed to the supernatural, the metaphysical or the unreal);

- The force at the principle of life and change (opposing inertia, fixity and entropy [8]);

- The essence, the set of specific physical properties and qualities of an object, living or inert (opposing denaturation).

These four definitions appear extremely heterogeneous in many aspects: some include humans while others explicitly exclude them, and some refer to objects and others to abstract phenomena or characters. They can therefore form the basis for radically different or even contradictory “conservations of nature” , and even, for some, make such an idea absurd: we have grouped these definitions and what they could represent in terms of conservation in Table 1.

4. What to protect?

As we have seen, nature is multiple: it follows that its protection is also crossed by several currents, which have added up rather than succeeded each other over time, at the rate of the emergence of new issues.

4.1. Protecting nature as a set of resources

4.2. Protecting nature as a living environment

4.3. Protecting nature as a set of monuments and landscapes

4.4. Protecting nature as a set of ecosystems

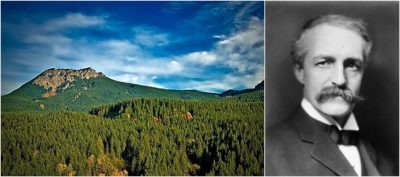

It was not until the emergence of the ecosystem concept in 1935 that the vision of “nature” as a scientific object was renewed, first as a scientific object and then as an object of conservation. While the conservationist tradition was resolutely fixist and attached itself to inert or little changing objects (or at least treated as such), a more dynamic vision of nature was to develop under the impetus of Darwin, and restore the prestige of the third definition we have given. One of the guardian figures of this transition is the famous American forester Aldo Leopold, author of a posthumous work (A Sand County Almanac, 1949) considered as the “bible” of American ecology (Figure 10). Although Leopold was still unfamiliar with the term ecosystem, he nonetheless called for the active conservation of “biotic communities”, later (1992) renamed “biodiversity“. Leopold contributed to the creation of undeveloped forest reserves, protected not for aesthetic or touristic reasons but clearly for their biological and ecological importance, in contrast to the national parks, which until then had been almost all located in arid or mountainous areas.

This new protection of nature seen as a set of ecosystems is therefore based this time on essentially scientific criteria, such as biodiversity, endemism and ecological functionalities – leading to the christening of “ordinary nature” in conservation, since the major functions rely for a large part on the most abundant species [12]. Abstract notions of biological functions, material flows of matter (water, carbon, nitrogen) and energy will also come into play, and their importance for human societies will be embodied in 2005 by the concept of “ecosystem services“, popularized by the Millennium Ecosystems Assessment report commissioned by the UN in 2000. Nature is thus no longer inert and passive, and is becoming a platform for exchanges between biotic communities, of which humanity is one actor among others, powerful but also fragile and dependent.

4.5. Protecting nature as a set of conditions favourable to life as we know it

The scale changed radically at the end of the twentieth century: it was no longer a question of protecting objects, but rather phenomena, on an ever-increasing scale, and finally on a global scale. The very idea of reserve finds its limits here, since these flows and phenomena overflow them largely, and it is therefore the whole organization of human societies that needs to be reviewed, because this protection can no longer be satisfied with a handful of desert or mountainous areas that are sanctuarized because they were unproductive anyway. The climate, the circulation of water and the balance of biodiversity depend less on Yellowstone Park or the Monument Valley than on the use of the fertile soils of the great river plains where all human activities are concentrated, and the artificial separation of nature and humans seems quite illusory [14] (Figure 11).

The new challenge of nature conservation in the 21st century will therefore be to protect nature at the very heart of anthropized spaces, which now largely dominate the planet and, above all, the flows of matter that pass through it – this is what some call the “anthropocene” [15]. In addition to the careful protection of the last remaining unexploited ecosystems, this new nature conservation must also focus on socio-ecosystems, inhabited by a great diversity of human, non-human, living and non-living agents, all of which maintain complex relationships (read: Biodiversity is not a luxury, but a necessity). One of the approaches dealing with this new nature is called “ecology of reconciliation” [16], which aims to make anthropized spaces favourable to biodiversity, through a whole series of techniques and developments. Agriculture must also be rethought so that it no longer forms monospecific deserts saturated with toxic agents, but rather harbors biodiversity that maintains the quality of the soil, the health of the plantations and that of the people who live there [17].

In addition to the technical and administrative challenge, we are therefore witnessing a real philosophical revolution: nature is no longer “outside” Man, and the boundaries between the attention paid to nature and to human populations, hitherto strictly separated in the West between material sciences and human sciences, are fading. This epistemological upheaval is therefore logically accompanied by a new philosophical production, marked in the US by academics such as J. Baird Callicott or in France by authors such as the anthropologist Philippe Descola, the sociologist Bruno Latour, the philosopher Catherine Larrère, grouped together under the label of “environmental humanities“.

5. Messages to remember

- The concept of “nature” is particularly complex to grasp, and has evolved substantially over its history. Even today, four main definitions of nature can be identified, which are extremely heterogeneous and often contradictory; nature would be :

- The totality of material reality that does not result from human will (as opposed to artifice, intention and culture)

- The whole universe as a place, source and result of material phenomena, including man or at least his body (as opposed to the supernatural, metaphysical or unreal)

- The force at the core of life and change (opposing inertia, fixity and entropy)

- The essence, the set of specific physical properties and qualities of an object, living or inert (opposing denaturation).

- The idea of “protecting nature” varies enormously depending on the reference frameworks used, and various traditions of nature protection have developed over time, with distinct, and here too, readily contradictory objects, techniques, concepts and objectives.

- The very vagueness that surrounds the idea of nature prevents its recuperation by a particular disciplinary field (philosophy, biology, politics…) and thus forces the sciences and institutions to confront a popular word rich in varied connotations, conveying many social affects.

- This diversity prevents the idea of technocratization by preserving a diversity of choices and opportunities open to democratic dialogue.

- In this article, only the “Western” concept of nature has been discussed, but its equivalents (or lack of equivalents) in other languages have been the subject of a study published in 2020 [18].

Notes and References

Cover image. [Source: Photo © Frédéric Ducarme]

[1] We will not discuss this usage here, and refer to the work of Jean Ehrard, notably L’Idée de nature en France dans la première moitié du XVIIIe siècle, Paris: Albin Michel, 1963, or to Franck Burbage’s Nature opuscule in the “corpus” collection by Garner Flammarion (2013).

[2] This article is largely inspired by the author’s doctoral thesis, defended at the Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle in 2016, and by two publications that have come out of it: Ducarme F, Couvet D. (2020) What does “nature” mean? Nature Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 6(14):1-8. DOI:10.1057/s41599-020-0390-y ; Ducarme F, Flipo, F., Couvet D. (2020) How the diversity of human concepts of nature affects conservation of biodiversity, Conservation Biology, 34(5), DOI: 10.1111/cobi.13639.

[3] Aristotle, Metaphysics, Delta 4, 1014b.

[4] Matthew 6:19.

[5] Hadot P. Le Voile d’Isis. Paris: Gallimard, Folio essais; 2004. 515 p.

[6] On the (mis)uses of the idea of nature in a moral context, the work of reference is undoubtedly John Stuart Mill, “On Nature”, in Three Essays on Religion. London: Longman Green; 1874.

[7] Ducarme F, Couvet D. (2020) What does “nature” mean? Nature Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 6(14):1-8. DOI:10.1057/s41599-020-0390-y

[8] Beware, here the notion of entropy is taken not in the sense that it has in astrophysics but in its popular sense and on an extremely small scale, that of the energy that tends to dissipate or of the ecosystem that tends to be impoverished.

[9] Ducarme F. (2020), “Evolution et transmutations de l’objet ‘nature’ dans l’histoire de sa conservation”, colloquium De la réserve intégrale à la nature ordinaire, les figures changeantes de la protection de la nature, AHPNE/Archives Nationales, Paris, 29-30 September 2020.

[10] On the concept of “wilderness“, theorized by Roderick Nash (Nash R., Wilderness and the American Mind. New Haven: Yale University Press; 1967), see in particular the numerous works of J. Baird Callicott (such as Callicott JB, Nelson MP, eds., The Great New Wilderness Debate. University of Georgia Press; 1998. 697 p.).

[11] Luigi Piccioni (2014), “Les instruments conceptuels de la patrimonialisation du paysage et de la nature dans l’Europe de la Belle Époque”, “Projets de paysage”, dossier thématique “Paysage(s) et Patrimoine(s): connaissance, protection, gestion et valorisation”, https://journals.openedition.org/paysage/11109.

[12] On this expression, see the works of Catherine Larrère or Rémi Beau, such as Beau R., “Nature ordinaire” in Bourg D, Papaux A, Dictionnaire de la pensée écologique. Paris: PUF; 2015.

[13] Millennium Ecosystems Assessment. Ecosystems and human well-being. Washington DC: World Resources Institute; 2005.

[14] Phalan B, Onial M, Balmford A, Green RE. Reconciling food production and biodiversity conservation: land sharing and land sparing compared. Science. 2011; 333(September):1289-91.

[15] Lewis SL, Maslin MA. Defining the Anthropocene. Nature 2015; 519(7542):171-80.

[16] Rosenzweig ML. Win-Win Ecology. How the Earth’s Species Can Survive in the Midst of Human Enterprise. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2003. For a summary in French, see Couvet D, Ducarme F. L’écologie de la réconciliation, du défi biologique au défi social. Journal of Ethnoecology. 2014;6:13.

[17] Butler SJSJ, Vickery JAJA, Norris K. Farmland biodiversity and the footprint of agriculture. Science, 2007; 315:381-4.

[18] Ducarme, F., Flipo, F. and Couvet, D. (2020), “How the diversity of human concepts of nature affects conservation of biodiversity” Conservation Biology 34:6, doi:10.1111/cobi.13639

The Encyclopedia of the Environment by the Association des Encyclopédies de l'Environnement et de l'Énergie (www.a3e.fr), contractually linked to the University of Grenoble Alpes and Grenoble INP, and sponsored by the French Academy of Sciences.

To cite this article: DUCARME Frédéric (March 1, 2021), What is nature?, Encyclopedia of the Environment, Accessed September 18, 2024 [online ISSN 2555-0950] url : https://www.encyclopedie-environnement.org/en/life/what-is-nature/.

The articles in the Encyclopedia of the Environment are made available under the terms of the Creative Commons BY-NC-SA license, which authorizes reproduction subject to: citing the source, not making commercial use of them, sharing identical initial conditions, reproducing at each reuse or distribution the mention of this Creative Commons BY-NC-SA license.