Analysis: The rules and rituals around Amhrán na bhFiann at matches have lead to controversy, resistance and protests

This article is now available above as a Brainstorm podcast. You can subscribe to the Brainstorm podcast through Apple Podcasts, Stitcher, Spotify or wherever you get your podcasts.

If you have ever been to a county final or an intercounty GAA match you know the routine. People pay attention when the anthem starts and some lads take off their hats. After using the first few lines to suss out how loud everyone else is singing, they mumble through the rest of the song. This well-rehearsed routine is part of the GAA's complex relationship with Amhrán na bhFiann, which is littered with rules that are largely ignored, and acts of resistance.

Written by revolutionary Peadar Kearney around 1907, it's worth remembering that Amhrán na bhFiann is a battle song. After becoming popular as a marching and rallying song among members of Cumann na mBan, the Irish Volunteers and the Irish Citizen Army during the Irish Revolution, it was officially adopted as the Irish national anthem in 1926.

There is no doubt as to its connotations with fighting. The song’s last two soaring lines are 'Le gunnaí scréach trí lámhach na bpiléar, Seo dhíbh canáigh Amhrán na bhFiann’. In English, this translates as ‘Mid cannon’s roar and rifle’s peal, We’ll sing a soldier’s song’. With its rousing melody and celebration of heroism, the anthem is a natural fit at GAA matches. Of course, Gaelic games are by no means an outlier, as pausing for patriotism before a game is a sustained tradition across many sports.

We need your consent to load this rte-player contentWe use rte-player to manage extra content that can set cookies on your device and collect data about your activity. Please review their details and accept them to load the content.Manage Preferences

From RTÉ Archives, a recording of Amhrán na bhFiann, arranged by John Francis Larchet (1884-1967), being performed by the Station Orchestra in 1937

It is difficult to pinpoint exactly when the national anthem became a regular part of GAA matches. Aided by the introduction of large sound systems in GAA grounds, the national anthem has become something people expect when it comes to the big match day experience. But the anthem's adoption at GAA matches has given way to a new pastime, almost as beloved as Gaelic games themselves: complaining about people’s behaviour during the national anthem.

In 2018, Lord Mayor of Cork Tony Fitzgerald wrote to the Cork County Board asking all GAA players to give the national anthem their full attention when it is played before games, as he was concerned at people's reluctance to stand and sing Amhrán na bhFiann. In 2019, a club delegate in Westmeath, Mick Macken, voiced his concerns over 'the attitude of players all over the country to Amhrán na bhFiann. In hurling, they’re wearing their helmets right through it. They’re walking away before it finishes. It's the only country in the world that starts cheering about three quarters of the way through the national anthem’.

There are guidelines for how people should behave during the national anthem. The GAA has based their rules for the national anthem on guidelines outlined by the Seanad in 2018. These guidelines state that all persons present at the performance of Amhrán na bhFiann, should face the Irish flag and stand at attention and civilians, if applicable, should remove their headdress.

We need your consent to load this rte-player contentWe use rte-player to manage extra content that can set cookies on your device and collect data about your activity. Please review their details and accept them to load the content.Manage Preferences

From RTÉ Radio 1's Morning Ireland in 2018, Irish Sign Language interpreter Darren Byrne on performing the new ISL version of the National Anthem at the All-Ireland hurling final

The GAA's rules require that a three-minute and a one-minute reminder is given before the national anthem is played to allow all other officials to vacate the field. From a match presentation perspective, players breaking away before the end of the anthem and arriving onto the pitch late for the start of it has become an issue. To avoid players moving into their starting position as the anthem is played, referees have now been told not to start the game directly after it and allow at least 30 seconds for any team huddles or warm-ups before they are required to get into position for the start of the game.

One rule around the national anthem that is certainly not adhered to is the removal of helmets for the anthem's duration. The maximum fine for each breach of this rule is €700. It is extremely rare for hurlers to remove their helmets for the national anthem. It’s simply not practical to rush putting on a key piece of safety equipment in between the end of the anthem, assuming your position on the field of play and throw-in. So, whether it is players keeping their helmets on or fans drowning out the closing lines, acts of disobedience during the national anthem have no consequence at all, which creates a vicious cycle of rule violations. These rules are far too demanding and require a lot of effort for the GAA to effectively regulate.

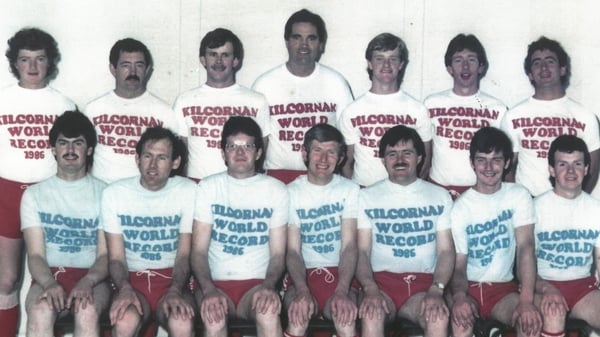

There are no documented rules on the national anthem in camogie or ladies Gaelic football. Arguably, women's Gaelic games are where the most disruption has been caused during the anthem in recent years. In 2023, intercounty camogie and football players sat down during Amhrán na bhFiann and wore t-shirts with the slogan '#UNITED FOR EQUALITY’ to outline frustration at the various organisations for the lack of development on a player welfare charter for inter-county players.

We need your consent to load this rte-player contentWe use rte-player to manage extra content that can set cookies on your device and collect data about your activity. Please review their details and accept them to load the content.Manage Preferences

From RTÉ Radio 1's Drivetime, author Rachel J. Cooper on why she wrote a book teaching children about our national anthem

In their opening game of the 2024 National Football League, the Dublin ladies team held up a banner during the national anthem, which caused many headlines and much applause for showing solidarity with the people of Palestine. The banner read 'Sos Cogadh sa Phalaistín' and called for a ceasefire in Palestine amid the ongoing conflict with Israel.

The national anthem is an ideal moment for protest as there is no work stoppage and the protests can highlight issues related to both sport and other concerns. During the National League in 2017, patrons were encouraged to show support for the installation of a 24/7 cardiac unit in University Hospital Waterford by putting their hand on their heart during the national anthem. Notification of the protests was given in the match day programmes, over the PA system, on social media and on local radio prior to the games. The activism occurred at several matches during the league campaign and was organised with media exposure in mind.

READ: Answering Ireland's call: Is it time for a new national anthem?

In 2016, GAA president Aogán Ó Fearghail commented that the GAA would be open to change in relation to the use of Amhrán na bhFiann and the Irish flag. The national anthem has become so entrenched as one of those goose bumps moments on big match days that it is impossible to contemplate an All-Ireland final without it. But there is no doubt that the national anthem is an empty gesture at many GAA fixtures.

There is a strong argument that the GAA has diluted the tradition to the point where the anthem is played hundreds of times each season and does nothing but create awkward moments owing to poor timing by players and back rooms, questionable renditions by singers and musicians and bad sound systems. Not to mention that the national anthem is an uncomfortable reminder for many of how patriotic symbols have been weaponised to undermine and diminish what being Irish means. Recent protests during the national anthem are the latest chapter in a long history between Amhrán na bhFiann and Gaelic games - a history that is powerful, complicated and controversial.

Follow RTÉ Brainstorm on WhatsApp and Instagram for more stories and updates

The views expressed here are those of the author and do not represent or reflect the views of RTÉ