2. Towards an Effective and Efficient Public Sector Pay System in Israel

This chapter examines the components of an effective public sector pay system and recommends changes to Israel’s public sector pay strategy. The chapter begins with an assessment of the relative pay gap between the public and private sector, and follows with an analysis of the job classification system – the foundational architecture of the pay system. The chapter then looks at the specifics of the pay system, how pay is structured and able to attract and retain different skill sets. It considers how Israel’s pay system could be better used to motivate and reward performance through performance pay, promotion and mobility.

This chapter addresses the need to design a transparent, effective and efficient pay system in order to equip the Israeli public sector for the future of work. Emerging technologies and changing societies are giving rise to new competences and skill sets to address complex policy problems. Public sector employment and remuneration policies and tools need to keep pace. The OECD has been conducting studies on the future of work in the public service. As a large employer, Governments are adapting their public employment systems to meet challenges of digitalisation, and remain attractive employers for increasingly diverse groups of highly skilled workers. The OECD has summarised these preparations under the following three themes, each with its own implications for pay systems:

Forward looking: public service employers will need to be better at foreseeing the changes on the horizon and recruiting skills and talent that can adapt. This requires job classification systems that can adequately incorporate emerging skills and attract them with appropriate remuneration packages. It also requires up-skilling and re-skilling to ensure that existing employees are equipped with skills needed to address current and future public sector challenges.

Flexible: public services will need to be flexible and agile to respond to unforeseen change. This implies the need to redeploy skills to emerging challenges and pull together multi-disciplinary teams across ministries and agencies. Pay systems therefor need to strike a careful balance between specificity for skills and talent, and standardisation across organisations to enable mobility and agility.

Fulfilling: the diversity of the public service workforce will continue to grow to incorporate more skills and backgrounds. And with diversity of people comes the need for a diversity of employment models and individualisation of people management. This suggests the need to think about pay systems that recognise and reward motivation and achievements, without crowding out intrinsic motivation of public employees.

The government response to the Covid-19 pandemic illustrated the importance of these three factors in addressing modern policy challenges, in particular flexibility. The ability of governments to react to the pandemic largely depended on the degree to which organisational structures and processes were able to adapt to the new and fast-changing conditions. Flexible and fit-for-purpose pay systems are an important component of that change: they enable governments to attract, recruit and reallocate needed skill sets.

Pay systems need to be a fundamental part of a future-oriented public service strategy. The strategy would ideally consider the emerging needs of the public service workforce, and pay would be aligned to support these needs. While pay is not the only reason that people apply for or leave jobs, it is an important factor. However pay in many public service systems is the result of the past, rather than focused on the future. Pay systems were often designed in and for a very different era. Adjustments since then have tended to be at the margins. This is likely due to two main points. First, pay systems need to be stable and predictable, since they form the basis of long careers. This makes large scale change very challenging to do effectively. Secondly, the heavily unionised environments of many public employers requires change to happen through collective bargaining and the many vested interests make it challenging to come to agreements. The last major cross-sectoral pay reform in Israel revised the defined benefits pension plan in 2002. Since then, no other major pay reform has succeeded. Important reforms to the public sector pay system are made difficult by the lack of social and political consensus.

Central governments need to engage and retain effective and skilled employees. Pay is a key component of that, particularly in a context where candidates with highly sought-after skills have options outside the public sector to work for the public good. Assuming equal conditions around working hours, location and employment conditions, a difference between the pay in the public sector and the one in the private sector, i.e. the pay gap, would be an indicator of the relative attractiveness of sectors.

Since 2008, most OECD member countries faced fiscal pressures that resulted in pay freezes or cuts. In Israel, however, pay negotiations resulted in an increase of pay in the public sector compared to the private: in the last 10 years, pay per employee in the public sector increased by 25% in real terms whereas the increase in the private sector was 11% (Israel Ministry of Finance, 2017). Hence, in recent years the average relative attractiveness of the public sector has increased.

Despite this, the estimates of the pay gap in Israel seem to fit into the global picture of pay gaps in other OECD member countries (see Box 2.1). The average pay in the public sector is higher but this statistical effect usually disappears or even becomes negative when controlled for experience, education or position. The average pay gap is mainly explained by the structural effect; employees are more skilled on average hence higher paid in the public sector.

As such, the primary concern for Israel is not closing the overall ‘gap’ between the public and private sector: given the relatively small difference in pay, the focus instead should be on targeting pay adjustment for certain professions where there is a marked gap with the relevant market level (e.g. civil engineers), without impacting the overall budget envelope. This is supported by the findings of a recent study conducted by the Bank of Israel which finds that the return on skills is higher in the private sector than in the public sector (Mazar, 2018[1]). This suggests that public sector pay does not compensate workers for their skills in a competitive way compared to the private sector, and a shortage of skilled employees can be expected, everything else being equal.

Pay gaps for specific skills in Israel’s public sector

Wages become inconsistent with the competencies one needs to attract if the pay structure does not adapt to social and technological change. In Israel, there seems to be inconsistency for specific job positions. When compared to the private sector, the public sector in Israel pays sometimes more and sometimes less, depending on various factors. Hence, the relative attractiveness of job positions in the public sector varies: for instance, the public sector pays less for new competencies (engineers, digital competencies) and on the contrary, more for lawyers or low skilled administrative workers.

A compressed pay scale (relatively higher pay for low-skill/junior positions, and lower pay for high-skill/senior positions) is common in many public sectors. This impacts the relative attractiveness of the public sector, and lower positions can be very attractive while senior positions much less so. The jobs that are likely to disappear or be transformed in the future are those whose main tasks are simple and routine, where robots and automation can dramatically be efficient substitutes (OECD, 2018[2]). Hence, there is a need to remain attractive for jobs where there are more non-routine tasks and/or which require understanding human actions and reactions in social contexts. These higher-value skill sets are also increasingly in demand in the private sector, which makes it necessary to adapt pay and differentiate it effectively. This is the core challenge of a strategic reform to pay for the future of work.

Moreover, differences can arise between specific employees and at a specific age or specific positions. For instance, compared to the private sector, the public sector pays more for administrative employees but less for public engineers (Israel Ministry of Finance, 2018) resulting in attractiveness issues for engineers in the public sector. It is important to stress that this comparison between averages can cover structural differences in gender, locations or working conditions but is a hint to a need to adapt the pay grid to detailed competencies.

Pay is not the only factor that contributes to attractiveness. Other variables also influence employees’ choice of employer, among which are the desire for job security (which may become even more important during economic downturns such as those resulting from the Covid-19 crisis), autonomy at work, sharing common values, serving the public interest, the balance between work and private life, and working conditions. Research from Gallup has pointed to desire for growth and development as a distinct preference for younger candidates (Gallup, 2016[3]) ). The number of days of work, vacation days and the total number of hours worked also directly impact the hourly wage. By improving talent identification and conditions of work, the government could improve attractiveness. One should recall that the pay gap is only one aspect of the advantages and constraints of a job and that working conditions and institutional rules are to be taken into account to assess the full premium or penalty.

There are three main challenges to quantifying the pay gap in the public sector. First, it can prove difficult to compare occupations, such as how judges are paid relative to police officers. Second, the definition of pay itself can be problematic, as social security and pensions may differ radically in the public and private sectors. For example, in Israel older public sector employees receive a defined benefits pension plan, which is more favourable than pensions in the private sector

Besides methodological issues, one should be cautious when interpreting the pay gap. One could deduce from a pay gap that there is room for pay freeze or cuts. However, institutional settings affect the spread of wages. For instance, a minimum wage compresses wages at the bottom of the distribution in the private sector. This affects the average gap between the public and the private sector. Moreover, the public employer is expected to behave according to the values of fairness and non-discriminatory practices. For instance, if the average wage is higher in the public sector this could be mostly driven by less discriminatory pay practice whereby there are opportunities for women to earn a similar return for their investment in education and experience as men.

Despite the challenges listed above, the economic literature estimating this pay gap is abundant. Most studies point to a more compressed structure of pay in the public sector than in the private sector, (e.g Grimshaw et al. (2012) on five countries studied: France, Germany, the United Kingdom, Hungary, and Sweden). Pay premium (higher pay in the public sector) substantially reduces and becomes insignificant when composition differences between both sectors’ workforce are controlled for. In France, the estimate of the premium, when controlled for various variables, is around between 7% and 15% for women but is insignificant for men. In Germany, there is a premium for female public sector employees between 8% and 19% but no premium for men. In Sweden, there seems to be no significant pay gap. In the United Kingdom, the premium is between 9% and 18% for female workers but not significant for men. When controlled for skill, the pay gap results in a pay penalty for high skilled workers in those countries, and in a premium for low skilled workers. In Greece, Ireland, Italy, Portugal, and Spain pay premium seems to be higher than in other European countries

Some studies even point to the fact that the analysis of the pay gap should take into account the risk of unemployment and the evolution of pay along with the whole career. (Postel-Vinay and Turon, 2007[4])estimate that the wage gap in the United Kingdom is reduced to 0% for individuals with a low risk of unemployment when the whole career is taken into account (including pensions), because of the different wage profiles and different rates of unemployment between the two sectors. Dickons et al. (2012) extend the study on the United Kingdom and analyze earnings profiles along the career in 5 European countries – Germany, The Netherlands, France, Italy and Spain. They insist on the fact that public-private differences in pay are due to the selection of heterogeneous employees into public and private sectors. The pay gap would result of the fact that the public sector selects heterogeneous individuals: according to these studies, the public sector doesn’t pay differently similar employees but hires different employees and hence pays them differently.

In conclusion, some specific positions appear to be relatively overpaid and others underpaid compared to the private sector. Hence, a general wage increase or decrease would be ineffective from a strategic perspective. A selective increase in pay would help attract and retain desired profession. Moreover, an update of the job classification, which underpins the pay system, may be needed to better target pay adjustments to specific job positions and competencies.

Revising job classifications is an important step in designing any new pay system. Job classifications distinguish and group jobs, positions, grades and eventually pay ranges. During the hiring process, job descriptions are published to target the specific labour needed. They are also used in promotions, careers, and performance evaluation process. They can be very useful in strategic workforce planning and in identifying training needs.

The design of job classification systems is complex because they must combine flexibility and coherence. A job classification needs to be flexible to fit to the evolving needs of the organisation and the competences available on the job market. However, the classification also needs to be coherent and stable over time. This is because it is a tool for the government to manage promotions, training needs, and implement strategic planning. Moreover, it provides employees with transparency and predictability regarding their pay and career, hence is an important component of attractiveness.

An effective job classification system must find the right level of precision and specification in positions and grades. When too precise, it makes it difficult for managers to adapt a job to changing circumstances, such as the introduction of new tasks, technology or working methods. On the other hand, if too broad, it may not give enough room to differentiate pay according to job characteristics, which may affect employer attractiveness. It may also make it harder to manage career paths. An effective job classification is related to the purpose of use. Hence, the needs of recruiters need to match the job classification system. A one-to-one correspondence between demand and classification has the advantage of precision, transparency, and efficiency in the matching process. However, if the job classification is too narrow, frequent revisions will be needed.

In an economic context where emerging technologies make it necessary to adapt, to learn, to acquire new competencies, end tasks and take in charge new ones, the job classification needs to be rather flexible without threatening employee’s security or working conditions. In most OECD member countries (see Box 2.2 for UK and French example), a civil servant is hired under a particular job classification but expects that the role or the working conditions will evolve. Labour law and general agreements specify the constraints that the employee must comply with, but changes in working conditions or the work environment within those boundaries are possible.

In many OECD member countries, various compensation mechanisms allow changing working conditions. For instance in France, public employees who accept a functional or geographical mobility for at least three year are entitled a compensation or bonus. In the same way when the whole unit has to be re-structured or needs to change location, public employees are also entitled a one-time compensation. The amount of this allowance depends on the family situation, the number of years in the position and the distance between the old and the new location. However, some job positions include geographical mobility hence are not open to that sort of compensation. For instance, teachers or judges have a compulsory job and geographical mobility in their career.

Digital technologies drastically affect the tasks that employees achieve and not simply the position. They are expected to alter what employees do but not the objective or the service they provide. Many OECD member countries have launched this digital revolution in the public sector without necessarily altering the job classification. For instance, the UK launched the Government Technology Innovation Strategy in June 2019 to set out how to use technologies, including AI, in the public sector. It includes a wide program to attract data analysts but also to provide in-house training for public employees. The flexible job classification in the UK allows this functional mobility.

Towards a flexible but consistent job classification system in Israel

The job classification system in Israel is both too specific and too general. Individual job descriptions appear to be extremely detailed leaving no room for modifications that would be considered normal in many countries, such as the rebalancing of work tasks due, for example, to the introduction of new technologies. This requires the public employer to reformulate the job description, which in turn requires negotiation with unions on the terms of the new job description. This gives the union a high level of power to resist managerial improvements and modernisation efforts, which creates unproductive rigidities in the way public employees are managed. Having broader job descriptions that focus on functions and competencies, rather than specific tasks, would enable a more fluid evolution towards modern digital workplaces.

There is an ongoing project at the Civil Service Commission to simplify and reduce the number of jobs in the job classification system in the public sector in order to introduce more flexibility and create margin for manoeuvre.

On the other hand, there is an over-generalisations of job classification for the pay system, which makes it very difficult to effectively target pay to specific job functions and improve competitiveness in the labour market. For example, employees with social science backgrounds are on the same pay scale, but can work in areas as varied as HR, policy development and regulation. In this instance, Israel’s public sector pay system does not enable certain functions to be remunerated according to their market value because pay is linked less to job content and complexity than to a checklist of input-oriented criteria such as educational background and years of seniority.

This creates particular challenges given inconsistencies with other job classification systems in the private sector. For instance, in Israel, the private sector distinguishes a civil engineer from an electric engineer and compensates these two occupations differently. Conversely, the public sector does not distinguish between engineering degrees for pay purposes. Therefore, they end up paying relatively more for one type of engineer and less for the other. This means that certain types of engineers, in this case, are less likely to want to work for the public sector.

These examples illustrates a double challenge for Israel’s public sector job classification system – highly specific tasks reduce management flexibility, while overly broad pay categories make it difficult to match market value for specific skill sets. Therefore, the goal of any revision to the job classification system should be twofold – to make the specific job descriptions less detailed to enable change and evolution in careers, while, at the same time, making the pay grids more specific to enable different compensation for different occupations, particularly those that are underpaid but in high demand.

Many OECD member countries have experienced these challenges. In the 1990s, many OECD member countries revised their job classification systems (See Boxes 2.3 and 2.4). More specifically, they tried to reduce the number of occupations and to simplify the categorisations in order to gain flexibility. Many also decentralised the classification to specialised public agencies to fit the employer’s needs.

The International Standard Classification of Occupations (ISCO) is an international labour classification designed by the International Labour Organisation (ILO) that helps comparison of national job markets. The European Commission has developed a classification of European Skills, Competences, Qualifications and Occupations (ESCO). Only a few OECD member countries follow the International Standard Classification of Occupations (ISCO-08) to refer to occupations in central government and some have built their own classification closest to their needs. The choice of the appropriate job classification systems depends on the objectives and priorities of the institutions. Since the job classification system implies consideration of the vision for the future, different countries emphasise specific competences or hierarchical structures. Despite differences, these international classification systems can serve as a useful benchmark for Israel.

To conclude, technology evolves, especially in the digital era, and the nature and scope of jobs change over time. Job requirements, contents, and occupations must adapt to this evolving context in order to hire, train, and manage effectively. Drafting flexible job descriptions also implies a profound understanding of what behaviours and competences will be needed in the future. Strategic workforce planning is complementary to a reform of the job classification in order to map existing job classifications and move away from task-based job descriptions toward competency-focused job profiles. Some flexibilities such as technology adaptation are not only related to job classification but also to labour relations which are discussed in greater detail in the next chapter.

Job ‘weighting’ is a component of Job Evaluation (JE) used to assign a numerical value to elements of a job (referred to as ‘factors’) in order to determine remuneration. Some form of weighting – the size of the contribution each factor makes to the maximum overall job evaluation score – is implicit in the design of all job evaluation schemes. Most schemes also have additional explicit weighting. The rationale for this is generally two-fold. It is unusual for all factors to have the same number of levels because some factors are capable of greater differentiation than others. This gives rise to weighting in favour of those factors with more levels, which may need to be adjusted. It is also the case that organisations place different values on different factors, depending upon the nature of the organisation.

The model used in the NHS has a maximum of 1,000 points available. The number of points available for each factor is distributed between the levels on an increasing whole number basis. Within the available maximum number of points for the scheme, the maximum score for each factor has a percentage value, the values being the same for similar factors. The allocation of total points to factors is set out below.

Responsibility: 6 factors: – maximum score 60: – 6 x 60 = 360 – 36% of all available points in the scheme.

Freedom to act: 1 factor: – maximum score 60: – 1 x 60 = 60 – 6% of all available points.

Knowledge: 1 factor:– maximum score 240: – 1 x 240 = 240 –24% of all available points.

Skills: 4 factors:– maximum score for each 60: – 4 x 60 = 240 –24% of all available points.

Effort and environmental: 4 factors: – maximum score for each 25: – 4 x 25 = 100: – 10% of all available points.

Source: NHS

France modified its job classification in recent years to adapt its workforce to the strategic vision and needs of the public sector. In 1988, France adopted statutory measures to improve the status of teachers and nurses, which raised their basic wage without leading to a general increase in public wages. In 1990, France renewed the whole job classification system and pay grid to improve career and pay for the least paid workers, and to take into consideration new skills and responsibilities at the other end of the pay range. It was possible to link pay to a specific job position and not only to pay grid thanks to an additional pay attached to positions and called “bonification indiciaire”.

The new job classification system that has been implemented in 2006 in France is called “le repertoire interministériel des métiers de l’Etat”. It identifies and describes each position or métier. It names and quantifies the necessary jobs within a service; controls for the match between the classification and post; supplies with a reference table of skill to accompany recruitment, mobility, and training; guide and organize the competition for a job position both in external and internal recruitment. In order to increase the efficiency of this job classification, tools were developed: a dictionary of competencies that include formal diploma, knowledge but also social skills and know-how skills; an inter-ministerial job exchange platform; and a mobility kit to help both recruiters and employees to increase mobility.

Designing pay systems around an appropriate job classification system requires a careful assignment of the factors that are used to determine pay. The factors that are used to determine pay refer to aspects that can be based on

inputs, such as level of education, skills and competencies, previous experience;

job characteristics, such as skills requirements, level of responsibility, specific job demands (e.g. physical danger, working time, etc);

These factors can apply to various structural components of pay, including base wages and any additional payments such as allowances or performance bonuses. This section looks aligning pay more closely to job characteristics and performance, and at rationalising the complex pay structure.

Using job characteristics to set pay levels

A strategic pay system would use pay to attract, develop, retain and motivate the competences the government needs in the future. In Israel, the pay system mainly rewards education and seniority, rather than specific competencies, responsibilities or management skills. Basing pay on broad inputs related to education and seniority limits the link to productivity and effective service delivery. On the other hand, if the job classification is too narrow, pay must be raised at the smallest change in job requirement, which is not only difficult to manage but weakens the ability to adapt to change (see discussion in the previous section).

An additional challenges in Israel is that pay is determined not only by the job classification but also by relative pay in other job classifications. This means that an increase in pay for one specific job position results in disproportionate effects both in the short term (wage) and in long term (pension) through automatic global increases through the whole pay grid. The challenge in Israel is to disaggregate the web of social agreements and the pay grid so that a case-specific intervention on a job position does not result in automatic and global effects.

One option would be to move from pay tables based solely on education and seniority to pay tables based also on specific professions, grades, responsibilities and competences, such as outlined in Box 2.5. A pay system based on job characteristics would also enable employers to adjust compensation for specific groups (if under market value) without impacting the compensation of others (who may already receive above market value).

In the UK civil service, government departments have delegated authority to set pay and terms and conditions of employment for junior grades, subject to compliance with some controls. These controls include the Annual Pay Remit Guidance which sets the parameters for departments making pay awards. This includes the ability to make a business case to make a pay award that is higher than the Pay Remit Guidance allows. A business case can address one of the following criteria: (i) transformational workforce reform; (ii) recruitment and retention issues; and (iii) when transferring funds for bonuses – ‘non-consolidated pay’ – to the regular pay envelope (Cabinet Office, 2020[5]). This could present an interesting model for Israel to explore. However, this would be a large reform and that would require careful design (and change management) based on discussion with all stakeholders including politicians, leaders, managers, employees and their unions.

There is no one unique pay system in the UK. The Cabinet Office has responsibility for the overall management of the Civil Service. It is responsible for publication of the Civil Service Pay Remit guidance (covering the pay of junior Civil Service grades) and ensuring that it is affordable and flexible enough for all relevant departments to apply within their budgets. Pay for senior grades is set centrally through annual Senior Civil Service (SCS) pay guidance based on recommendations from an independent pay review body, the Senior Salaries Review Body. HM Treasury has overall responsibility for the government’s public sector pay and pensions policy, and maintaining control over public spending including with regards to departmental spending. Departments have responsibility for implementing Civil Service pay policy for their workforce in a way that is consistent with the Civil Service pay guidance but also reflects the needs of their business and their labour market position. All pay remits must be approved by a Secretary of State or responsible minister, and each department, through its accounting officer, is responsible for the propriety of the pay award to staff.

Each agency or department designs its own pay scale for junior grades in order to match its particular needs. The basic salary is linked to an “individual's value to the organization” measured by job weight/grade. There are usually 7 grades in each department as well as three senior management grades (the pay ranges in the latter are set centrally by the Cabinet Office). Hence it’s not automatically given by a pay scale related to education or experience, but depends on various variables that reflect the “size and challenge of the job; professional and leadership competence; an individual’s market value”.

In 2008 a report to the cabinet Secretary advocated reforms to improve senior civil service. It pushed forward a new reward model that differentiates pay in five items, base pay according to a job classification, pension, an additional pay relative to job weight, content and responsibility, a premium for scare skills and expertise and bonuses to reward performance. The basic wage rewards education and competencies and has 4 to 5 grades to reward experience.

A complementary approach could be to expand the use of shorter-term contracts to specific positions. In 2015, the Israeli government decided to employ most senior levels of the civil service (DGs and some deputies) with time-bound contracts, limiting their duration to no longer than 6 to 8 years. The purpose of this reform was to create a competitive environment for senior employees since these contracts enable higher salaries to be paid for in-demand skills, as well as inducing a higher turnover rate in senior management, thereby creating more dynamic organisations. This is in line with good practice in many OECD countries. The reform included a limited number of positions, which account for less than 1.5% of all positions in the Israeli government. The Israeli government could consider expanding this employment model to some additional high-level management jobs or to specific technological positions, for example.

Simplifying the pay structure, rationalising allowances

Pay structure refers to the balance of the base wage and any additional payments, regularly paid (e.g. allowances for specific aspects of the job) and not regularly paid such as bonuses for performance. While some additional payments will be necessary to compensate for special features of some jobs and enable some level of flexibility in the across the pay grids, it is generally preferable to structure pay so that the base wage is as large a proportion as possible. This helps to ensure that pay is transparent, fair and easy to manage. Nevertheless, additional payments can make up sizeable portions of the public sector wage bill. For example, in the central public administrations of Italy, Spain, and France, additional payments may represent up to 30% of the gross wage, and sometimes 50% especially for senior positions or highly ranked managerial positions.

The share of additional payments in Israel is high. On average basic wage is only around 46% of total compensation for general government civil servants, with a lowest share of 28% in the health system where doctors can have additional pay in the private sector, and a higher share of 80% in the education system.

Simplifying the existing pay structure would be a useful exercise to increase transparency for both employees and employers. On top of the base salary, many additional payments depend on factors such as experience, location, and family situation. These allowances are usually the result of collective bargaining processes, and therefore tend to be incremental changes that may be applied unevenly based on the strength of the union, rather than the result of strategic decisions taken by the government to build an effective public workforce. Over time, these various components are added to, increasing the complexity of pay across different job categories.

This complexity blurs information on pay for a specific job positions, and lack of transparency limits recruitment and mobility. In Israel, it is difficult for recruiters to advertise the specific pay of a job because it is context-specific – it depends on many factors including the particular situation of an applicant. This makes it very difficult to advertise pay information in recruitment campaigns and attract good candidates. This also affects internal mobility, as civil servants may not be able to easily identify potential remuneration for another position in a different Ministry or agency, for example. Removing various allowances from collective agreements could make funds available to raise base salaries in positions which are currently under-paid.

Allowances are an important component of public sector pay in Israel, valued in many cases by employer and staff alike for their link to motivation and engagement. However, many allowances are the result of labour negotiations from a long time ago, and may now be disconnected from the reasons why they were implemented in the first place. For instance, the car allowance would be a potentially useful candidate for rationalisation: initially designed to compensate employees for the cost of using a car and to improve working conditions, it resulted in an incentive to buy and own a car instead of using public transportation. This now contributes to pollution, traffic congestion, and a requirement to provide parking. Other additional payments that could be theoretically efficient have been expanded to more workers than needed, creating a paradox of aggregation. For instance, readiness pay is paid to workers available after working hours and might be less relevant nowadays, except for only specific professions.

Training allowances are another candidate for modernisation. These allowance are attributed to employees for acquiring new skills, however the list of specific courses dates to collective agreements from the 1970s and are outdated, therefore they don’t always match with the needs of employers. Though the initial purpose of those training rewards was to increase incentives for employees to invest in their competencies, this situation today results in perverse effects: employees are less willing to accept other learning opportunities that do not open the right for new allowances; components of wages are fixed without the employer’s evaluation; and mobility between positions is reduced because pay is not linked to job position. Training in some cases appears to be seen less as an essential component of life-long learning, and more as an inconvenience to be offset with concessions from the part of the employer. Therefore, Israel should carefully review these payments which no longer appear to meet the objectives for which they were designed.

Lifelong learning is essential to evolving in one’s career, to adapt to technological changes and to respond to citizens’ needs. Well-designed and adapted learning programmes are essential and need to be preserved, evaluated regularly, and upgraded. The issue is to implement the right set of incentives to both employer and employees to reward learning. In theory, there is no need to reward training by an allowance. If training is effective, it increases performance hence it should enhance career development and increase wages. Rarely do OECD countries rely on direct financial payments to motivate staff to undertake training. Rather, to increase individual learning incentives, training is often linked to performance management processes, to ensure that civil servants receive the training they need to perform and progress in their careers, and that training provision is effectively coordinated. Mentoring, peer learning and mobility assignments can also help to promote learning. Hence, Israel would benefit from rethinking its training incentives and reducing the direct link between wage and hours of training.

To summarise, there is significant scope to streamline the structure of the pay systems and significantly reduce the number of allowances. The simplification of the pay structure (base wage, additional payments, working time, benefits) is the first step for transparency, and hence an efficient and inclusive pay system. Additional payments that are historically set do no longer fit their purpose and are not an efficient way to increase pay. The pay system needs to rely not only on education and seniority but also managerial responsibilities, relative pay to the private sector and working conditions. The adaptability of the pay system is a necessary condition to adapt the workforce composition to public service delivery needs. Some OECD countries have established independent pay review bodies to provide recommendations on pay in line with strategic priorities (Box 2.6).

Ireland: In 2016, the Irish Government approved the establishment of an independent Public Service Pay Commission (PSPC) to advise Government in relation to public service pay. The Commission comprises a Chairperson and seven members, all of whom were appointed by the Minister for Public Expenditure and Reform. The Commission produces a series of reports providing recommendation to government on various aspects of how pay affects attractiveness, recruitment and retention.

United Kingdom : The Office of Manpower Economics provides an independent secretariat to the following eight Pay Review Bodies which make recommendations impacting 2.5 million workers (around 45% of public sector staff) and a pay bill of £100 billion: Armed Forces’ Pay Review Body (AFPRB); Review Body on Doctors’ and Dentists’ Remuneration (DDRB); NHS Pay Review Body (NHSPRB); Prison Service Pay Review Body (PSPRB); School Teachers’ Review Body (STRB); Senior Salaries Review Body (SSRB); Police Remuneration Review Body (PRRB); National Crime Agency Remuneration Review Body (NCARRB).

United States: Under the Federal Employees Pay Comparability Act of 1990 (FEPCA), the Federal Salary Council makes recommendations on Federal pay. In 2019, these recommendations covered estimated locality rates; the establishment or modification of pay localities; the coverage of salary surveys conducted by the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) for use in the locality pay program; the level of comparability payments; and the process of comparing General Schedule (GS) pay to non-Federal pay.

Performance-related pay

Performance-related pay (PRP) systems link pay bonuses and/or increases to defined performance indicators. The effectiveness of PRP systems depend on system design and organizational context. Five key aspects need to be taken into consideration when designing PRP systems:

Defining performance: clear and measurable targets evaluated through excellent performance appraisal systems

Time horizon: short-term or long-term incentives, based on periodic performance appraisals

Size of the incentive: establishing a motivational incentive while preventing unintended consequences

Probability to receive an incentive: how common should it be to reward high-performing civil servants

Linking pay to performance is intended to motivate employees, and to compensate them for exceptional effort. However, public sector employees are often highly skilled professionals who work in an environment where performance is difficult to measure. Hence, the evaluation procedures need to be consistent with employee’s aspirations, intrinsic motivation and willingness to perform. When the wide objectives of the institution match employees’ personal objectives and when the quality of management is well perceived, then, PRP is more likely to be effective. In Israel, the current pay system does not appear to enable managers to effectively reward talent and performance.

If nearly all OECD countries have implemented some form of PRP, few have succeeded in designing an effective system of bonuses. Studies have reported weaknesses in PRP in the public sector and little evidence for increased motivation or increased quality of public services. The small share of bonuses in total compensation, the complexity of performance assessment, and the multitasking problem are commonly reported difficulties. Nevertheless, the PRP can be useful in raising and signalling performance norms across public sector organisations.

Overall, in OECD member countries, there is high diversity with no clear best practice PRP. However, a number of principles that make up a good PRP system include:

Perceived legitimacy – a PRP system only works if employees and employers agree that it rewards the right people for the right things. This suggests the need for simplicity and transparency, for differentiation of rewards.

Alignment of criteria between individual performance and organisational results – PRP should reward people whose working behaviour is conducive to achieving organisational objectives. However getting this link right is very challenging, especially when organisational objectives rely on collaboration, and when the organisation is working in uncertain environments where simple production of measurable outputs is not necessarily aligned to the achievement of desired outcomes.

Tools to deal with low performance – discussions of PRP usually focus on the reward for the top group, but equally important is how to deal with those that receive low performance ratings. If managers don’t have tools and incentives to manage their low performers, then they will often hesitate to use the performance system at all.

The perception of the PRP system is a key factor in its success. When perceived as controlling, it crowds out intrinsic motivation. However, when perceived as supportive it could complement and reinforce intrinsic motivation. Wenzel et al (2017[6]) show that a “fair, participatory, and transparent design” may both reduce the complexity cost of a PRP system and foster the intrinsic motivation of employees. Fairness is an important factor in the implicit contract behind the PRP system. A PRP system is perceived as fair when performance pay is not based on random performance ratings and there is a direct link between the amount of performance pay and the perceived quality of performance. A pay system may be perceived as unfair if performance pay is based on favouritism, on flawed performance evaluation systems, or on a system that results in low levels of differentiation – i.e. a low level of pay bonus.

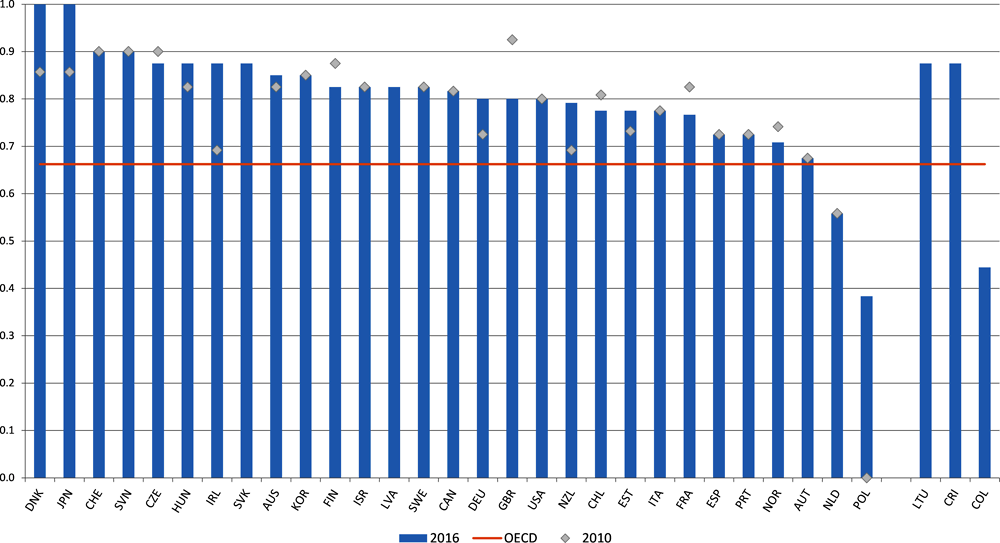

PRP systems earned an important place in most public sector reforms since the 80’s. Two-thirds of OECD member countries use PRP for government employees (OECD, 2005[7]). In France, Canada, and New Zealand, PRP is primarily used for senior managers, whereas in most other OECD member countries PRP applies to most public employees. Israel has implemented PRP that targets mainly non-managerial employees. As indicated in Figure 2.1, on a composite indicator that measures the extent of the use of PRP in central government, Israel makes more extensive use of PRP than other career-based systems like France or Spain.

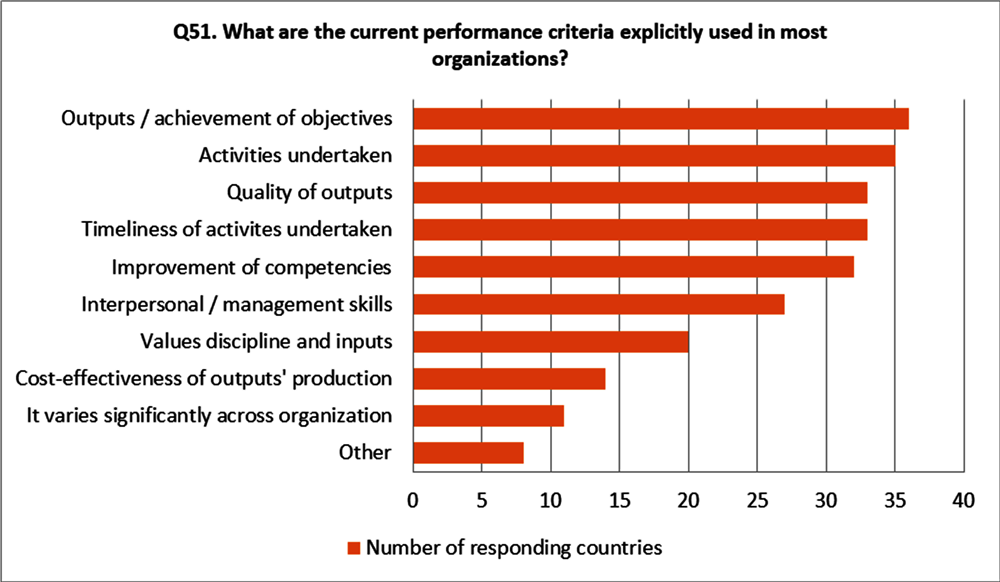

Performance assessments are used in all OECD member countries, except Iceland and Norway, for nearly all public employees. However, there is an important heterogeneity among OECD member countries in the way performance is measured, assessed and translate into pay. Like in Israel, meetings with superiors or written feedback from superiors are usually held once a year and 360° evaluations are rarely used. The performance criteria used in Israel looks like the criteria used in all OECD member countries (Figure 2.2). However, in other OECD member countries, the choice and use of the criteria are usually decentralized to local institutions and departments. This decentralization allows the criteria to meet the needs and specificity of the sector and organisational environment.

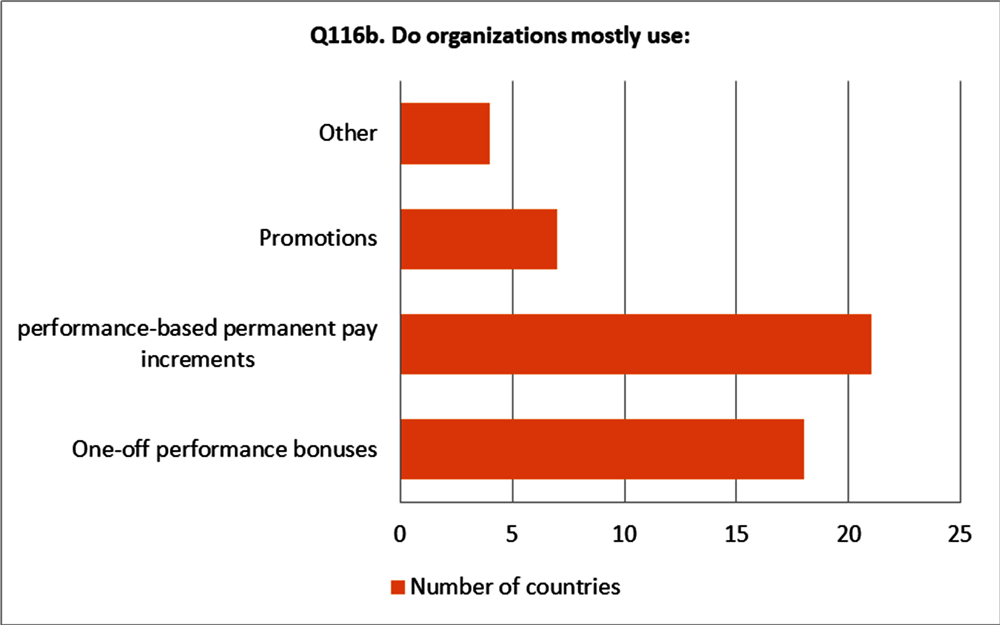

The maximum amount of PRP related to base wage is not over 20% in most countries. PRP takes various forms (Figure 2.3), and most often either a one-off performance bonus, which corresponds to the idea of giving incentives, or a permanent pay increase, which is due to either promotions or the use of PRP as an increase in the base wage.

In Israel, various forms of pay for performance were introduced after a collective bargaining agreement signed in the late 1960s (the 1969 collective agreement on incentive pay) and includes premium payments, premium in training and premium on leave. In 2017, about half of the 72,000 employees who work in government offices and hospitals were eligible for bonuses linked to performance, and of those, about 95% received 95-11% of the maximum amount of their possible bonus (Israel Ministry of Finance).

The complexity of the public service ‘good’: Public services generate a multitude of outcomes, some of which are more easily measured than others. In addition, the ultimate outcomes of many public sector activities may only be visible in the long-term, raising questions about the feasibility of accurate and meaningful performance measures within a PRP scheme.

Multiple principals: The public sector involves a wide variety of potential ‘owners’ and stakeholders (service users, managers, unions, professional bodies, the Government, taxpayers). Any PRP scheme in the public sector must be capable of reconciling the variety of outcomes from these multiple stakeholders and interests.

Multi-task problems and collaborative activity: The delivery of public services tends to be a complex and inherently collaborative activity. Attributing individual responsibility for performance and outcomes may therefore be challenging, and individual incentives could mitigate against team work.

Misallocation of effort: PRP schemes may incentivise outcomes which are more easily and directly measurable (OECD, 2009), encouraging employees to focus on these outcomes at the expense of others, e.g. ‘teaching to the test’ in education.

Gaming: When performance indicators become ‘high stakes’ employees may attempt to game the system (Neal, 2011), where workers seek to maximize their gains while minimizing effort or without increasing performance. This can lead to significant problems in the public sector, where outcomes can have a wide social impact.

Source: The Work Foundation (2014), A review of the evidence on the impact, effectiveness and value for money of performance-related pay in the public sector, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/381600/PRP_final_report_TWF_Nov_2014.pdf

Israel’s original PRP was not intended to reward individual performance. At the beginning, the measurement of performance was made at the group level and the variable pay was addressed to the unit. This kind of collective incentive can be effective when the performance is difficult to measure at the individual level or when collaboration is crucial in the job position. Collective rewards tend to increase group cohesion and cooperation between employees, but do not increase individual performance and do not attract competencies. Indeed, collective PRP can have a negative retention effect on the most productive employees that would seek more productive groups or a negative effect on motivation for those who range above the average performance.

Furthermore, these group incentives require two conditions to work well. First, there must be legitimate ways of measuring performance, and second, the work these groups do must be comparable to others. This means that this tends to work well in stable operational environments - for example, offices that process drivers’ licenses or that deliver specific sets of citizen services in similar ways to others.

In Israel, variable pay was first addressed to work teams with measurable productivity. A committee including management and union representation sets the methodology by consensus, and all stakeholders must agree on any change to the calculations. However, over the years, this has been extended to include administrative and headquarters work as a result of labour negotiations. Determining productivity metrics for administrative positions is particularly difficult (see Box 2.7).

Once set, it is procedurally difficult to change the way performance is measured for each of the groups in Israel’s system. This is due to the multiple stakeholders (e.g. management, employees and their unions) who need to agree – each has a veto to any changes proposed. This seems to result in out-of-date performance metrics, which no longer make sense in a modern work environment. Over time, this pay becomes seen as entitlements to be spread around evenly rather than to differentiate and reward genuine performance. Once this happens, unions have little incentive to agree to changes that improve the performance metrics used.

This is not a problem unique to Israel. In many other OECD member countries, pay for performance has become an additional payment rarely linked to effective performance indicators. This misuse of variable pay is counterproductive since it fails to reward performance but also creates frustrations and misaligned expectations. This may be due to various factors, including a lack of managerial capability, institutional settings, and the centralised nature of the PRP process.

Recognising these challenges, a different kind of PRP focused on individual incentives has been introduced into headquarters units. Since measuring performance in services is challenging, a “differential system” comparing relative employee performance has been introduced more recently. This second system appears to be easier to implement since managers don’t need to assess very precisely the performance indicators but need only to be able to compare individual employees. This individualised approach can be efficient but may be detrimental in collaborative working groups. If there is a given amount available for a particular group, colleagues could hypothetically take a “zero-sum” approach suggesting that more bonus for themselves requires less for the others. Hence, this gives the wrong incentives to work against colleagues’ performance, and risks increasing the level of competition and conflicts in the workplace.

The effectiveness of PRP depends on managers with the right skills and tools to properly assess performance and then manage staff with low performance. When managers have little discretion to address low performance, and when managers fear the social impact or peer pressure of not rewarding someone, PRP can be counterproductive and detrimental to the entire performance evaluation system. In the case of the group evaluation method, managers have no discretion as the performance metrics are set in committee with unions and employees. As mentioned above, this may work well in operational setting with clear and comparative performance metrics. However, it is likely not well suited to many of the work settings in which it is currently implemented – in these cases it may be best to transition to an individualised system with effective managerial support.

PRP may also be badly designed because of institutional settings. Since in career-based systems dismissals are difficult, PRP ends in relative pay increase, hence potential social conflicts, or on the contrary smooth increase for all hence no incentive effects. The performance indicators once decided for remain often rigid and don’t adapt to a change in objectives or working conditions. Moreover, managers don’t always have the discretion to set bonuses that can be decided for at the centralized level or even by the employee’s delegates at local pay committees.

Given the variety in PRP, and given the wide set of undesirable effects in using PRP, it is not possible to recommend an optimal method. Each institution, each department would profit from a PRP system designed for local needs that reflect the employees’ values and culture. Decentralization and differentiation in measurement methods and translation into pay are likely to make the whole system more legitimate and flexible, assuming effective controls on abuse are in place. Israel may wish to run a review of all the current arrangements in place with a focus on two objectives. The first is to identify teams subject to the group pay for performance processes which should transfer towards an individual system. This would entail groups which to do not do easily measurable and comparable work. The second focus of the review could be to look at those groups for whom collective rewards make sense, but require updates to their reward mechanisms.

Moreover, decentralization of PRP has another advantage of making the wage bill more predictable. When pay increases are decided at the centralized level, PRP may end in general increase, since the Ministry of Finance can be pressured to increase pay for all since it is the last resort decision maker. Alternatively, the ministry of finance could give a small percentage of the overall wage bill to each agency and allow the management to use it for performance pay as they see fit, with appropriate guidelines in place to avoid abuse. These guidelines usually include mechanisms to ensure transparency, oversight by senior leadership, and peer review. For example, a manager who wants to provide a bonus would need to gain approval from the Director General of their Ministry, and justify their rationale to their peers in their management team.

Targeted pay increase and performance rewards are easier to implement at a decentralized level. For instance, in the UK, individual departments have a budget and decide how to spend it and can target pay rewards to specific positions and employees. Decentralized pay leaves individual managers more flexibility to reward good performers and attract needed skill sets while not impacting the overall wage bill.

To conclude, a pay system should recognise and reward excellence and exceptional performance. Nonetheless, it can be complex to reward performance without jeopardizing intrinsic motivation, trust, and public values. PRP naturally appeals to our sense of justice and can be theoretically efficient, but badly designed systems are abundant, and can be detrimental to employee motivation, team cohesion and organisational effectiveness. An effective PRP system must be perceived as fair by all involved stakeholders – in particular the employees and the managers, and therefore relies on employee buy-in and managerial discretion. Employees and/or their representatives should be involved in the design of the system, but managers need discretion and support to make the system work effectively. However, PRP is not the only way to address the challenge of rewarding performance, and a more flexible pay scale or larger mobility opportunities can be more effective when understood and well-perceived by the employees. Career mobility is also a very effective incentive, which is discussed in the next section.

In 2013, a new system of performance pay for school teachers was introduced in state primary and secondary schools. The former pay system enabled six annual pay increments by performance-based progression, on the ‘main scale’. The objectives of the new system were to introduce the performance element in progression between the main and the upper pay scales, and to better take into account the performance element on the three points on the upper pay scale. The objectives are agreed upon at the start of the school year. Then after mid-year feedback, at the end of the school year, a final assessment contrasts the results on the national teacher’s standard and the agreed objectives. The school senior management reviews the recommendation on pay given in the final assessment and decides on the merit-based pay. National school inspectors from the Office for Standards in Education, are in charge of checking whether performance awards are efficiently used

Source: Marsden, D. (2015) Teachers and performance pay in 2014: first results of a survey, Centre for Economic Performance, CEP Discussion Paper No. 1,332

When job classification and pay systems lead to identical or comparable pay ranges for comparable positions, they can encourage employees to move between organisations and units, hence increase mobility. Mobility in the public sector can increase motivation, experience and competency development. Career mobility can be an effective way to reward talent and performance. In Israel, given the small share and use of individual performance related pay (PRP), promotions are an important way to incentivize effort. When promotion and hiring of government employees is a function of their competencies and performance – i.e. merit-based HRM - governance of the public system is enhanced.

In most public sector pay systems, pay increases with seniority within the same job position. Pay increases with seniority for two main reasons: first, experience increases productivity hence an efficient pay system must reward time spent on a job; second, pay increases with seniority in an “implicit contract”. The idea of this implicit contract between the employer and the employees is to pay less when the employee is young and higher when older, in order to keep employees in the job position. By paying them less today but more tomorrow, the employer gives incentives to stay and wait to benefit from the seniority effect. Keeping them in the administration or the firm when they are young is useful when there is a specific human capital to invest in. This specific human capital covers training, competencies, knowledge worthy in the public sector and that may be useless in the private sector or on another job position. If the employee plans to quit the public sector, then it is not worth investing in specific human capital. Consequently, salaries rise more quickly than productivity with seniority, in order to increase the incentives to specific training and to keep young talent.

Today the age-wage profile has become flatter in the private sector but also in the public sector in most OECD member countries, for instance in Japan, Korea but also in the United States and France. One reason is that the rhythm of change in technology makes it more appealing to hire young and competent employees without committing to long-term employment. Another reason might be the weakening of specific human capital for public sector jobs. Training on digital competencies, for instance, will be useful on the job market and not only in the specific institution.

Mobility between the private and the public sector and mobility between firms weakens the implicit contract. Hence, managers can pay according to productivity all along the career and the rate of increase of pay with seniority is expected to be lower.

In Israel, the public sector still gives a high weight to seniority in salary. If the relative pay of older employees to younger employees is higher in the public sector than in the private sector, a shortage of young public employees is to be expected. Even if on average, one finds no pay gap between the public and the private sector, there could be an important misalignment by age. If the private sector follows the implicit contract effect less than the public sector, then younger employees will be paid according to their productivity and not less, hence young employees will be less attracted to the public sector.

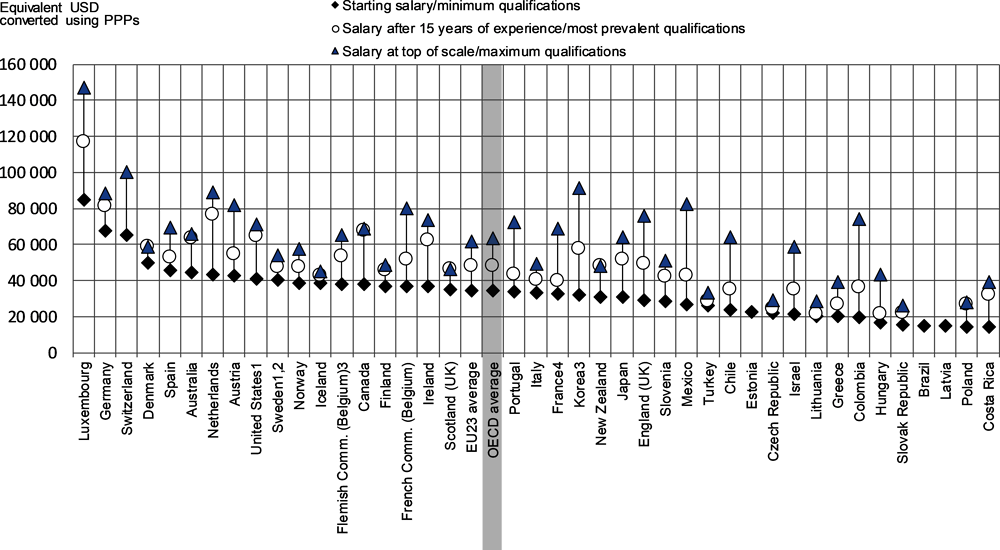

For instance in the education sector, the wage gap between young and older teachers in Israel is rather wide compared to other OECD member countries (OECD, 2019[8]). Among the secondary teachers (Figure 2.4), on average an older teacher that reaches the salary at top of scale earns around 2.7 times more than a younger teacher at the starting salary in Israel, whereas the ratio is on average 1.8 across OECD member countries, 2,1 in France, 1.7 in the United stated, 1,3 in Sweden and Germany. This will likely have a negative impact on the number of, and quality of young people who wish to become teachers in the public system. To limit this reduced attractiveness of the public sector for young teachers, in March 2018, a labour agreement was signed by the government, local authorities and the high-school teachers’ union that implemented an increase in wages for teachers starting their career by approximately 20%. Those teachers make up about 6% of the teachers in Israel as of 2018.

The evolution of salary along the career is linked to the pension system. In Israel, in 2002 a pension reform took place which began a shift from a defined benefit plan to a defined contribution plan. In a defined benefits plan the employer guarantees a retirement benefit amount based on the employee’s salary and years of service. A defined contribution plan is funded by the employee who defers a portion of their gross salary, with the employer matching contributions to a certain amount. Israel chose to implement the transition between the two systems by not allowing new employees to be on the defined benefits plan. The number of employees on a defined benefit plan is decreasing over time since the new workers are on a defined contribution plan.

This transition distorts incentives between workers for a pay increase. The new workers on defined contributions pensions save their whole career hence care greatly about their wages when young since early savings offer a greater opportunity to compound over their lifetimes; whereas the old workers on defined benefits plans care more about their wages at the end of their career, since this calculates their retirement benefits. It seems challenging to have workers doing the same job but having different pensions systems and gaps between workers may weaken motivation. Consequently, this pension reform exerts additional pressure on rebalancing pay to provide higher pay early in careers and less later, meaning giving less weight for seniority in pay determination.

To conclude, promotions are an effective tool to reward performance and talent when they are based on assessment of competence and performance, rather than being automatic based on seniority. The importance of seniority in pay is inconsistent with the reform of pensions Israel has implemented and the changes expected in the future of work, and a decreased use of seniority compared to other variables could help in attracting young talents.

In order to improve Israel’s public sector pay system and ensure it supports a public service which is forward-looking, flexible and fulfilling to a diverse range of public services, the Israel government could aim to:

1. Develop a common strategic vision for the future of the public sector in Israel. This should include a specific focus on which skills and competencies need to be developed and how. This could be done centrally, but also in individual sectors, agencies and ministries. It should be an inclusive activity bringing together the Ministry of Finance, Civil Service Commission, line managers and employees. It can then be used to guide pay reforms and collective bargaining processes.

2. Reduce the number and specificity of job classifications. Greater standardisation of positions across the public sector would enable mobility between and across Ministries. Mapping and grouping job types enables targeted interventions to help staff adapt and upskill in a context where digitalisation and other trends are re-shaping work, workforces and workplaces. Revised job classifications that focus on competences is key to embedding greater flexibility, i.e. the understanding that all jobs will and must change their scope.

3. Align pay more closely with the competencies and complexity demanded in positions. Building on the recommendation above, linking pay more clearly with the complexity and ‘weight’ of a job rather than static indicators such as educational background would encourage high performance and attract needed skill sets. This may call for a Job Evaluation exercise targeting specific professions. This review could be piloted for areas of the public service demonstrating clear evidence of a persistent inability to recruit and retain specialised and high-value skill sets.

4. Rationalise the structure of pay to increase base pay vis-à-vis additional pay. Many allowances are no longer linked to the reason they were introduced in the first place. This complexity impedes recruitment and mobility. Other allowances may have unintended side effects, such as creating an expectation of compensation for undertaking training. Reviewing and rationalising certain allowances would help create greater clarity on pay. This could free up funds to be used more strategically, e.g. for targeted pay increases.

5. Unwind links between and across pay groups. Currently, the web of collective agreements means that it is difficult to adjust pay in one area without creating knock-on expectations or automatic adjustments in other unrelated areas. While respecting unions’ prerogatives to defend their members, there should be greater ‘ring-fencing’ of the scope of negotiations between the government and unions. This means that negotiations would focus on a clearly defined population, allowing more nuanced adjustments to collective agreements and ultimately, mutual gains.

6. Establish a list of hard-to-recruit profiles/positions and pilot creative ways to align pay with relevant market levels. Pay is not the only factor determining why people apply to and remain in the public sector, but it is an important factor. Increasing pay to an acceptable level for specific and high-value positions could be funded from efficiency gains elsewhere to raise base salary, or through performance-related payments based on rigorous criteria.

7. Decentralise and review pay-for-performance systems. Israel’s dual performance pay systems (group or individual) should be reviewed and rebalanced – focused on better aligning the system with the nature of the work. This will likely result in a number of areas currently under the group regime transitioning to the individual regime, for which managers need a degree of autonomy to allow them to set performance norms and reward high performers, while remaining within an agreed-upon budget ceiling. This discretion should be framed by clear, rigorous and periodically reviewed guidance and support. For groups that remain in the group system, performance metrics should be updated regularly, to ensure continued relevance. The committee system should also be reviewed to ensure they provide managers and employees with the right tools to set effective performance indicators.

8. Reduce the importance of seniority-based pay. To be effective as incentives, pay and promotions should be linked with actual performance rather than only static indicators, such as seniority (length in post). Entry-level or starting salaries could be made more attractive in line with an increased emphasis on performance management and merit-based promotions.

9. Expand the time-bound contract employment model. Expanding this contractual modality to additional management jobs or to technological positions could be a key driver of greater flexibility and attractiveness. The purpose of this reform was to create a competitive environment for senior employees since these contracts enable higher salaries to be paid for in-demand skills, as well as inducing a higher turnover rate in senior management, therefore creating a more dynamic organisations.

References

[5] Cabinet Office (2020), Civil Service pay remit guidance 2020/21, https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/civil-service-pay-remit-guidance-202021/civil-service-pay-remit-guidance-202021#pay-flexibility.

[3] Gallup (2016), How Millenials Want to Work and Live, https://www.gallup.com/workplace/238073/millennials-work-live.aspx.

[1] Mazar, Y. (2018), “Differences in Skill Levels of Educated Workers Between the Public and private Sectors, the Return to Skills and the Connection between them: Evidence from the PIAAC Surveys”, Bank of Israel Working Papers, Vol. 2018/1, pp. 1-28, https://www.boi.org.il/en/Research/DiscussionPapers1/dp201801e.pdf.

[8] OECD (2019), Education at a Glance 2019: OECD Indicators, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/f8d7880d-en.

[2] OECD (2018), Policy brief on the Future of Work: Putting faces to the jobs at risk of automation, https://www.oecd.org/employment/Automation-policy-brief-2018.pdf.

[7] OECD (2005), Performance-related Pay Policies for Government Employees, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264007550-en.

[4] Postel-Vinay, F. and H. Turon (2007), The Public Pay Gap in Britain: Small Differences That (Don’t?) Matter, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0297.2007.02091.x.

[6] Wenzel, A., T. Krause and D. Vogel (2017), Making Performance Pay Work: The Impact of Transparency, Participation, and Fairness on Controlling Perception and Intrinsic Motivation, https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0734371X17715502.