Dizang asked Fayan, “Where are you going?” Fayan answered, “Around on pilgrimage.” Dizang then asked, “What is the purpose of pilgrimage?” Fayan replied, “I don’t know.” Dizang said, “Not knowing is most intimate.”

Book of Serenity, Case 20

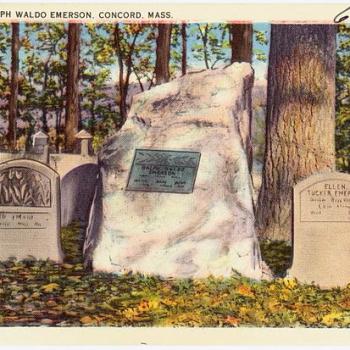

(What follows is a passage from Henry David Thoreau’s lecture, Walking. He drew partially from his journals and in total seemed to have worked on it for several years. The complete essay ws first delivered as a talk at the Concord Lyceum on the 23rd of April, in 1851. He delivered it as a public talk a total of ten times, which is said to be the most he delivered of any of his essays. It was first published in the Atlantic Monthly two months after his death in 1862. The epigram and the title I add in appreciation for the Zen sense of these four paragraphs…)

On Not Knowing

Henry David Thoreau

We have heard of a Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge. It is said that knowledge is power, and the like. Methinks there is equal need of a Society for the Diffusion of Useful Ignorance, what we will call Beautiful Knowledge, a knowledge useful in a higher sense: For what is most of our boasted so-called knowledge but a conceit that we know something, which robs us of the advantage of our actual ignorance? What we call knowledge is often our positive ignorance, ignorance our negative knowledge. By long years of patient industry and reading of the newspapers—for what are the libraries of science but files of newspapers?—a man accumulates a myriad facts, lays them up in his memory, and then when in some spring of his life he saunters abroad into the great fields of thought, he, as it were, goes to grass like a horse and leaves all his harness behind in the stable. I would say to the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge, sometimes, “Go to grass. You have eaten hay long enough. The spring has come with its green crop.” The very cows are driven to their country pastures before the end of May, though I have heard of one unnatural farmer who kept his cow in the barn and fed her on hay all the year round. So, frequently, the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge treats its cattle.

A man’s ignorance sometimes is not only useful but beautiful—while his knowledge, so called, is oftentimes worse than useless, beside being ugly. Which is the best man to deal with: He who knows nothing about a subject, and, what is extremely rare, knows that he knows nothing, or he who really knows something about it but thinks that he knows all?

My desire for knowledge is intermittent, but my desire to bathe my head in atmospheres unknown to my feet is perennial and constant. The highest that we can attain to is not knowledge but sympathy with intelligence. I do not know that this higher knowledge amounts to anything more definite than a novel and grand surprise on a sudden revelation of the insufficiency of all that we called knowledge before—a discovery that there are more things in heaven and earth than are dreamed of in our philosophy. It is the lighting up of the mist by the sun. Man cannot know in any higher sense than this, any more than he can look serenely and with impunity in the face of the sun. “You will not perceive that, as perceiving a particular thing,” say the Chaldean Oracles.

There is something servile in the habit of seeking after a law which we may obey. We may study the laws of matter at and for our convenience, but a successful life knows no law. It is an unfortunate discovery certainly, that of a law which binds us where we did not know before that we were bound. Live free, child of the mist—and with respect to knowledge we are all children of the mist. The man who takes the liberty to live is superior to all the laws by virtue of his relation to the lawmaker. “That is active duty,” says the Vishnu Purana, “which is not for our bondage; that is knowledge which is for our liberation. All other duty is good only unto weariness; all other knowledge is only the cleverness of an artist.”