『

■2020

■A4

■カラー160

■

■

https://shop.kogei-seika.jp/products/detail.php?product_id=393

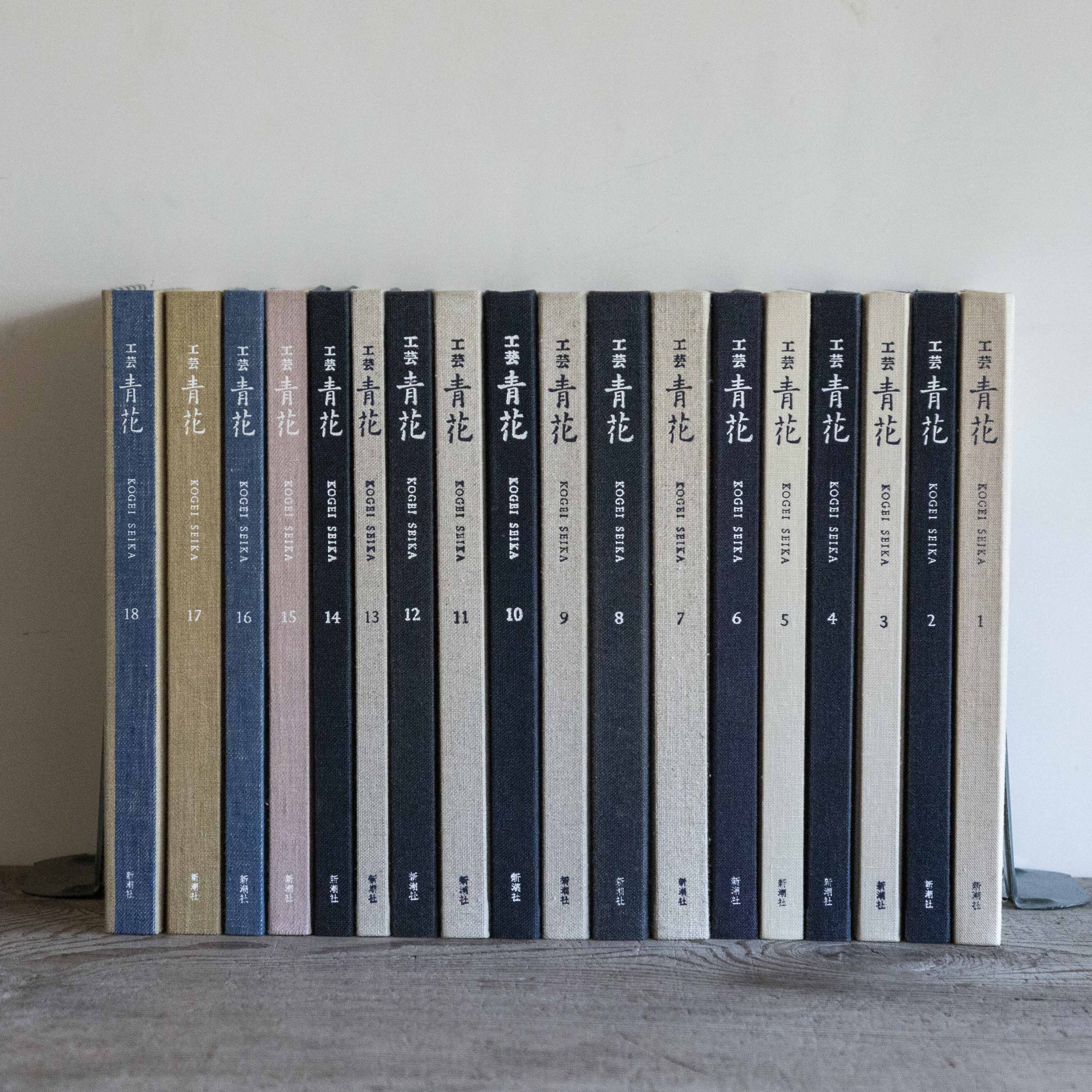

Kogei Seika vol.14

■Published in 2020 by Shinchosha, Tokyo

■A4 in size, linen cloth coverd book with endpaper made of Japanese paper (kozo)

■160 Colour Plates, Frontispiece with a stencil dyed art work by Michiaki Mochizuki

■Each chapter is accompanied by an English summary and all photographs are with captions in English

■Limited edition of 1000

■10,000 yen (excluding tax)

■To purchase please click

https://shop.kogei-seika.jp/products/detail.php?product_id=393

1

The Craft in Beijing

・

・

・「

・

・

2

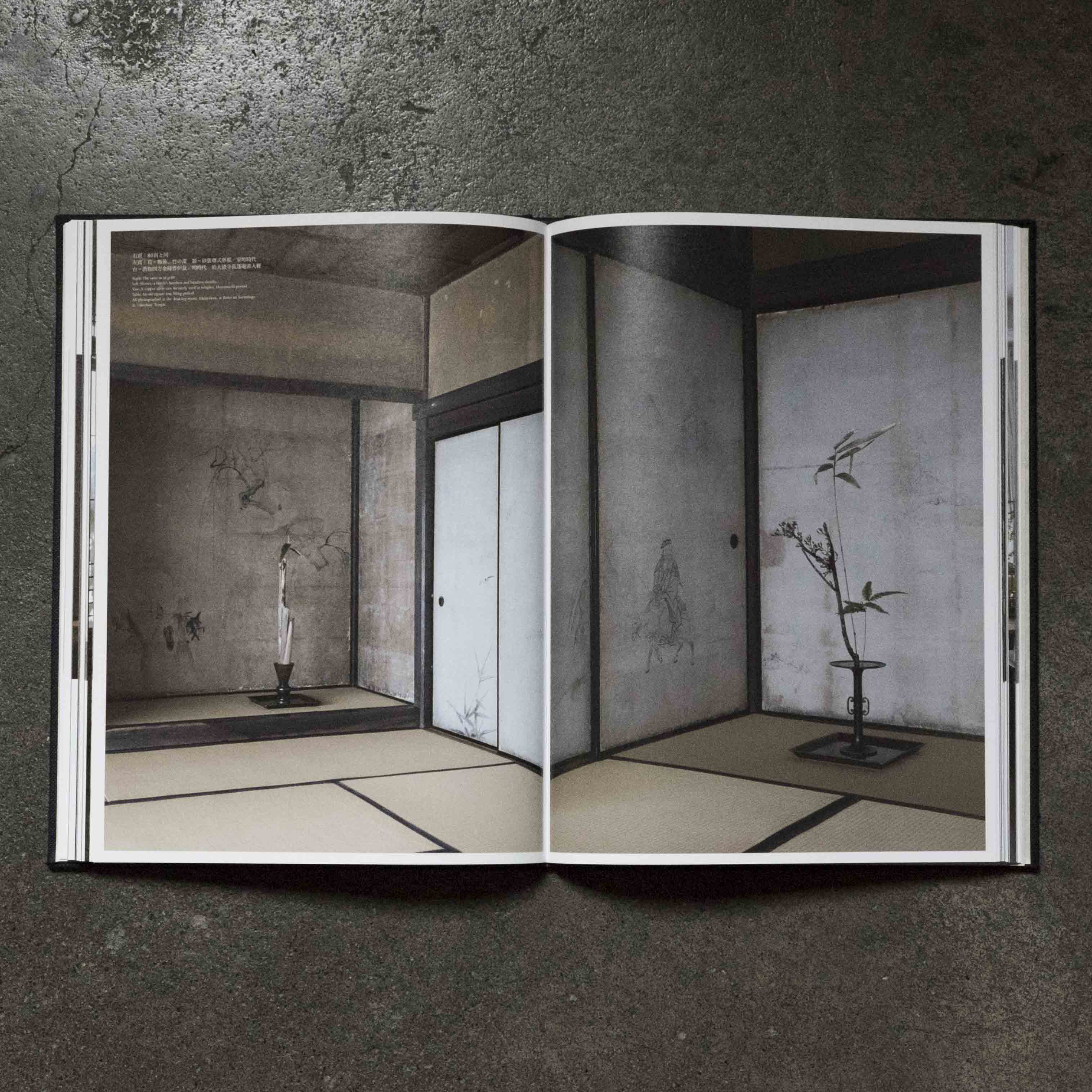

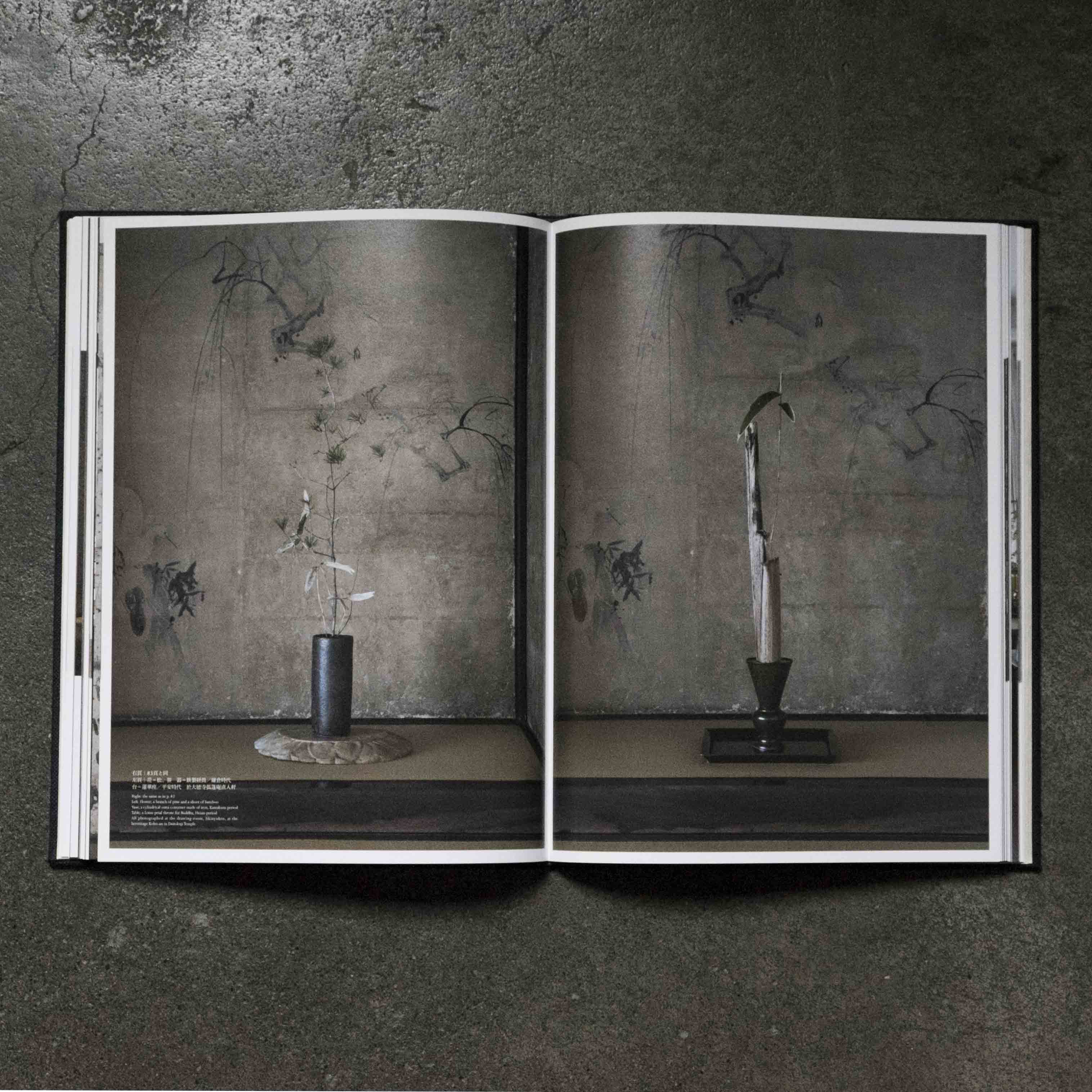

Flowers by Toshiro Kawase at Koho-an, Daitokuji Temple in Kyoto

・シンをたてる

3 メキシコのブリキ

Mexican Retablos from Keisuke Serizawa Collection

・

・

・ロベール・クートラスをめぐる

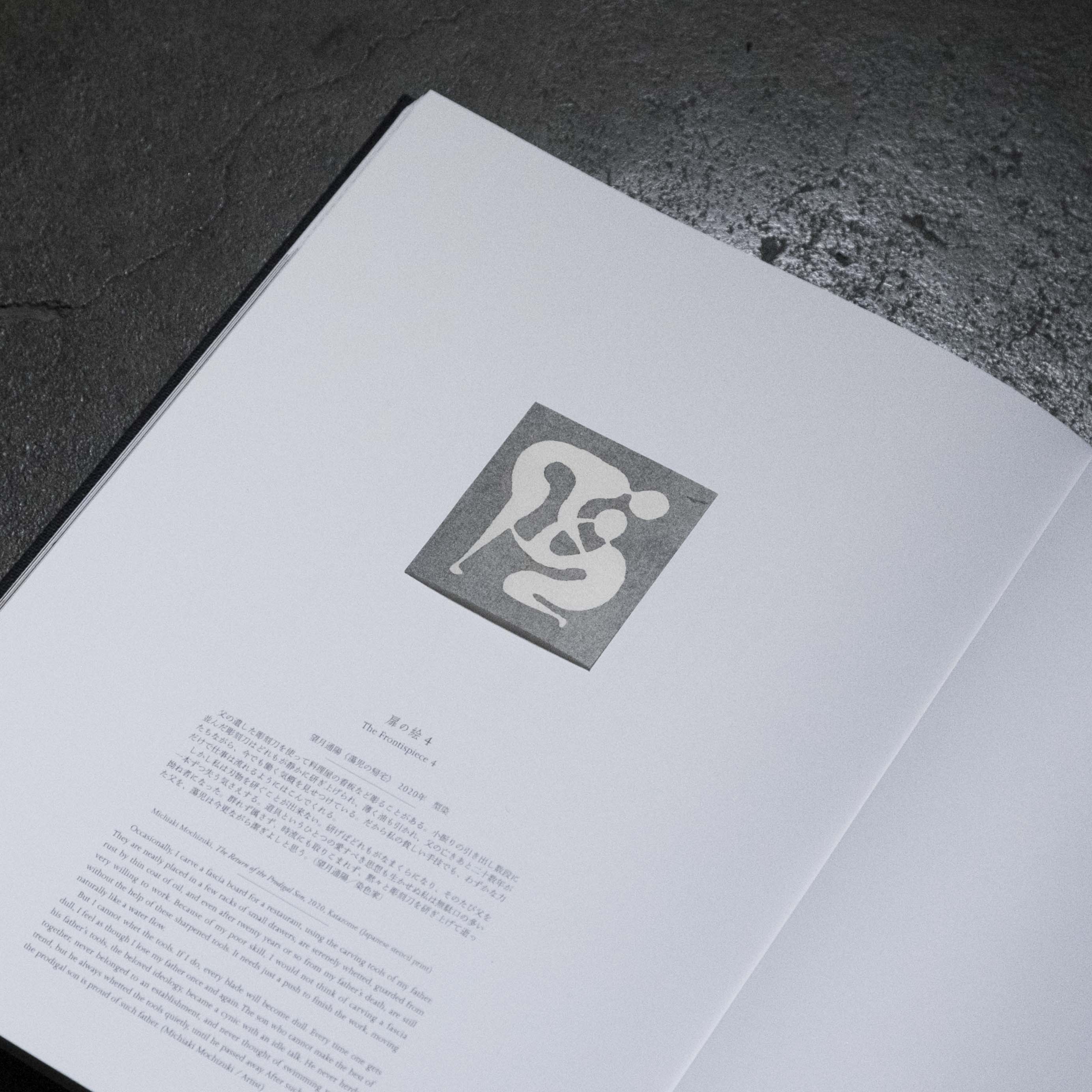

The Frontispiece 4

しかし

Michiaki Mochizuki, The Return of the Prodigal Son, 2020, Katazome (Japanese stencil print)

Occasionally, I carve a fascia board for a restaurant, using the carving tools of my father. They are neatly placed in a few racks of small drawers, are serenely whetted, guarded from rust by thin coat of oil, and even after twenty years or so from my father’s death, are still very willing to work. Because of my poor skill, I would not think of carving a fascia without the help of these sharpened tools. It needs just a push to finish the work, moving naturally like a water flow.

But I cannot whet the tools. If I do, every blade will become dull. Every time one gets dull, I feel as though I lose my father once and again. The son who cannot make the best of his father’s tools, the beloved ideology, became a cynic with an idle talk. He never herded together, never belonged to an establishment, and never thought of swimming with the trend, but he always whetted the tools quietly, until he passed away. After such a long time, the prodigal son is proud of such father. (Michiaki Mochizuki / Artist)

1|

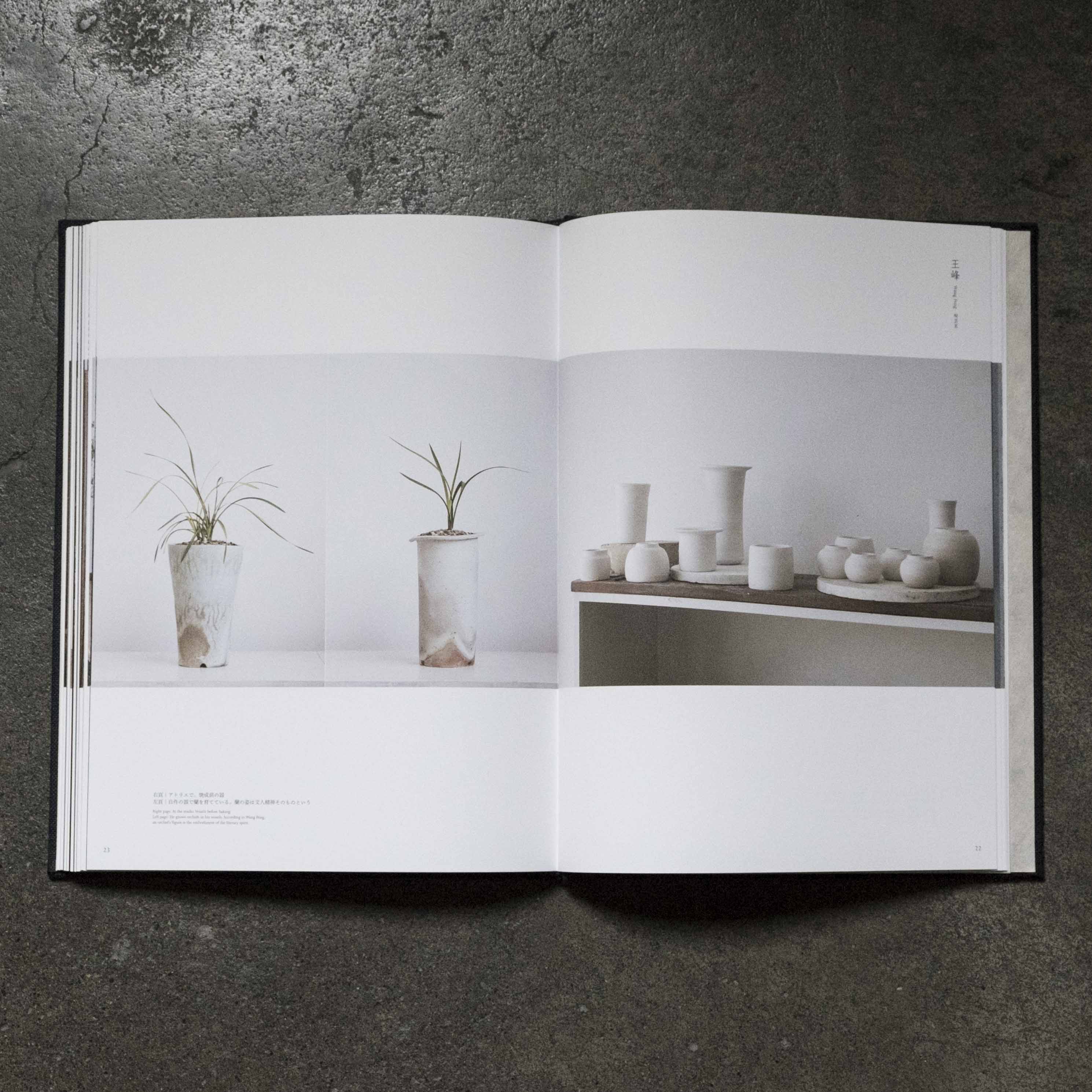

The Craft in Beijing

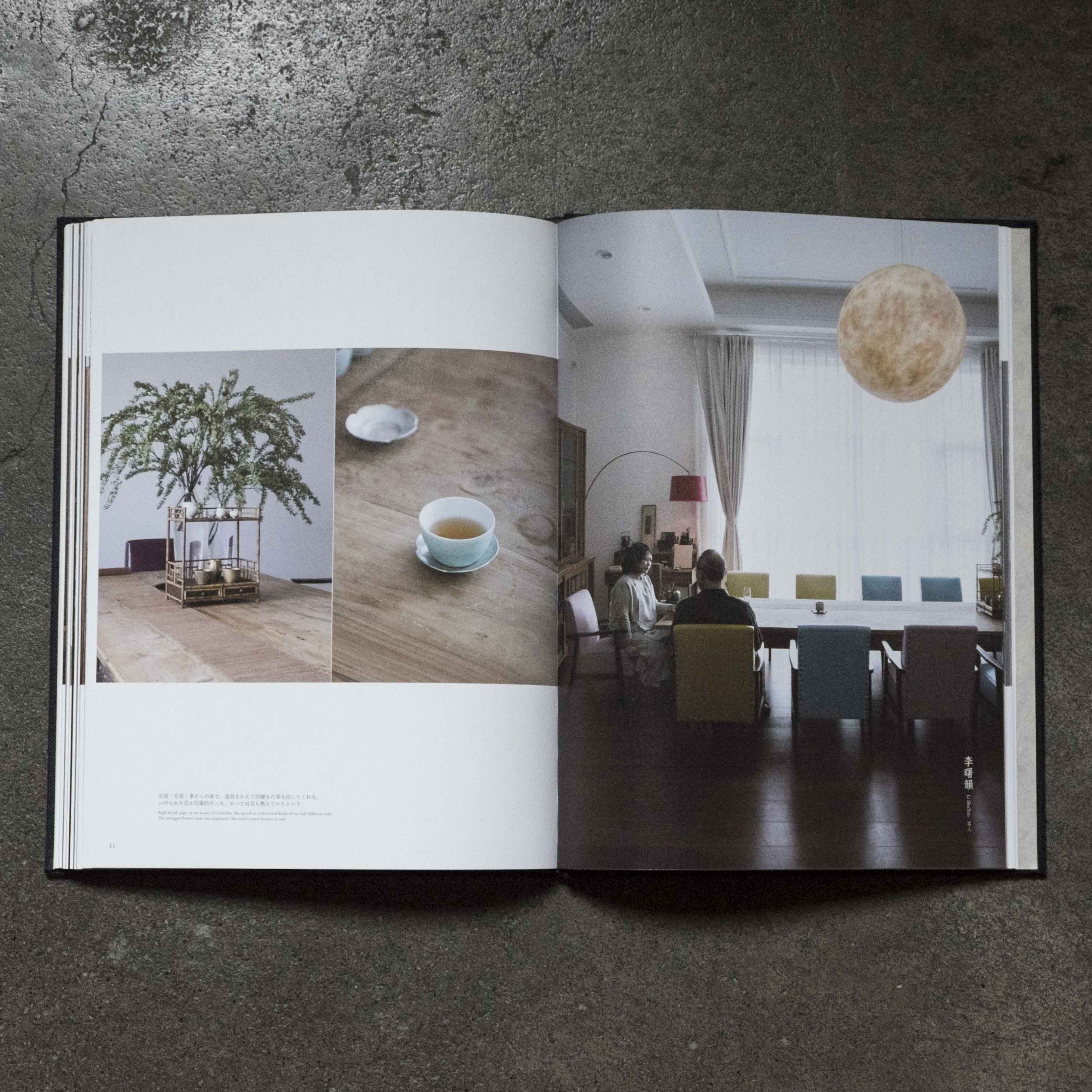

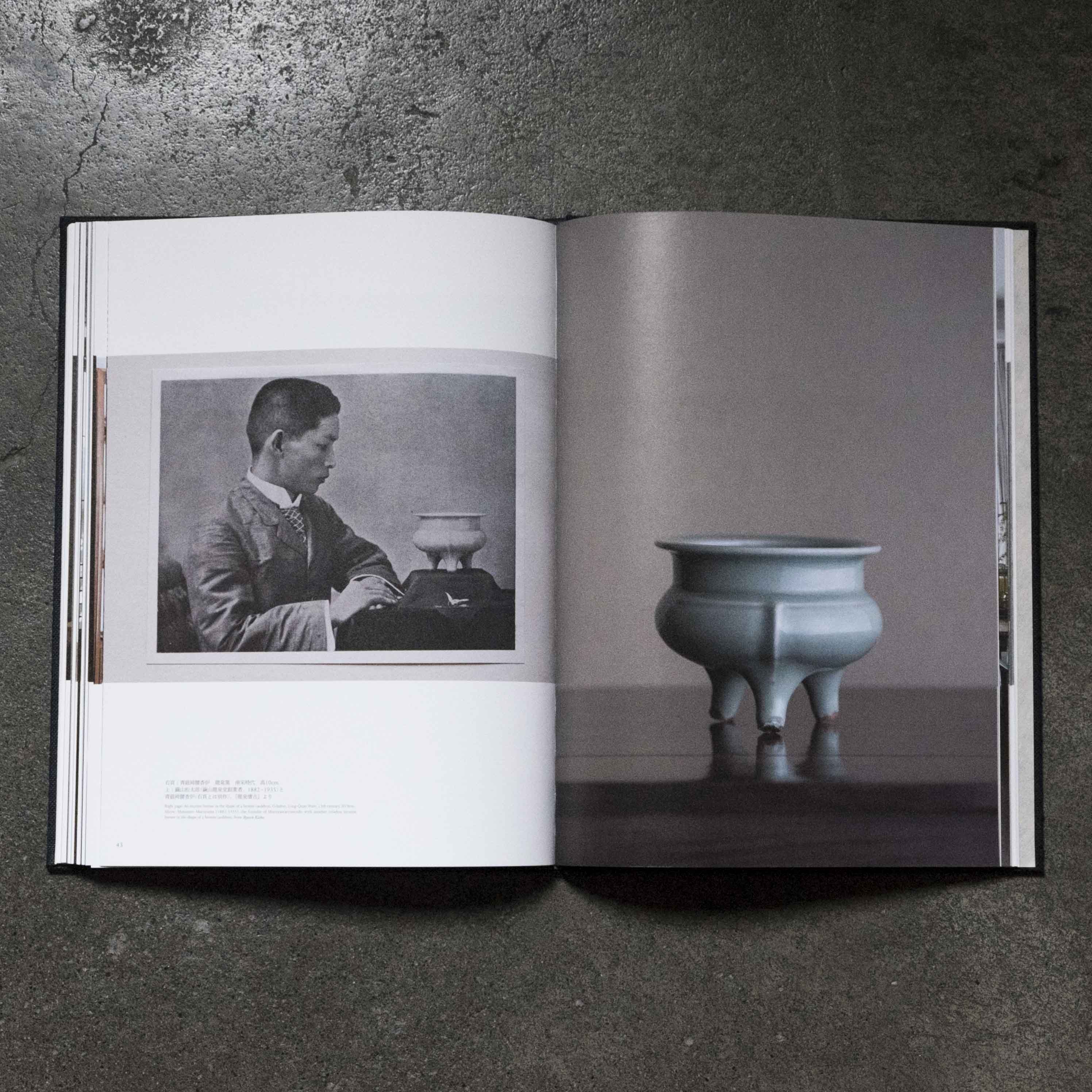

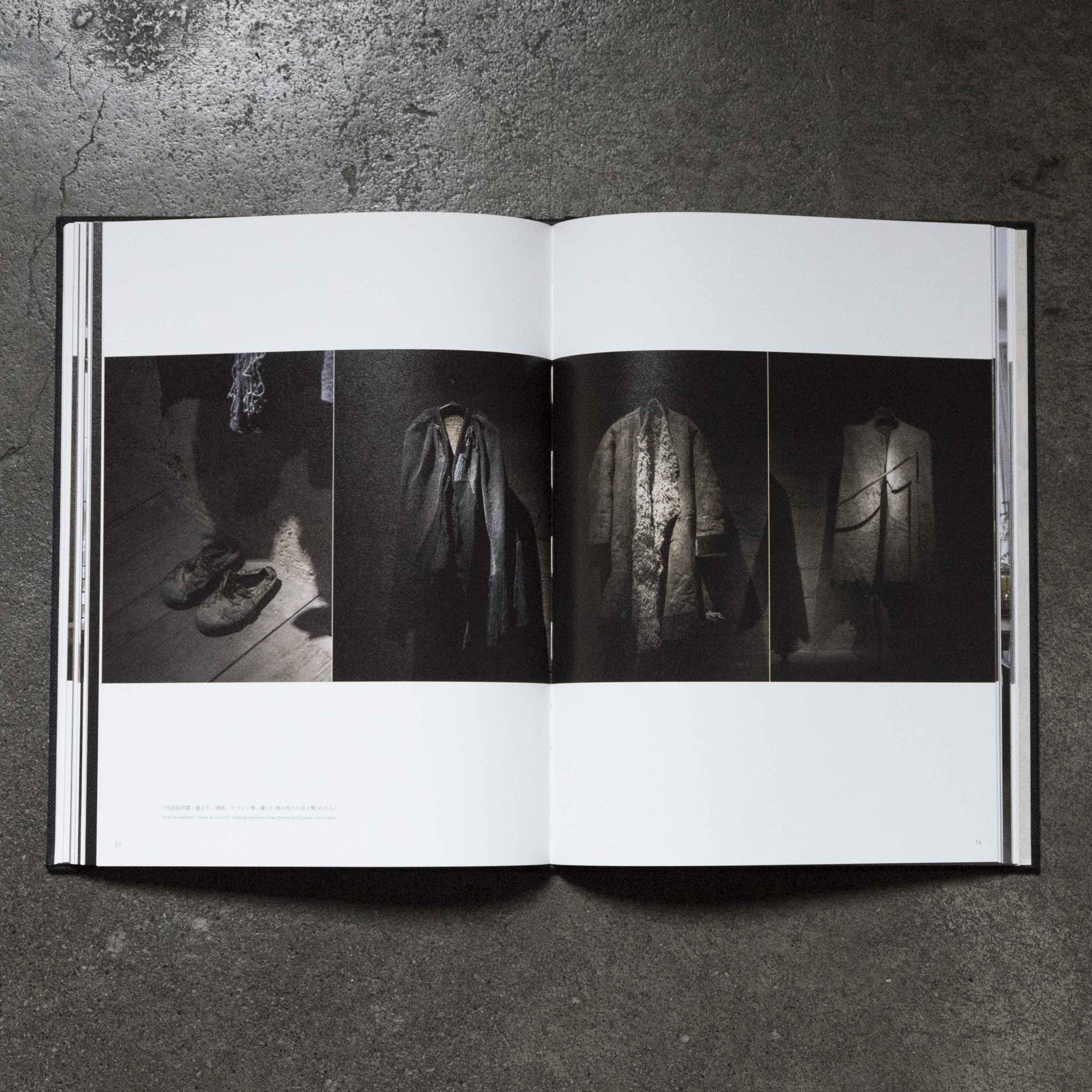

Last April, I visited Beijing with Masanobu Ando (born in 1957), a ceramic artist and an owner of Galerie Momogusa, in Gifu. The theme was the craft, and the object was the person. In recent years, not only in Beijing but also in East Asia, the so-called ‘Craft for daily life’ culture of Japan has been gaining broad acceptance. As a representative artist, Ando frequently holds solo exhibitions and tea parties (Chinese tea) in China.

Ando chose whom to see. We met many, but I chose seven for this article. Huang YongSong (an editor, born in 1943), Wang Feng (a ceramist, born in 1972), Li ShuYun (Chinese tea master, born in 1969), Bai YunZe (an antique dealer, born in 1988), Xu Mo (a metalwork artist, born in 1968), Li RuoFan (an owner of the craft shop, born in 1972), and Ma Ke (a fashion designer, born in 1971) is the seven. Surprisingly, not one of them was born in Beijing. What I felt very strongly as we talked was that these people’s strength lies in their feet. For example, their spiritual foundation is the philosophy of LaoZi and ZhuangZi, the teachings of Confucius and Mencius, and the literary culture of Tang, Song, and Ming dynasty. Such continuity and indigenousness should have been present in Japanese culture in the past (perhaps in a different way to China), but it was quickly overtaken after the WW2. Is there a substitute for it?

The ‘Craft for daily life’, said to have begun in the 1990s, was a cultural movement that attempted to place ‘daily life’ at its core. One of the things I noticed in Beijing was that ‘literati’ are not (or seemed to be) the ‘a kind of ‘Art’-ification of daily life’ based on a spirit of resistance. We are not far away. (S)

2|

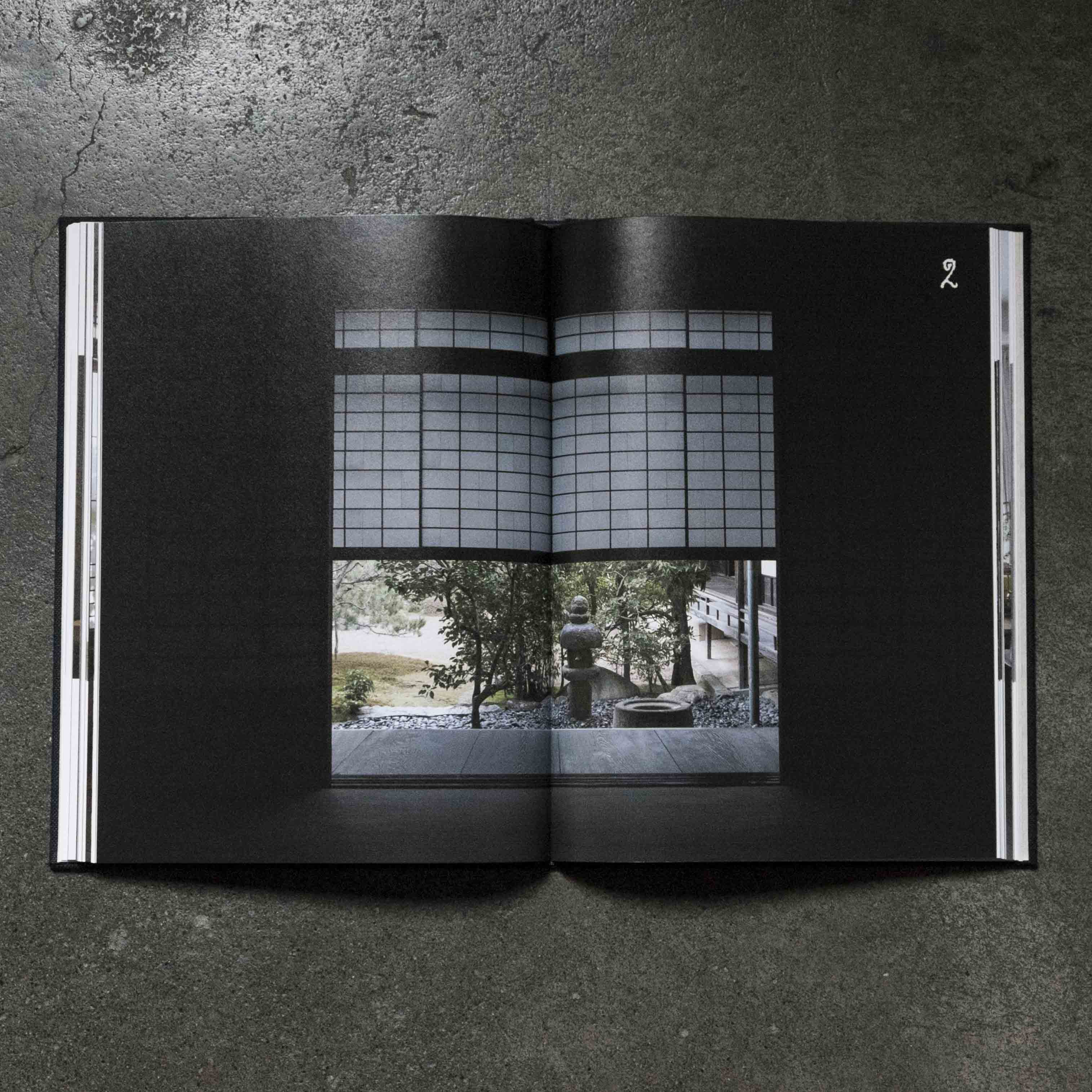

Flowers by Toshiro Kawase at Koho-an, Daitokuji Temple in Kyoto

たてはなとは

たてはなとはなにかという

The flowers of Toshiro Kawase (Ikebana artist, born in 1948) were arranged as Tatehana in the hermitage Koho-an in Daitokuji Temple in Kyoto.

Tatehana (the vertical flower arrangement) is a style that was established in the Muromachi-period and is the origin of Ikebana as an art form. Purify the branch of an evergreen tree cut from the mountains, select rice straw, pull out the core of the mugwort and bundle it as a peg. Put it in a vase and fill it with water. You must correct attitude, calm your mind, discern the heavens and the earth, and then, raise the branch vertically with both hands and push it in the middle of the peg with all the might as if to thrust it to the root of the earth. Then ‘Kami’, a god will appear from the vase, and the straight evergreen branch will become the core (‘Shin’). By Toshiro Kawase.

The question of what is a Tatehana is a lifelong question for Kawase, as is the flower of Nageire (throwing in style). (His book, To arrange Tatehana, coming up later this year, is going to be a compilation of his concept of Tatehana, which is an expanded version of the articles he wrote in Geijutsu Shincho over the six years.

‘To make a tree, a grass, and a flower into an arrangement is like making a portrait of Kami. To build the core (‘Shin’) is different from the act of arrangement and throw in and it has a special holiness to it because the action of verticality is the embodiment of ancient ritual of venerating Kami the god. It is not a few seconds in time, but at this moment, I return to the primordial beginning.’

Koho-an within Daitokuji Temple of Zen Buddhism is a hermitage which Kobori Enshu (1579-1647) relocated and expanded from Ryuko Temple in 1643. After the fire in 1793, within a few years, it was rebuilt with the efforts of Matsudaira Fumai (1751-1818) and others. The teahouse Bosen was faithfully reconstructed from the three-dimensional plan of the original building. The drawing-room Jikinyuken is a little different from the original. The teahouse Sanunjo was attached to Jikinyuken. (S)

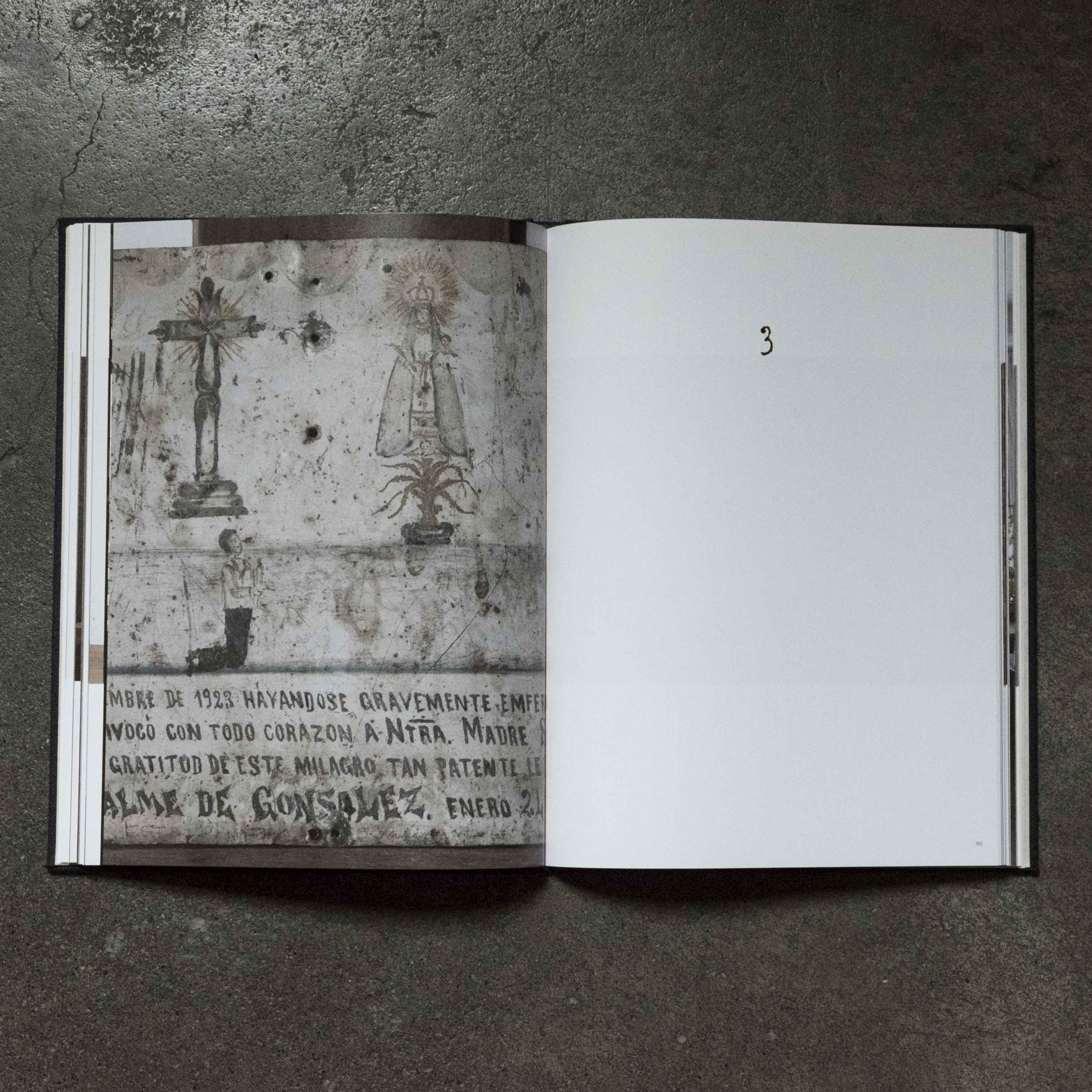

3|メキシコのブリキ

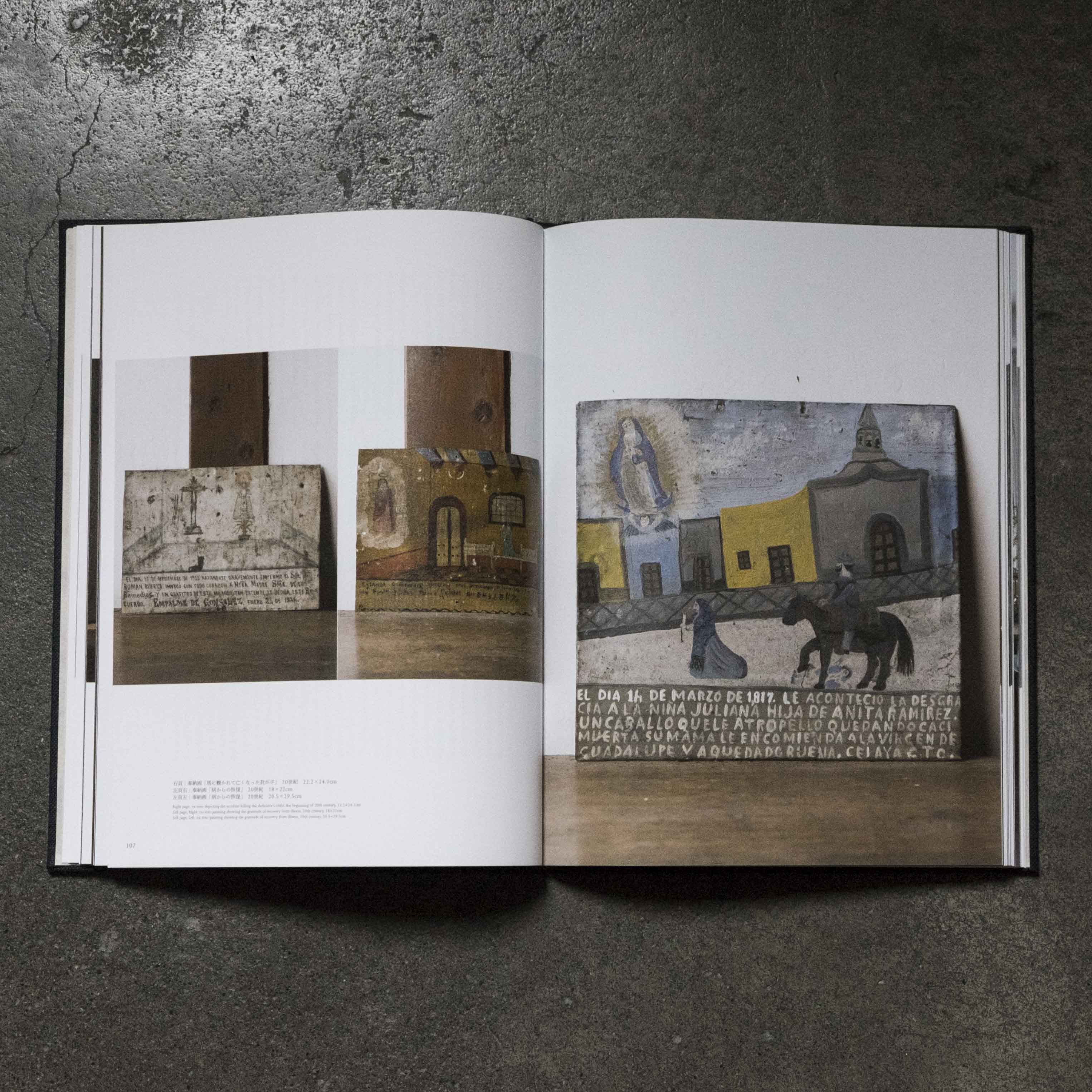

Mexican Retablos from Keisuke Serizawa Collection

〈メキシコを

メキシコのブリキ

Perhaps because Mexico is a country where crafts are still alive, people involved in the Mingei movement (Craft movement in Japan) was fond of the country. Many, such as Sanshiro Ikeda, own tinplate paintings from Mexico. Among them, Keisuke Serizawa has a particular preference for tinplate paintings, and to my knowledge, and was the largest collector of Mexican tinplate paintings in Japan. By Takao Takaki.

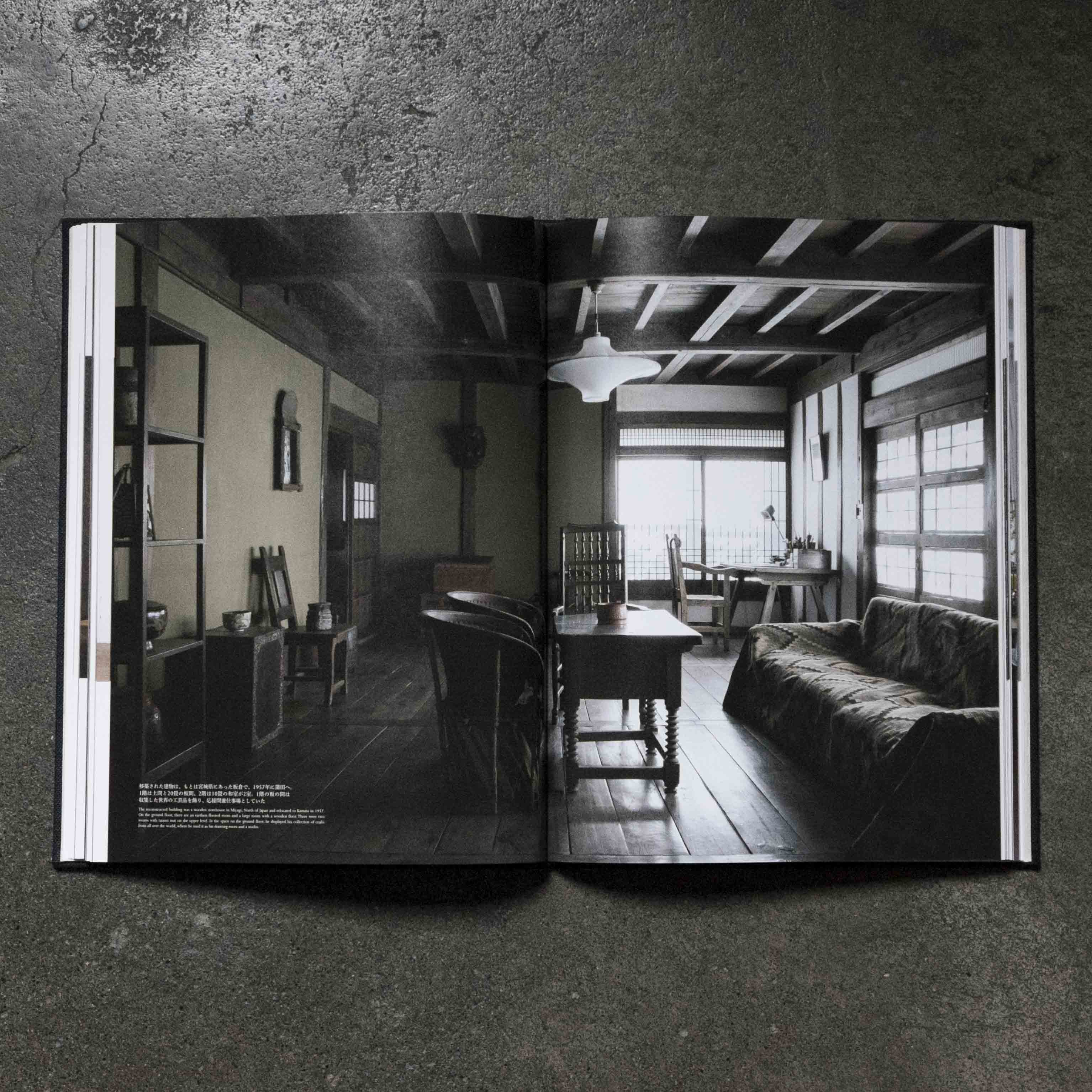

Keisuke Serizawa (1895-1984), was a textile-dyeing artist, born in Shizuoka Prefecture. After graduating from the Design Department of the Tokyo High School of Technology, learned about Okinawan red stencils with Muneyoshi Yanagi (1889-1961), and proceeded on the path of craft and stencil dyeing. A summary of the work can be seen at the Shizuoka City Serizawa Keisuke Art Museum, designed by a Japanese architect, Seiichi Shirai. Serizawa collected crafts from all over the world, and the museum houses and displays about 4500 from his collection. Kazumi Sakata of the Antique Sakata reminisces about the day when he brought Ethiopian crosses and other items to the Serizawa residence. ‘I was happy on the way home. I made up my mind to make him an aim and collect items that would make him gasp ooh and aah,’ writes Sakata in his book, My Own Yardstick (2003).

In the second issue of Kogei Seika (2015), we featured tinplate paintings from Mexico. The article was on Takaki’s ex-voto collection. He writes that ‘I call these ex-voto paintings as ‘tinplate paintings’ after Keisuke Serizawa, but in Mexico, there are two different categories, i.e., the painted ex-voto and retablo. (…) The saints must be there on painted ex-voto, for the miracles (mostly trivial and sometimes significant) explained with the words and depictions in detail are realized by their intercession.’ ‘The tinplates are not the only media used for ex-voto. Fabric, wood, or plywood is also appropriate. The artisans in the church and those in the printing business of the neighbourhood initially undertook painting the ex-votos. The profession as ex-voto painters only established later in history.’

In this issue, we photographed all eighteen of Serizawa’s tinplate paintings in the old residence, which was relocated from Kamata in Tokyo to Shizuoka. (S)