A former guard at Stutthof concentration camp will go on trial in the northern German city of Hamburg on Thursday, in what could be one of the last criminal cases of an individual charged over the Holocaust.

The 93-year-old man, Bruno Dey, was 17 when he joined the SS-Totenkopfsturmbann (Death’s Head Battalion), which manned the watchtowers at the concentration camp east of what is now the city of Gdańsk, in Poland.

Between August 1944 and April 1945, Dey is accused of having been an accessory to the murder of 5,230 people. The figure includes 5,000 prisoners who fell victim to a typhus epidemic due to being denied access to food, water and medication as well as catastrophic hygiene conditions, 200 people who were gassed with Zyklon B and 30 people executed with a device specially built for killing with a shot in the neck.

By stopping prisoners from escaping, prosecutors argue the guards played a crucial role in allowing mass killings to take place at Stutthof, where an estimated 65,000 people perished before 9 May 1945, when the camp was liberated by allied forces.

The accused guard has cooperated with the investigators by allowing himself to be interviewed eight times. A doctor has declared him mentally fit for a trial, but each court session has been scheduled to last no more than two hours.

In one of the interviews, Dey reportedly confessed to having heard screams, and being aware of the nature of killings at the time. “I probably knew that these were Jews who hadn’t committed a crime, that they were only in here because they were Jews,” he said, according to Die Welt newspaper. “And they have a right to live and work freely like every other human being.”

Nonetheless, he reportedly does not believe he is guilty of being an accessory to murder. “What use would it have been if I had left, they would have found someone else?” Die Welt quoted him as saying.

The prosecution disagrees, arguing that especially by late 1944 it would have been possible for him to fight on the eastern front instead of serving as a guard. Dey claims to have been unable to go into battle because of a heart condition.

Stutthof, one of the smaller of the Nazi concentration camps, was originally set up to detain members of the Polish political leadership and intelligentsia, but was from 1944 increasingly used to hold and kill Jews transferred from the Baltic states, Hungary and the Auschwitz concentration camp. By the end of 1944, 70% of Stutthof’s population was Jewish.

The Hamburg trial has about 20 co-plaintiffs who spent time at Stutthof, of which four are former members of the Armia Krajowa (Home Army), the dominant resistance movement in Poland, and two are women who fought in the Warsaw uprising. Witnesses will fly in from America, Israel and Poland to give testimony in front of the court from the end of October.

Even though none of the witnesses are likely to remember Dey, the trial has a high symbolic value for many of the victims. “This is not a matter of revenge,” said Markus Horstmann, a lawyer representing one of the co-plaintiffs. “A trial like this is for them more about seeing what happened to them declared an injustice in a German court, and about telling their story so it doesn’t get forgotten,” he told the Guardian.

Germany’s criminal justice system has allowed a number of cases against concentration camp personnel such as that in Hamburg since the 2011 landmark sentencing of John Demjanjuk, a Ukrainian prisoner who became a “foreign helper” to the Nazis after his capture in 1942.

The trial against Demjanjuk ruled that someone could be sentenced for being a cog in the Nazi killing machine even if the prosecution could not link the accused to individual murders.

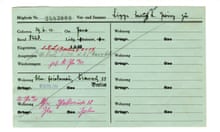

Since then, the Central Office for the Investigation of National Socialist Crimes, in Ludwigsburg, near Stuttgart, has been sifting through historical records in search of further cases to bring to trial. Dey came on to the radar of the centre’s researchers after they found his name in the archives of the Stutthof camp’s museum.

While prosecutors across Germany are carrying out preliminary investigations into a further 23 similar cases of Nazi crimes, the chances of these ending up in a court are rapidly decreasing with the passage of time, as the remaining suspects are all of extremely old age.

“We are continuously moving closer to the last trial of this kind,” a spokesperson told the Guardian.

Because Dey was 17 at the time of the alleged crimes, he will appear in front of a youth court, with the judge having to balance the severity of the crimes committed with German criminal law for young offenders, which has a maximum sentence of 10 years.