Richard Hugh Blackmore (born 14 April 1945) is an English guitarist. He was a founding member and the lead guitarist of Deep Purple, playing jam-style hard rock music that mixed guitar riffs and organ sounds.[1] He is prolific in creating guitar riffs and has been known for playing both classically influenced and blues-based solos.

Ritchie Blackmore | |

|---|---|

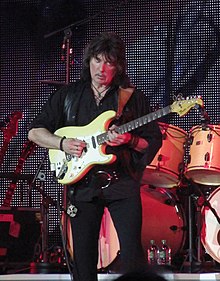

Blackmore performing in 2017 | |

| Background information | |

| Birth name | Richard Hugh Blackmore |

| Also known as | The Man in Black |

| Born | 14 April 1945 Weston-super-Mare, Somerset, England |

| Origin | Heston, Middlesex, England |

| Genres | |

| Occupations |

|

| Instruments | Guitar |

| Years active | 1960–present |

| Member of | Rainbow, Blackmore's Night |

| Formerly of | Deep Purple, The Outlaws |

| Spouses | Margit Volkmar

(m. 1964; div. 1969)Bärbel

(m. 1969; div. 1971)Amy Rothman

(m. 1981; div. 1983) |

| Website | blackmoresnight |

After leaving Deep Purple in 1975, Blackmore formed the hard rock band Rainbow,[2] which fused baroque music influences and elements of hard rock.[3][4] Rainbow steadily moved to catchy pop-style mainstream rock.[2] Rainbow broke up in 1984 with Blackmore re-joining Deep Purple until 1993. In 1997, he formed the traditional folk rock project Blackmore's Night along with his current wife Candice Night, shifting to vocalist-centred sounds.

As a member of Deep Purple, Blackmore was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in April 2016.[5] He is cited by publications such as Guitar World and Rolling Stone as one of the greatest and most influential guitar players of all time.[6][3]

Early life

editBlackmore was born at Allendale Nursing Home in Weston-super-Mare, Somerset, as second son to Lewis J. Blackmore and Violet (née Short). The family moved to Heston, Middlesex, when Blackmore was two. He was 11 when he was given his first guitar by his father on certain conditions, including learning how to play properly, so he took classical guitar lessons for one year.[7]

In an interview with Sounds magazine in 1979, Blackmore said that he started the guitar because he wanted to be like British musician Tommy Steele, who used to just jump around and play. Blackmore loathed school and hated his teachers.[8] He said he would always get caned for speaking in class, which traumatized him to the point he had difficulty in talking to people in subsequent years. Blackmore also became disillusioned with education, thinking that if he were to excel in his studies, he would end up being like his teachers.[9]

Blackmore left school at age 15 and started work as an apprentice radio mechanic at nearby Heathrow Airport. He took electric guitar lessons from session guitarist Big Jim Sullivan.

Career

edit1960s

editIn 1960, he began to work as a session player for Joe Meek's music productions and performed in several bands. He was initially a member of the instrumental band the Outlaws, who played in both studio recordings and live concerts and like many bands of the era, used other names (such as The Rally Rounders and The Chaps) to secure multiple repeat gigs. Otherwise, in mainly studio recordings, he backed singer Glenda Collins, German-born pop singer Heinz (playing on his top ten hit "Just Like Eddie" and "Beating Of My Heart"), and others.[10] Thereafter, in mainly live concerts, he backed horror-themed singer Screaming Lord Sutch, beat singer Neil Christian, and others.[11]

Blackmore joined a band-to-be called Roundabout in late 1967 after receiving an invitation from Chris Curtis while living in Hamburg and arriving at the Curtis flat to be greeted by Curtis’ flatmate, Jon Lord. Curtis originated the concept of the band, but would be forced out before the band fully formed. After the line-up for Roundabout was complete in April 1968, Blackmore is credited with suggesting the new name Deep Purple, as it was his grandmother's favourite song.[12] Deep Purple's early sound leaned on psychedelic and progressive rock,[13] but also included cover versions of 1960s pop songs.[14] This "Mark One" line-up featuring singer Rod Evans and bass player Nick Simper lasted until mid-1969 and produced three studio albums. During this period, organist Jon Lord appeared to be the leader of the band,[13] and wrote much of their original material.[15]

1970s

editThe first studio album from Purple's second line-up, In Rock (1970), signalled a transition in the band's sound from progressive rock to hard rock, with Blackmore and Lord having heard bands such as Vanilla Fudge and albums such as Led Zeppelin II and King Crimson's debut album.[4] This "Mark Two" line-up featuring rock singer Ian Gillan and bassist Roger Glover lasted until mid-1973, producing four studio albums (two of which reached No. 1 in the UK), and one live double album. During this period, the band's songs primarily came out of their jam sessions, so songwriting credits were shared by the five members.[1] Blackmore later stated, "I didn't give a damn about song construction. I just wanted to make as much noise and play as fast and as loud as possible."[16]

Guitarist Steve Vai was more complimentary about Blackmore's role in developing song ideas: "He was able to bring blues to rock playing unlike anybody else."[17]

The third Deep Purple line-up featured David Coverdale on vocals and Glenn Hughes on bass and vocals. Songwriting was now more fragmented, as opposed to the band compositions from the Mark Two era. This "Mark Three" line-up lasted until mid-1975 and produced two studio albums and one live album . Blackmore quit the band to front a new group, Rainbow. In 1974, Blackmore took cello lessons from Hugh McDowell (of ELO).[18] Blackmore later stated that when playing a different musical instrument, he found it refreshing because there is a sense of adventure not knowing exactly what chord he's playing or what key he is in.[19]

Blackmore originally planned to make a solo album, but instead in 1975 formed his own band, Ritchie Blackmore's Rainbow, later shortened to Rainbow. Featuring vocalist Ronnie James Dio and his blues rock backing band Elf as studio musicians, this first line-up never performed live. The band's debut album, Ritchie Blackmore's Rainbow, was released in 1975. Rainbow was originally thought to be a one-off collaboration, but endured as an ongoing band project with a series of album releases and tours. Rainbow's music was partly inspired by elements of medieval and baroque music[4][20][21] since Blackmore started to play cello for musical composition.[16][19] During this period, Blackmore wrote a crucial part of Dio's basic melodies, particularly on their debut album.[22] Shortly after the first album was recorded, Blackmore recruited new backing musicians to record the second album Rising (1976), and the following live album, On Stage (1977). Rising was originally billed as "Blackmore's Rainbow" in the US.[23] After the next studio album's release and supporting tour in 1978, Dio left Rainbow due to "creative differences" with Blackmore, who desired to move in a more commercial sounding direction.[24]

Blackmore continued with Rainbow, and in 1979 the band released a new album titled Down To Earth, which featured R&B singer Graham Bonnet. During song composition, Bonnet says that he wrote his vocal melodies based upon the lyrics of bassist Roger Glover.[25] The album marked the commercialisation of the band's sound and contained their first smash hit with the single "Since You Been Gone" (penned by Russ Ballard).[26]

1980s

editThe next Rainbow album, Difficult to Cure (1981), introduced melodic vocalist Joe Lynn Turner. The instrumental title track from this album was an arrangement of Beethoven's Ninth Symphony with additional music. Blackmore once said, "I found the blues too limiting, and classical was too disciplined. I was always stuck in a musical no man's land."[3] The album marked the further commercialisation of the band's sound with Blackmore describing at the time a liking for the AOR band, Foreigner.[27] The music was consciously radio-targeted in a more AOR style,[28] resulting in some degree of alienation with many of Rainbow's earlier fans.[2] Rainbow's next studio album was Straight Between the Eyes (1982) and included the hit single "Stone Cold". It would be followed by the album Bent Out of Shape (1983), which featured the single "Street of Dreams". In 1983, Rainbow were also nominated for a Grammy Award for the Blackmore-penned instrumental ballad track "Anybody There".[29] Rainbow disbanded in 1984. A then-final Rainbow album, Finyl Vinyl, was patched together from live tracks and the B-sides of various singles.

In 1984, Blackmore joined a reunion of the former Deep Purple "Mark Two" line-up and recorded new material. This reunion line-up lasted until 1993,[30] producing three studio albums and one live album. Although the reunion's first album Perfect Strangers (1984) saw chart success, the second studio album The House of Blue Light (1987) displayed a sound that was closer to Rainbow's music and did not sell as well. The album's musical style differed from the traditional Purple sound due to Blackmore's Rainbow background, which distinguished him from the other members.[31]

1990s

editThe next Deep Purple line-up recorded one album titled Slaves and Masters (1990), which featured former Rainbow vocalist Joe Lynn Turner. During song composition, Turner wrote his vocal melodies.[16] Subsequently, the "Mark Two" line-up reunited for a second time in late 1992 and produced one studio album, The Battle Rages On.... Overall, the traditional Deep Purple sound returned.[32] During the follow-up promotional tour, Blackmore quit the band for good in November 1993. Prominent guitarist Joe Satriani was brought in to complete the remaining tour dates.

Blackmore reformed Rainbow with new members in 1994. This Rainbow line-up, featuring hard rock singer Doogie White, lasted until 1997 and produced one album titled Stranger in Us All in 1995. It was originally intended to be a solo album but due to the record company pressures the record was billed as Ritchie Blackmore's Rainbow.[33] Though Doogie White wasn't as distinctive as previous Rainbow singers, the album had a sound dissimilar to any Rainbow of old.[28] This was Rainbow's eighth studio album, made after a gap of 12 years since Bent out of Shape, and is regarded as Blackmore's last hard rock album. A world tour including South America followed.[29] Rainbow was disbanded once again after playing its final concert in 1997. Blackmore later said, "I didn't want to tour very much."[34]

Over the years Rainbow went through many personnel changes with no two studio albums featuring the same line-up: Blackmore was the sole constant band member.[26] Rainbow achieved modest success; the band's worldwide sales are estimated at more than 28 million album copies, including 4 million copies sold in the US.[35]

In 1995, Blackmore, with his girlfriend Candice Night as vocalist, began working on a more traditional folk rock project, which later became the debut album Shadow of the Moon (1997) for their duo Blackmore's Night.[28] Blackmore once portrayed their artistic characteristics as "Mike Oldfield plus Enya".[33] Blackmore mostly used acoustic guitar,[33] to back Night's delicate vocal melodies, which he often wrote.[36] Night said, "When he sings, he sings only for me, in private".[37] As a result, his musical approach shifted to vocalist-centred sounds, and their recorded output is a mixture of original and cover materials. The band's musical style is heavily inspired by medieval music blended with Night's lyrics, which often feature themes of love and medieval times. The second release, entitled Under a Violet Moon (1999) continued in the same folk-rock style, with Night's vocals remaining a prominent feature of the band's style. The title track's lyrics were partly written by Blackmore. "Violet" was his mother's first name and "Moon" was his grandmother's surname.[34]

2000s–present

editIn subsequent albums, particularly Fires at Midnight (2001) which featured the Bob Dylan song "The Times They Are a Changin'", there was occasionally an increased incorporation of electric guitar into the music, whilst maintaining a basic folk rock direction. A live album, Past Times with Good Company was released in 2002. After the next studio album's release, an official compilation album Beyond the Sunset: The Romantic Collection was released in 2004, featuring music from the four studio albums. A Christmas-themed holiday album, Winter Carols was released in 2006. Through numerous personnel changes, the duo has utilized over 26 backing musicians on their releases.[38] Blackmore sometimes played drums in recording studio.[34][39] They choose to avoid typical rock concert tours, instead limiting their appearances to small intimate venues.[40] In 2011, Night said, "We have actually turned down a lot of (touring) opportunities."[41] They have released eleven studio albums, with the latest one being Nature's Light in 2021.

A re-formed Rainbow performed three European concerts in June 2016. The concert setlists included both Rainbow and Deep Purple material. The band featured metal singer Ronnie Romero, keyboardist Jens Johansson and bassist Bob Nouveau.[42]

Equipment

editDuring the 1960s, Blackmore played a Gibson ES-335 but from 1970 he mainly played a Fender Stratocaster until he formed Blackmore's Night in 1997. The middle pick-up on his Stratocaster is screwed down and not used. Blackmore occasionally used a Fender Telecaster Thinline during recording sessions. He is also one of the first rock guitarists to use a "scalloped" fretboard which has a "U" shape between the frets.

In the 1970s, Blackmore used a number of different Stratocasters; one of his main guitars was an Olympic white 1974 model with a rosewood fingerboard that was scalloped.[43] Blackmore added a strap lock to the headstock of this guitar as a conversation piece to annoy and confuse people, as it didn't actually do anything.[44]

His amplifiers were originally 200-Watt Marshall Major stacks which were modified by Marshall with an additional output stage (generating about 27 dB)[citation needed] to make them sound more like Blackmore's favourite Vox AC30 amp cranked to full volume. Since 1994, he has used ENGL tube amps.

Effects he used from 1970 to 1997, besides his usual tape echo, included a Hornby Skewes treble booster in the early days. Around late-1973, he experimented with an EMS Synthi Hi Fli guitar synthesizer. He sometimes used a wah-wah pedal and a variable control treble-booster for sustain, and Moog Taurus bass pedals were used in solo parts during concerts. He also had a modified Aiwa TP-1011 tape machine built to supply echo and delay effects; the tape deck was also used as a pre-amp.[43] Other effects that Blackmore used were a Uni-Vibe, a Dallas Arbiter Fuzz Face and an Octave Divider.

In the mid-1980s, he experimented with Roland guitar synthesizers. A Roland GR-700 was seen on stage as late as 1995–96, later replaced with the GR-50.

Blackmore has experimented with many different pick-ups in his Strats. In the early Rainbow era, they were still stock Fender equipment, but later became Dawk-installed over wound, dipped, Fender pick-ups. He has also used Schecter F-500-Ts, Velvet Hammer "Red Rhodes", DiMarzio "HS-2", OBL "Black Label", and Bill Lawrence L-450, XL-250 (bridge), L-250 (neck) pick-ups. In his signature Stratocaster, Seymour Duncan Quarter Pound Flat SSL-4's are used to emulate the Schecter F500ts. Since the early 1990s, he has used Lace Sensor (Gold) "noiseless" pick-ups.

Influences and tastes

editIn the first issue of International Musician and Recording World, Blackmore named Jeff Beck his favorite guitar player. He also sang praises for Jimi Hendrix, Yes guitarist Steve Howe, Bob Dylan sideman Mike Bloomfield and Tommy Bolin, who would soon take his place on Deep Purple.[45][46][47] Still on the subject of Beck, he said:

Being a guitarist, I obviously know a lot of tricks of the trade, but whenever I watch Beck I think "How the hell is he doing that?" Echoes suddenly come from no-where; he can play a very quiet passage with no sustain and in the next second suddenly race up the fingerboard with all this sustain coming out. He seems to have sustain completely at his fingertips, yet he doesn't have it all the time, only when he wants it.[45]

Blackmore credits fellow guitarist Eric Clapton's music with helping him develop his own style of vibrato around 1968 or 1969.[48]

In 1979,[8] Blackmore said: "I like popular music. I like ABBA very much. But there's so much stigma like, 'you can't do this because you're a heavy band', and I think that's rubbish. You should do what you want ... I think classical music is very good for the soul. A lot of people go 'ah well, classical music is for old fogies' but I was exactly the same. At 16 I didn't want to know about classical music: I'd had it rammed down my throat. But now I feel an obligation to tell the kids 'look, just give classical music a chance' ... the guitar frustrates me a lot because I'm not good enough to play it sometimes so I get mad and throw a moody. Sometimes I feel that what I'm doing is not right, in the sense that the whole rock and roll business has become a farce, like Billy Smart, Jr. Circus, and the only music that ever moves me is very disciplined classical music, which I can't play. But there's a reason I've made money. It's because I believe in what I'm doing, in that I do it my way—I play for myself first, then secondly the audience—I try to put as much as I can in it for them. Lastly I play for musicians and the band, and for critics not at all."

Artistry

editBlues origins

editIn his soloing, Blackmore combines blues scales and phrasing with dominant minor scales and ideas from European classical music. While playing he would often put the pick in his mouth, playing with his fingers.[49]

Classical influence

editBlackmore is notoriously appreciative of classical music, and is noted as "the" pioneer in bringing to rock 'n' roll. He is particularly fond of Baroque composer Johann Sebastian Bach. For instance, he revealed to Guitar World that he used a Bachian chord progression – Bm, Db, C, G – behind the "Highway Star" guitar solo.[50]

Another cue Blackmore took from classical music was his penchant for "exotic" scales. Along with former Scorpions "axemen" Uli Jon Roth and Michael Schenker, Blackmore pioneered the use of the harmonic minor scale in the 1970s, effectively laying the groundwork for neoclassical metal. The harmonic minor would become Yngwie Malmsteen's scale of choice in the 1980s.[51][52] Blackmore also used the Gypsy scale on Rainbow's "Gates of Babylon".[53]

Ritchie Blackmore was also keen in using the cycle of 4ths chord progressions, by the way of triad arpeggios. This was standard practice in Baroque music, especially by Bach.[51][54] A notable example is the second half of the "Burn" solo.[55]

Rhythm guitar

editOne of Ritchie Blackmore hallmarks is the ability to writing memorable riffs using 4rths. His most iconic riff - the intro to Deep Purple's "Smoke On the Water" - is an example of such. Other Deep Purple songs that used the same idea were "Mandrake Root" and "Burn", along with Rainbow's "Man On A Silver Mountain", "All Night Long" and "Long Live Rock ‘n’ Roll".[51] Riffs in 4rths became a mainstay in hard rock and heavy metal, post-Blackmore. Notable examples include Judas Priest's "Hell Bent for Leather",[56] Ozzy Osbourne's "Suicide Solution",[57] Mötley Crüe's "Shout at the Devil" and Iron Maiden's "Two Minutes to Midnight".[58]

Blackmore frequently does sparse verse arrangements, using single-note riffs or playing octaves and their respective basslines. Such accompaniments give room to keyboard players.[51] "Smoke On the Water" is a prime example of this technique.[59]

Blackmore is also known for unapologetically borrowing musical ideas from other artist's music. "I get inspired by other people's songs and write something vaguely similar", said he on a 1978 Guitar Player interview.[60] Here's a brief list:

- Although penned as a Deep Purple original, Ritchie Blackmore actually learnt "Mandrake Root"'s melody and chord progression through Carlos Little, his Screaming Lord Sutch & the Savages bandmate. It was written by previous Savages guitarist Bill Parkinson and originally called "Lost Soul".[61]

- The "Black Night" intro riff is partially borrowed from the verse of Ricky Nelson's 1962 version of "Summertime", originally written by George and Ira Gershwin.[62]

- In Rock opener "Speed King" was based on two Hendrix singles, "Stone Free" (1966) and "Fire" (1967).[62]

- The "Lazy" track from Machine Head was inspired by Cream's "Steppin' Out".[62]

- "Burn"'s main riff is similar to George Gershwin's 1924 song "Fascinating Rhythm".[63]

- Another track from the Burn album – "Mistreated" – was admittedly molded on Free's "Heartbreaker", from the band's 1973 album.[60]

Solo guitar

editIntroduced by jazz musicians Les Paul, Barney Kessel and Tal Farlow in the 1950s, sweep picking was first used in a rock context by Ritchie Blackmore. It can be heard in the tail end of "April", the final track from Deep Purple's homonymous album. Blackmore used the technique again on Rainbow's "Kill the King". Fusion virtuoso Frank Gambale would perfect it in the 1980s.[64]

Ritchie Blackmore is known for switching between different keys and modes in the same solo. YouTuber and musician Rick Beato pointed out that, on "Smoke on the Water"'s solo section, Blackmore suddenly switches from a G minor blues scale to a C dorian on a rapid descending scale run. In his words, this sudden change "works over it, but it's kind of weird."[65] Lick Library's Danny Gill also praises Blackmore work on this solo, pointing out that it "displays his mastery over modal playing, with a clever mix of Dorian and Mixolydian modes." The solo from Rainbow's "Man on the Silver Mountain" also transitions between modes, from a major to a blues scale.[66]

Personal life

editIn May 1964, Blackmore married Margit Volkmar (b. 1945) from Germany.[67] They lived in Hamburg during the late 1960s.[68] Their son, Jürgen (b. 1964), played guitar in the touring tribute band Over the Rainbow. Following their divorce, Blackmore married Bärbel, a former dancer from Germany, in September 1969[69][70] until their divorce in the early 1970s. As a result, he is a fluent German speaker.[68]

For tax reasons, he moved to the US in 1974.[71][72] Initially he lived in Oxnard, California,[4] with opera singer Shoshana Feinstein for one year.[73] She provided backing vocals on two songs in Rainbow's first album. During this period, he listened to early European classical music and light music a lot, for about three-quarters of his private time. Blackmore once said, "It's hard to relate that to rock. I listen very carefully to the patterns that Bach plays. I like direct, dramatic music."[4] After having an affair with another woman, Christine, Blackmore met Amy Rothman in 1978,[74] and moved to Connecticut.[75] He married Rothman in 1981,[76] but they divorced in 1983. Following the marriage's conclusion, he began a relationship with Tammi Williams.[77] In early 1984 Blackmore met Williams in Chattanooga, Tennessee, where she was working as a hotel employee. In the same year, he purchased his first car, having learned to drive at 39 years of age.[78]

Blackmore and then-fashion model Candice Night began living together in 1991. They moved to her native Long Island in 1993.[79][failed verification] Having been engaged for nearly 15 years,[80] the couple married in 2008.[81] Night said, "he's making me younger and I'm aging him rapidly."[82] Their daughter Autumn was born on 27 May 2010,[83][84] and their son Rory on 7 February 2012.[22][39] Blackmore is a heavy drinker [22] and watches German-language television on his satellite dish when he is at home.[68] He has several German friends[68] and a collection of about 2,000 CDs of Renaissance music.[68][83]

Ritchie claimed in an interview that he's spiritual, but not religious, saying that "religion usually involves money".[85]

Legacy

editReaders of Guitar World voted two of Blackmore's guitar solos (both recorded with Deep Purple) among the 100 Greatest Guitar Solos of all time – "Highway Star" ranked 19th, and "Lazy" ranked 74th.[86] His solo on "Child in Time" was ranked no. 16 in a 1998 Guitarist magazine readers poll of Top 100 Guitar Solos of All-Time.[87] On 8 April 2016, he was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame as one of original members of Deep Purple; he did not attend the ceremony.[88][89][90]

In 1993, musicologist Robert Walser defined him as "the most important musician of the emerging metal/classical fusion".[91] He is credited as a precursor of the so-called "guitar shredders" that emerged in the mid-1980s.[92]

Blackmore has been an influence on several 1980s guitarists such as Akira Takasaki, Fredrik Åkesson,[93] Brett Garsed,[94] Janick Gers,[95] Paul Gilbert,[96] Craig Goldy,[97] Scott Henderson,[98] Dave Meniketti,[99] Randy Rhoads,[100] Michael Romeo,[101] Wolf Hoffmann,[102] Billy Corgan,[103] Lita Ford,[104] Brian May,[105] Phil Collen[106] and Yngwie Malmsteen.[107] For his part Metallica drummer Lars Ulrich, who praised Blackmore on numerous occasions, highlighted that his "wild stage presence" led him to buy Deep Purple's Fireball, his first album ever.[108] The drummer also claimed that the guitarist's riffs from his time with Rainbow had a significant impact on Metallica.[109] Swedish guitarist Yngwie Malmsteen acknowledged having been early on influenced by Blackmore;[110] during his childhood he learned to play Fireball in its entirety. He even dressed like him onstage.[111] Malmsteen also hired three Rainbow vocalists for his band; Joe Lynn Turner, Graham Bonnet and Doogie White.[112]

He was portrayed by Mathew Baynton in the 2009 film Telstar.

Discography

editThis section of a biography of a living person does not include any references or sources. (August 2020) |

Session recordings (1960–1968)edit

|

Previously unreleased outtakesedit

Compilationsedit

Select guest appearancesedit

|

References

edit- ^ a b "A Highway Star: Deep Purple's Roger Glover Interviewed". The Quietus. 20 January 2011.

- ^ a b c Rivadavia, Eduardo. "Rainbow". Allmusic. Retrieved 8 July 2010.

- ^ a b c "The 100 Greatest Guitarists of All Time". Rolling Stone. 22 November 2011. Retrieved 18 November 2013.

- ^ a b c d e Rosen, Steven (1975). "Ritchie Blackmore Interview: Deep Purple, Rainbow and Dio". Guitar International. Archived from the original on 22 December 2011.

- ^ "Deep Purple Rocks Hall of Fame With Hits-Filled Set" Archived 6 May 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Rolling Stone. Retrieved 24 July 2016

- ^ Olsen, Eric (1 February 2004). "Guitar World's "100 Greatest Metal Guitarists of All Time"". blogcritics. Archived from the original on 5 June 2011. Retrieved 30 May 2009.

- ^ Korner, Alexis (6 March 1983). "Interview with Ritchie Blackmore". BBC Radio One Guitar Greats series.

- ^ a b Sounds, 15 December 1979

- ^ Blackmore, Ritchie (16 August 2022). "Ritchie Blackmore – On School And Parents (The Ritchie Blackmore Story, 2015)". YouTube. Retrieved 17 August 2023.

- ^ "Discography". The Official Ritchie Blackmore and Blackmore's Night website. Archived from the original on 16 August 2011. Retrieved 3 April 2013.

- ^ "Ritchie Blackmore bands and sessions". thehighwaystar.com. Retrieved 3 April 2013.

- ^ Tyler, Kieron On The Roundabout With Deep Purple Retrieved 31 August 2020

- ^ a b Browne, David. "Deep Purple early years: Seventy Seven Minutes In Prog Rock Heaven". deep-purple.net. Retrieved 19 January 2011.

- ^ van der Lee, Matthijs (1 October 2009). "Shades of Deep Purple". Sputnik Music.

- ^ van der Lee, Matthijs (2 October 2009). "The Book of Taliesyn". Sputnik Music.

- ^ a b c Kleidermacher, Mordechai (February 1991). "When There's Smoke.. THERE'S FIRE!". Guitar World.

- ^ "STEVE VAI ON RITCHIE BLACKMORE – "HE WAS ABLE TO BRING BLUES TO ROCK PLAYING UNLIKE ANYBODY ELSE"". 28 June 2021.

- ^ "RAINBOW: 1974–1976". The Ronnie James Dio Web Site. Retrieved 22 September 2011.

- ^ a b Warnock, Matt (28 January 2011). "Ritchie Blackmore: The Autumn Sky Interview". Guitar International Magazine. Archived from the original on 1 February 2011.

- ^ "Ritchie Blackmore". Guitarists. Archived from the original on 23 July 2011. Retrieved 2 July 2012.

- ^ Kent-Abbott, David. "Ritchie Blackmore's Rainbow". Allmusic. Retrieved 4 May 2013.

- ^ a b c "Blackmore's Night interview". Burrn! Magazine. 5 June 2013.

- ^ "Blackmore's Rainbow – Rainbow Rising". Discogs.com. 1984. Retrieved 26 December 2011.

- ^ Bloom, Jerry (2006). "Chapter 11 – Down To Earth (1978–1980)". Black Knight: Ritchie Blackmore. Omnibus press. p. 226. ISBN 9780857120533.

- ^ "GRAHAM BONNET Talks RAINBOW, MSG And ALCATRAZZ in New Interview". blabbermouth.net. 19 November 2010. Archived from the original on 21 November 2010.

- ^ a b Frame, Pete (March 1997). "Rainbow Roots and Branches." The Very Best of Rainbow (liner notes).

- ^ In an interview in Sounds (25 July 1981), a UK music paper

- ^ a b c Adams, Bret. "Stranger in Us All". Allmusic. Retrieved 22 July 2010.

- ^ a b "Ritchie's Bio". The Official Ritchie Blackmore and Blackmore's Night website. Archived from the original on 18 October 2010. Retrieved 30 December 2010.

- ^ Luhrssen, David; Larson, Michael (24 February 2017). Encyclopedia of Classic Rock. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-4408-3514-8.

- ^ Rivadavia, Eduardo. "The House of Blue Light review". AllMusic. Rovi Corporation. Retrieved 17 September 2011.

- ^ Ruhlmann, William. "The Battle Rages On". Allmusic. Retrieved 12 March 2013.

- ^ a b c Adams, Bret. "Blackmore's Night". Allmusic. Retrieved 28 April 2011.

- ^ a b c Bloom, Jerry (2006). "Chapter 16: Play Minstrel Play (1997–2000)". Black Knight: Ritchie Blackmore. Omnibus press. ISBN 9780857120533.

- ^ Alan, Mark (5 October 2012). "Rainbow Featured on 80's at 8 With "Stone Cold"". 103.7 The Loon.

- ^ Night, Candice (November 2002). "Between Us – November 2002". Candice Night Official Website. Archived from the original on 14 December 2002.

- ^ Night, Candice (August 2003). "Between Us August 2003". Candice Night Official Website. Archived from the original on 7 August 2003.

- ^ "BLACKMORE'S NIGHT". MusicMight. Archived from the original on 28 January 2012. Retrieved 22 September 2011.

- ^ a b DuRussel, Mick (28 October 2009). "candice of blackmore's night". SpotonLI.

- ^ Hill, Gary; Damigella, Rick; Toering, Larry. "Interview with Candice Night of Blackmore's Night from 2010". MusicStreetJournal.

- ^ Christian A. (7 January 2011). "Blackmore's Night – Candice Night (vocals)". SMNnews. Archived from the original on 11 September 2011. Retrieved 22 December 2011.

- ^ "Ritchie Blackmore's Rainbow: First Official Photo Of 2016 Lineup". .blabbermouth. 16 March 2016.

- ^ a b Rainbow (2006). Live in Munich 1977 (DVD). Audio commentary.

- ^ "Ritchie Blackmore Gear Videos". Guitarheroesgear.com. Archived from the original on 2 April 2010. Retrieved 13 November 2010.

- ^ a b Tiven 1975, p. 6.

- ^ Tiven 1975, p. 7.

- ^ Rolli, Bryan (3 June 2024). "Ritchie Blackmore explains how boredom led to Deep Purple exit". Ultimate Classic Rock. Retrieved 2 September 2024.

- ^ "Ritchie Blackmore, Interviews". Thehighwaystar.com. Retrieved 12 May 2019.

- ^ Barrett, Richard (6 August 2021). "How to play blues like Ritchie Blackmore". Guitarist. Retrieved 19 October 2024.

- ^ Webb, Martin K. (19 April 2024). ""The chord progression in the Highway Star solo – Bm, to a Db, C, and then G – is a Bach progression": Ritchie Blackmore on Steve Howe, Jimi Hendrix, classical influences and more". GuitarPlayer.com. Retrieved 3 September 2024.

- ^ a b c d Hilborne, Phil (31 December 2018). "5 guitar tricks you can learn from Ritchie Blackmore". MusicRadar. Retrieved 28 September 2024.

- ^ Guitar Player Staff (1 September 2023). "John McLaughlin, Al Di Meola, Marty Friedman and Yngwie Malmsteen Didn't Rely Exclusively on Western Scales – so Why Should You?". GuitarPlayer.com. Retrieved 28 September 2024.

- ^ Guitar Player Staff (17 May 2019). "Around the World in Seven Scales". Guitar World. Retrieved 12 October 2024.

- ^ Aledort, Andy (14 January 2019). "Arpeggio Studies Based on the Cycle of Fourths". Guitar World. Retrieved 1 October 2024.

- ^ Billmann, Pete; Scharfglass, Matt (1998). The Best of Deep Purple. Miwaukee, WI: Hal Leonard. p. 12. ISBN 0793591929.

- ^ Gress, Jesse (1990). Judas Priest – Vintage Hits. Milwaukee, WI: Hal Leonard Publishing Corporation. p. 56. ISBN 9789990590319.

- ^ Marshall, Wolf (1987). Ozzy Osbourne – Randy Rhoads Tribute. Port Chester, NY: Cherry Lane Music. p. 77. ISBN 9780895243478.

- ^ Booth, Addi; Pappas, Paul (2006). Iron Maiden – Anthology. Milwaukee, WI: Hal Leonard Publishing Corporation. p. 161. ISBN 9780634066900.

- ^ Billmann, Pete; Scharfglass, Matt (1998). The Best of Deep Purple. Miwaukee, WI: Hal Leonard. p. 122. ISBN 0793591929.

- ^ a b Rosen, Steven (September 1978). "Ritchie Blackmore: From Deep Purple to Rainbow". Guitar Player. Retrieved 6 October 2024.

- ^ Bloom, Jerry (2006). Black Knight: Ritchie Blackmore. London: Omnibus Press. p. 94. ISBN 9781846092664.

- ^ a b c Starkey, Arun (28 May 2022). "The Deep Purple riffs Ritchie Blackmore admitted he pinched". Far Out. Retrieved 6 October 2024.

- ^ McDowell, Jay. "The Meaning Behind the Witchy Woman in Deep Purple's "Burn"". American Songwriter. Retrieved 6 October 2024.

- ^ Griffiths, Charlie (6 April 2020). "Sweep picking: how to get started with this awe-inspiring guitar technique". Guitar World. Retrieved 30 September 2024.

- ^ Beato, Rick (9 October 2023). "What Makes This Song Great? "Smoke On The Water" Deep Purple". Retrieved 19 October 2024 – via YouTube.

- ^ Gill, Danny. "Learn To Play Ritchie Blackmore – The Solos". Lick Library. Retrieved 19 October 2024.

- ^ "BIO". Official Site of J. R. Blackmore. Archived from the original on 17 June 2010. Retrieved 24 May 2010.

- ^ a b c d e Night, Candice (June 2004). "Between Us June 2004". Candice Night Official Website. Archived from the original on 5 June 2004.

- ^ "Events 1969". Sixties City. Archived from the original on 30 March 2010. Retrieved 24 May 2010.

- ^ "A short story about Ritchie Blackmore and his long forgotten 1961 Gibson ES-335". Me and My Guitar. 10 April 2011.[unreliable source?]

- ^ Crowe, Cameron (10 April 1975). "Ritchie Blackmore: Shallow Purple". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 2 September 2018.

- ^ Crowe, Cameron (10 April 1975). "Rolling Stone #184: Ritchie Blackmore". Theuncool.com. Retrieved 2 September 2018.

The tax people have gone berserk over us. They're really trying to skim us. We've all moved out of England. – Blackmore

- ^ Bloom, Jerry (2006). "Chapter 8: The Black Sheep of the Family (1973–1975)". Black Knight: Ritchie Blackmore. Omnibus press. ISBN 9781846097577.

- ^ Bloom, Jerry (2006). "Chapter 10: Down to Earth (1978–1980)". Black Knight: Ritchie Blackmore. Omnibus press. p. 240. ISBN 978-1846092664.

- ^ Bloom, Jerry (2006). "Chapter 10: Down to Earth (1978–1980)". Black Knight: Ritchie Blackmore. Omnibus press. p. 227. ISBN 978-1846092664.

- ^ "DPAS Magazine Archive. Darker Than Blue, 1981". Retrieved 24 May 2010.

- ^ Bloom, Jerry (2006). "Chapter 14: The Battele Rages on And On ... (1990–1993)". Black Knight: Ritchie Blackmore. Omnibus press. p. 291. ISBN 9780857120533.

- ^ Bloom, Jerry (2006). "Chapter 12: The End of the Rainbow (1980–84)". Black Knight: Ritchie Blackmore. Omnibus press. ISBN 9781846097577.

- ^ Night, Candice (June 2011). "Between Us June 2011". Candice Night Official Website. Retrieved 20 October 2011.

- ^ Night, Candice (July 2006). "Between Us July 2006". Candice Night Official Website. Retrieved 24 May 2010.

- ^ "RITCHIE BLACKMORE, Longtime Girlfriend CANDICE NIGHT Tie The Knot". Blabbermouth.net. 13 October 2008. Archived from the original on 6 June 2011. Retrieved 24 May 2010.

- ^ "Candice Night and Ritchie Blackmore". New York DAILY NEWS. 28 December 2008. Archived from the original on 10 August 2011.

- ^ a b Trunk, Russell A. (February 2011). "Blackmore's Night". Exclusive Magazine.

- ^ "RITCHIE BLACKMORE And CANDICE NIGHT Announce Arrival of First Child, Autumn Esmerelda". Retrieved 26 July 2010.

- ^ "Ritchie Blackmore: I'm a Spiritual Man, Not a Religious Man. Religion Usually Revolves Around Money".

- ^ "Guitar World 100 Greatest Guitar Solos". about.com. Retrieved 25 March 2010.

- ^ "Rocklist.net...Guitar Lists..." Rocklistmusic.co.uk. Retrieved 14 April 2022.

- ^ "Rock Hall 2016: Lars Ulrich, Deep Purple praise guitarist Ritchie Blackmore". cleveland.com. 8 April 2016. Retrieved 26 November 2016.

- ^ "Ritchie Blackmore Honored At Rock & Roll Hall Of Fame Induction, Despite Snub By Current Deep Purple Members". inquisitr.com. 9 April 2016. Retrieved 26 November 2016.

- ^ "Ritchie Blackmore comments on Deep Purple Rock Hall induction". hennemusic.com. 11 April 2016. Retrieved 26 November 2016.

- ^ Robert Walser, Running with the Devil: Power, Gender, and Madness in Heavy Metal Music, Wesleyan University Press, 1993, p.63-64

- ^ Pete Prown, Harvey P. Newquist, Legends of Rock Guitar: The Essential Reference of Rock's Greatest Guitarists, Hal Leonard Corporation, 1997, p.65

- ^ Monoxide, Carmen (7 December 2011). "Interview with Opeth lead guitarist Fredrik Åkesson". puregrainaudio.com.

- ^ "Interview with Brett Garsed on the Heels of his "Dark Matter" Release". guitaristnation.com. Archived from the original on 3 November 2013.

- ^ Mick Wall, Iron Maiden: Run to the Hills, the Authorised Biography, Sanctuary Publishing, 2004, p.277

- ^ Richman (18 May 2013). "Paul Gilbert interview". guitarmania.eu.

- ^ dreffett. "Interview: Guitarist Craig Goldy Talks Working with Ronnie James Dio and Touring with Dio's Disciples, 3/14/2013". guitarworld.com.

- ^ "JGS Scott Henderson Interview, 12/20/12". jazzguitarsociety.com.

- ^ "Dave Meniketti interview". guitar.com. 14 December 2012.

- ^ Hall, Russell (24 October 2012). "Interview with Randy Rhoads' Biographer". gibson.com. Archived from the original on 14 July 2018. Retrieved 2 November 2013.

- ^ Edwards, Owen (3 April 2008). "Michael Romeo Interview – A Perfect Symphony Part One: 1970's to 2000". alloutguitar.com.

- ^ Fayazi, Mohsen (3 June 2014). "Wolf Hoffmann: 'I've always been a huge fan of Ritchie Blackmore'". Metal Shock Finland (World Assault ). Retrieved 28 June 2015.

- ^ "Smashing Pumpkins: 'There Are Always More Riffs Than Words'". Ultimate-guitar.com. Archived from the original on 27 October 2014. Retrieved 27 October 2014.

- ^ Wood, James (1 March 2016). "Lita Ford Talks New Memoir, 'Living Like a Runaway'". Guitar World.

- ^ "people dont talk about ritchie blackmore enough brian may praises uncompromising work in deep purple rainbow". somethingelsereviews. 20 January 2014.

- ^ "30 guitarists on the guitar heroes who changed their life". Classic Rock. 26 August 2023. Retrieved 7 May 2024.

- ^ Chopik, Ivan (24 February 2006). "Yngwie Malmsteen interview". guitarmessenger.com.

- ^ Grow, Kory (22 August 2012). "Dave Grohl Gets Lars Ulrich Talking About His First Album". Spin. Retrieved 18 October 2024.

- ^ Grow, Kory (9 April 2014). "Metallica's Lars Ulrich on the Rock Hall – 'Two Words: Deep Purple'". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 18 October 2014.

- ^ Lailana, Joe (September 1989). "The One & Only". Guitar School. Archived from the original on 23 February 2013. Retrieved 18 October 2024.

- ^ Li, John (12 March 2011). "Yngwie Malmsteen: Genius, Thief or Both?". Guitar World. Retrieved 3 August 2014.

- ^ Sharpe-Young, Garry (2009). "Yngwie Malmsteen – Biography". MusicMight. Archived from the original on 18 August 2014. Retrieved 18 October 2024.

Further reading

edit- Bloom, Jerry (2006). Black Knight – The Ritchie Blackmore Story. Omnibus Press.

- Davies, Roy (2002). Rainbow Rising. The Story of Ritchie Blackmore's Rainbow. Helter Skelter. ISBN 1900924315.

- Popoff, Martin (2005). Rainbow – English Castle Magic. Metal Blade.

- Tiven, Jon (March 1975). "Blackmore". International Musician and Recording World. 1. London: 4–7.

External links

edit- The Official Blackmore's Night website

- Ritchie Blackmore at AllMusic

- Ritchie Blackmore discography at Discogs