Malayo-Polynesian languages: Difference between revisions

No edit summary Tags: Reverted section blanking Mobile edit Mobile web edit |

m Reverted edits by 174.253.66.154 (talk) to last version by Tpdwkouaa |

||

| Line 36: | Line 36: | ||

Two morphological characteristics of the Malayo-Polynesian languages are a system of [[affix]]ation and [[reduplication]] (repetition of all or part of a word, such as ''[[wiki-wiki]])'' to form new words. Like other Austronesian languages, they have small phonemic inventories; thus a text has few but frequent sounds. The majority also lack [[Consonant cluster|consonant clusters]]. Most also have only a small set of vowels, five being a common number. |

Two morphological characteristics of the Malayo-Polynesian languages are a system of [[affix]]ation and [[reduplication]] (repetition of all or part of a word, such as ''[[wiki-wiki]])'' to form new words. Like other Austronesian languages, they have small phonemic inventories; thus a text has few but frequent sounds. The majority also lack [[Consonant cluster|consonant clusters]]. Most also have only a small set of vowels, five being a common number. |

||

==Major languages== |

|||

{{see also|List of major and official Austronesian languages}} |

|||

All major and official Austronesian languages belong to the Malayo-Polynesian subgroup. Malayo-Polynesian languages with more than five million speakers are: [[Malay language|Malay]] (including [[Indonesian language|Indonesian]]), [[Javanese language|Javanese]], [[Sundanese language|Sundanese]], [[Tagalog language|Tagalog]], [[Malagasy language|Malagasy]], [[Cebuano language|Cebuano]], [[Madurese language|Madurese]], [[Ilocano language|Ilocano]], [[Hiligaynon language|Hiligaynon]], and [[Minangkabau language|Minangkabau]]. |

|||

Among the remaining more than 1,000 languages, several have national/official language status, e.g. [[Tongan language|Tongan]], [[Samoan language|Samoan]], [[Māori language|Māori]], [[Gilbertese language|Gilbertese]], [[Fijian language|Fijian]], [[Hawaiian language|Hawaiian]], [[Palauan language|Palauan]], and [[Chamorro language|Chamorro]]. |

|||

== Typological characteristics == |

|||

{{main|Austronesian languages#Typological characteristics}} |

|||

==Terminology== |

|||

The term "Malayo-Polynesian" was originally coined in 1841 by [[Franz Bopp]] as the name for the Austronesian language family as a whole, and until the mid-20th century (after the introduction of the term "Austronesian" by [[Wilhelm Schmidt (linguist)|Wilhelm Schmidt]] in 1906), "Malayo-Polynesian" and "Austronesian" were used as synonyms. The current use of "Malayo-Polynesian" denoting the subgroup comprising all Austronesian languages outside of Taiwan was introduced in the 1970s, and has eventually become standard terminology in Austronesian studies.<ref name=Blust2013/> |

|||

==Classification== |

|||

===Relation to Austronesian languages on Taiwan=== |

|||

In spite of a few features shared with the [[Eastern Formosan languages]] (such as the merger of [[Proto-Austronesian language|proto-Austronesian]] *t, *C to /t/), there is no conclusive evidence that would link the Malayo-Polynesian languages to any one of the primary branches of Austronesian on Taiwan.<ref name=Blust2013>{{cite book |last=Blust |first=Robert |title=The Austronesian Languages |edition=revised|publisher=Australian National University|year=2013|isbn=978-1-922185-07-5|hdl=1885/10191 }}</ref> |

|||

===Internal classification=== |

|||

Malayo-Polynesian consists of a large number of small local language clusters, with the one exception being [[Oceanic languages|Oceanic]], the only large group which is universally accepted; its parent language [[Proto-Oceanic language|Proto-Oceanic]] has been reconstructed in all aspects of its structure (phonology, lexicon, morphology and syntax). All other large groups within Malayo-Polynesian are controversial. |

|||

The most influential proposal for the internal subgrouping of the Malayo-Polynesian languages was made by [[Robert Blust]] who presented several papers advocating a division into two major branches, viz. '''Western Malayo-Polynesian''' and '''Central-Eastern Malayo-Polynesian'''.<ref>Blust, R. (1993). |

|||

[https://www.jstor.org/stable/3623195 Central and Central-Eastern Malayo-Polynesian.] ''Oceanic Linguistics, 32''(2), 241–293.</ref> |

|||

[[Central-Eastern Malayo-Polynesian languages|Central-Eastern Malayo-Polynesian]] is widely accepted as a subgroup, although some objections have been raised against its validity as a genetic subgroup.<ref>[[Malcolm Ross (linguist)|Ross, Malcolm]] (2005), "Some current issues in Austronesian linguistics", in D.T. Tryon, ed., ''Comparative Austronesian Dictionary'', 1, 45–120. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.</ref><ref>Donohue, M., & Grimes, C. (2008). [https://www.jstor.org/stable/20172341 Yet More on the Position of the Languages of Eastern Indonesia and East Timor.] ''Oceanic Linguistics, 47''(1), 114–158.</ref> On the other hand, [[Western Malayo-Polynesian languages|Western Malayo-Polynesian]] is now generally held (including by Blust himself) to be an umbrella term without genetic relevance. Taking into account the [[Central-Eastern Malayo-Polynesian languages|Central-Eastern Malayo-Polynesian]] hypothesis, the Malayo-Polynesian languages can be divided into the following subgroups (proposals for larger subgroups are given below):<ref>Adelaar, K. Alexander, and Himmelmann, Nikolaus. 2005. ''The Austronesian languages of Asia and Madagascar.'' London: Routledge.</ref> |

|||

*[[Philippine languages|Philippine]] (disputed) |

|||

**[[Batanic languages]] |

|||

**[[Northern Luzon languages|Northern Luzon]] |

|||

**[[Central Luzon languages|Central Luzon]] |

|||

**[[Northern Mindoro languages|Northern Mindoro]] |

|||

**[[Greater Central Philippine languages|Greater Central Philippine]] |

|||

**[[Kalamian languages|Kalamian]] |

|||

**[[South Mindanao languages|South Mindanao]] (also called Bilic languages) |

|||

**[[Sangiric languages|Sangiric]] |

|||

**[[Minahasan languages|Minahasan]] |

|||

**[[Umiray Dumaget language|Umiray Dumaget]] |

|||

**[[Philippine languages|Manide-Inagta]] |

|||

**[[Ati language (Philippines)|Ati]] |

|||

*[[Sama–Bajaw languages|Sama–Bajaw]] |

|||

*[[Greater North Borneo languages|North Bornean]] |

|||

**[[Sabahan languages|Northeast Sabahan]] |

|||

**[[Sabahan languages|Southwest Sabahan]] |

|||

**[[North Sarawak languages|North Sarawak]] |

|||

*[[Kayan–Murik languages|Kayan–Murik]] |

|||

*[[Land Dayak languages|Land Dayak]] |

|||

*[[Barito languages|Barito]] (including [[Malagasy language|Malagasy]]) |

|||

*[[Moklenic languages|Moken–Moklen]] |

|||

*[[Malayo-Chamic languages|Malayo-Chamic]] |

|||

*[[Northwest Sumatra–Barrier Islands languages|Northwest Sumatra–Barrier Islands]] (probably including the [[Enggano language]]) |

|||

*[[Rejang language|Rejang]] |

|||

*[[Lampung language|Lampung]] |

|||

*[[Sundanese language|Sundanese]] |

|||

*[[Javanese language|Javanese]] |

|||

*[[Madurese language|Madurese]] |

|||

*[[Bali-Sasak-Sumbawa languages|Bali-Sasak-Sumbawa]] |

|||

*[[Celebic languages|Celebic]] |

|||

*[[South Sulawesi languages|South Sulawesi]] |

|||

*[[Palauan language|Palauan]] |

|||

*[[Chamorro language|Chamorro]] |

|||

*[[Central–Eastern Malayo-Polynesian languages|Central–Eastern Malayo-Polynesian]] |

|||

**[[Central Malayo-Polynesian languages|Central Malayo-Polynesian]] (dubious) |

|||

***[[Sumba–Flores languages|Sumba–Flores]] |

|||

***[[Flores–Lembata languages|Flores–Lembata]] |

|||

***[[Selaru languages|Selaru]] |

|||

***[[Kei–Tanimbar languages|Kei–Tanimbar]] |

|||

***[[Aru languages|Aru]] |

|||

***[[Central Maluku languages|Central Maluku]] |

|||

***[[Timoric languages|Timoric]] (also called Timor–Babar languages) |

|||

***[[Kowiai language|Kowiai]] |

|||

***[[Teor-Kur language|Teor-Kur]] |

|||

**Eastern Malayo-Polynesian (dubious) |

|||

***[[South Halmahera–West New Guinea languages|South Halmahera–West New Guinea]] |

|||

***[[Oceanic languages|Oceanic]] (approximately 450 languages) |

|||

====Nasal==== |

|||

The position of the recently rediscovered [[Nasal language]] (spoken on Sumatra) is unclear; it shares features of lexicon and phonology with both [[Lampung languages|Lampung]] and [[Rejangese language|Rejang]].<ref>Anderbeck, Karl; Aprilani, Herdian (2013). ''[http://www.sil.org/resources/publications/entry/54043 The Improbable Language: Survey Report on the Nasal Language of Bengkulu, Sumatra]''. SIL Electronic Survey Report. SIL International.</ref> |

|||

====Enggano==== |

|||

Edwards (2015)<ref name="Edwards2015">Edwards, Owen (2015). "The Position of Enggano within Austronesian." ''Oceanic Linguistics'' 54 (1): 54-109.</ref> argues that [[Enggano language|Enggano]] is a primary branch of Malayo-Polynesian. However, this is disputed by Smith (2017), who considers Enggano to have undergone significant internal changes, but to have once been much more like other Sumatran languages in Sumatra. |

|||

====Philippine languages==== |

|||

{{main|Philippine languages}} |

|||

The status of the Philippine languages as subgroup of Malayo-Polynesian is disputed. While many scholars (such as [[Robert Blust]]) support a genealogical subgroup that includes the languages of the Philippines and northern Sulawesi,<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Blust |first=Robert |year=2019 |title=The Resurrection of Proto-Philippines |journal=Oceanic Linguistics |volume=58 |issue=2 |pages=153–256 |doi=10.1353/ol.2019.0008 |ref=apa}}</ref> Reid (2018) rejects the hypothesis of a single Philippine subgroup, but instead argues that the Philippine branches represent first-order subgroups directly descended from Proto-Malayo-Polynesian.<ref name="Reid2018">Reid, Lawrence A. 2018. "[https://minpaku.repo.nii.ac.jp/?action=repository_uri&item_id=7893&file_id=22&file_no=1 Modeling the linguistic situation in the Philippines]." In ''Let's Talk about Trees'', ed. by Ritsuko Kikusawa and Lawrence A. Reid. Osaka: Senri Ethnological Studies, Minpaku. {{doi|10.15021/00009006}}</ref> |

|||

===={{vanchor|Nuclear Malayo-Polynesian}} (Zobel 2002)==== <!--target of redirect [[Nuclear Malayo-Polynesian languages]]--> |

|||

Zobel (2002) proposes a ''Nuclear Malayo-Polynesian'' subgroup, based on putative shared innovations in the [[Austronesian alignment]] and [[syntax]] found throughout Indonesia apart from much of Borneo and the north of Sulawesi. This subgroup comprises the languages of the [[Greater Sunda Islands]] ([[Malayo-Chamic languages|Malayo-Chamic]], [[Northwest Sumatra–Barrier Islands languages|Northwest Sumatra–Barrier Islands]], [[Lampung language|Lampung]], [[Sundanese language|Sundanese]], [[Javanese language|Javanese]], [[Madurese language|Madurese]], [[Bali-Sasak-Sumbawa languages|Bali-Sasak-Sumbawa]]) and most of Sulawesi ([[Celebic languages|Celebic]], [[South Sulawesi languages|South Sulawesi]]), [[Palauan language|Palauan]], [[Chamorro language|Chamorro]] and the [[Central–Eastern Malayo-Polynesian languages]].<ref>Zobel, Erik, "The position of Chamorro and Palauan in the Austronesian family tree: evidence from verb morphosyntax". In: Fay Wouk and Malcolm Ross (ed.), 2002. ''The history and typology of western Austronesian voice systems.'' Australian National University.</ref> This hypothesis is one of the few attempts to link certain [[Western Malayo-Polynesian languages]] with the [[Central-Eastern Malayo-Polynesian languages]] in a higher intermediate subgroup, but has received little further scholarly attention. |

|||

====Malayo-Sumbawan (Adelaar 2005)==== |

|||

{{main|Malayo-Sumbawan languages}} |

|||

The Malayo-Sumbawan languages are a proposal by [[K. Alexander Adelaar]] (2005) which unites the [[Malayo-Sumbawan languages|Malayo-Chamic languages]], the [[Bali-Sasak-Sumbawa languages]], [[Madurese language|Madurese]] and [[Sundanese language|Sundanese]] into a single subgroup based on phonological and lexical evidence.<ref>Adelaar, A. (2005). [https://www.jstor.org/stable/3623345 Malayo-Sumbawan.] ''Oceanic Linguistics, 44''(2), 357–388.</ref> |

|||

*Malayo-Sumbawan |

|||

**Malayo-Chamic-BSS |

|||

***[[Malayic languages|Malayic]] |

|||

***[[Chamic languages|Chamic]] |

|||

***[[Bali-Sasak-Sumbawa languages|Bali-Sasak-Sumbawa]] |

|||

**[[Sundanese language|Sundanese]] |

|||

**[[Madurese language|Madurese]] |

|||

====Greater North Borneo (Blust 2010; Smith 2017, 2017a)==== |

|||

{{main|Greater North Borneo languages}} |

|||

The Greater North Borneo hypothesis, which unites all languages spoken on Borneo except for the [[Barito languages]] together with the [[Malayo-Sumbawan languages|Malayo-Chamic languages]], [[Rejangese language|Rejang]] and [[Sundanese language|Sundanese]] into a single subgroup, was first proposed by Blust (2010) and further elaborated by Smith (2017, 2017a).<ref name=Blust2010>{{cite journal| last=Blust |first=Robert |title=The Greater North Borneo Hypothesis |year=2010 |journal=Oceanic Linguistics |volume=49 |issue=1 |pages=44–118 |jstor=40783586 |doi=10.1353/ol.0.0060 }}</ref><ref name=SmithWMP>{{cite journal| last=Smith |first=Alexander D. |title=The Western Malayo-Polynesian Problem |year=2017 |journal=Oceanic Linguistics |volume=56 |issue=2 |page=435–490|doi=10.1353/ol.2017.0021 }} </ref><ref>Smith, Alexander (2017a). ''The Languages of Borneo: A Comprehensive Classification''. PhD Dissertation: University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa.</ref> |

|||

*[[Greater North Borneo languages|Greater North Borneo]] |

|||

**[[Bornean languages|North Borneo]] |

|||

***[[Sabahan languages|Northeast Sabah]] |

|||

***[[Sabahan languages|Southwest Sabah]] |

|||

***[[North Sarawak languages|North Sarawak]] |

|||

**[[Kayan–Murik languages|Kayan–Murik]] |

|||

**[[Land Dayak languages|Land Dayak]] |

|||

**[[Malayo-Chamic languages|Malayo-Chamic]] |

|||

**[[Moklenic languages|Moken]] (not included by Smith (2017)) |

|||

**[[Rejang language|Rejang]] |

|||

**[[Sundanese language|Sundanese]] |

|||

Because of the inclusion of Malayo-Chamic and Sundanese, the Greater North Borneo hypothesis is incompatible with Adelaar's Malayo-Sumbawan proposal. Consequently, Blust explicitly rejects Malayo-Sumbawan as a subgroup. The Greater North Borneo subgroup is based solely on lexical evidence. |

|||

====Smith (2017)==== <!--target of redirect [[Western Indonesian languages]]--> |

|||

Based on a proposal initially brought forward by Blust (2010) as an extension of the Greater North Borneo hypothesis,<ref name=Blust2010/> Smith (2017) unites several Malayo-Polynesian subgroups in a "Western Indonesian" group, thus greatly reducing the number of primary branches of Malayo-Polynesian:<ref name=SmithWMP/> |

|||

*Western Indonesian |

|||

**[[Greater North Borneo languages|Greater North Borneo]] |

|||

***North Borneo |

|||

****[[Sabahan languages|Northeast Sabah]] |

|||

****[[Sabahan languages|Southwest Sabah]] |

|||

****[[North Sarawakan languages|North Sarawak]] |

|||

***[[Melanau–Kajang languages|Central Sarawak]] |

|||

***[[Kayan–Murik languages|Kayanic]] |

|||

***[[Land Dayak languages|Land Dayak]] |

|||

***[[Malayic languages|Malayic]] |

|||

***[[Chamic languages|Chamic]] |

|||

***[[Sundanese language|Sundanese]] |

|||

***[[Rejang language|Rejang]] |

|||

**Greater Barito ([[linkage (linguistics)|linkage]]) |

|||

***[[Sama–Bajaw languages|Sama–Bajaw]] |

|||

***[[Barito languages|Greater Barito]] ([[paraphyletic]] [[linkage (linguistics)|linkage]]<ref>Smith, Alexander D. 2018. [http://hdl.handle.net/10524/52418 The Barito Linkage Hypothesis, with a Note on the Position of Basap]. JSEALS Volume 11.1 (2018).</ref>) |

|||

**[[Lampung language|Lampung]] |

|||

**[[Javanese language|Javanese]] |

|||

**[[Madurese language|Madurese]] |

|||

**[[Bali-Sasak-Sumbawa languages|Bali-Sasak-Sumbawa]] |

|||

*Sumatran<br/>(an extended version of [[Northwest Sumatra–Barrier Islands languages|Northwest Sumatra–Barrier Islands]] that also comprises [[Nasal language|Nasal]]; the question of internal subgrouping is left open by Smith) |

|||

*[[Celebic languages|Celebic]] |

|||

*[[South Sulawesi languages|South Sulawesi]] |

|||

*[[Palauan language|Palauan]] |

|||

*[[Chamorro language|Chamorro]] |

|||

*[[Moklenic languages|Moklenic]] |

|||

*[[Central–Eastern Malayo-Polynesian languages|Central–Eastern Malayo-Polynesian]] |

|||

*[[Philippine languages|Philippine]] ([[linkage (linguistics)|linkage]])<br/>(according to Smith, "not a subgroup as much as a [[linkage (linguistics)|loosely related group]] of languages that may contain multiple primary branches") |

|||

==See also== |

|||

*[[Austronesian peoples]] |

|||

==References== |

|||

{{reflist}} |

|||

==External links== |

==External links== |

||

Revision as of 21:46, 1 October 2021

| Malayo-Polynesian | |

|---|---|

| Geographic distribution | Southeast Asia, East Asia, the Pacific, Madagascar |

| Linguistic classification | Austronesian

|

| Proto-language | Proto-Malayo-Polynesian |

| Subdivisions |

|

| ISO 639-5 | poz |

| Glottolog | mala1545 |

The western sphere of Malayo-Polynesian languages. (The bottom three are Central-Eastern Malayo-Polynesian)

other Western Malayo-Polynesian languages (geographic)

Central Malayo-Polynesian (geographic)

the westernmost Oceanic languages | |

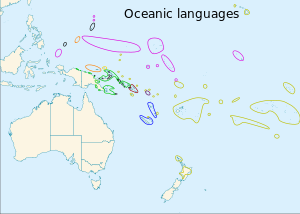

The branches of the Oceanic languages:

Black ovals at the northwestern limit of Micronesia are the non-Oceanic languages Palauan and Chamorro. Black circles within green are offshore Papuan languages. | |

The Malayo-Polynesian languages are a subgroup of the Austronesian languages, with approximately 385.5 million speakers. The Malayo-Polynesian languages are spoken by the Austronesian peoples outside of Taiwan, in the island nations of Southeast Asia and the Pacific Ocean, with a smaller number in continental Asia in the areas near the Malay Peninsula. Cambodia, Vietnam and the Chinese island Hainan serve as the northwest geographic outlier. Malagasy, spoken in the island of Madagascar off the eastern coast of Africa in the Indian Ocean, is the furthest western outlier. The languages spoken south-westward from central Micronesia until Easter Island are sometimes referred to as the Polynesian languages.

Many languages of the Malayo-Polynesian family show the strong influence of Sanskrit and Arabic, as the western part of the region has been a stronghold of Hinduism, Buddhism, and, later, Islam.

Two morphological characteristics of the Malayo-Polynesian languages are a system of affixation and reduplication (repetition of all or part of a word, such as wiki-wiki) to form new words. Like other Austronesian languages, they have small phonemic inventories; thus a text has few but frequent sounds. The majority also lack consonant clusters. Most also have only a small set of vowels, five being a common number.

Major languages

All major and official Austronesian languages belong to the Malayo-Polynesian subgroup. Malayo-Polynesian languages with more than five million speakers are: Malay (including Indonesian), Javanese, Sundanese, Tagalog, Malagasy, Cebuano, Madurese, Ilocano, Hiligaynon, and Minangkabau. Among the remaining more than 1,000 languages, several have national/official language status, e.g. Tongan, Samoan, Māori, Gilbertese, Fijian, Hawaiian, Palauan, and Chamorro.

Typological characteristics

Terminology

The term "Malayo-Polynesian" was originally coined in 1841 by Franz Bopp as the name for the Austronesian language family as a whole, and until the mid-20th century (after the introduction of the term "Austronesian" by Wilhelm Schmidt in 1906), "Malayo-Polynesian" and "Austronesian" were used as synonyms. The current use of "Malayo-Polynesian" denoting the subgroup comprising all Austronesian languages outside of Taiwan was introduced in the 1970s, and has eventually become standard terminology in Austronesian studies.[1]

Classification

Relation to Austronesian languages on Taiwan

In spite of a few features shared with the Eastern Formosan languages (such as the merger of proto-Austronesian *t, *C to /t/), there is no conclusive evidence that would link the Malayo-Polynesian languages to any one of the primary branches of Austronesian on Taiwan.[1]

Internal classification

Malayo-Polynesian consists of a large number of small local language clusters, with the one exception being Oceanic, the only large group which is universally accepted; its parent language Proto-Oceanic has been reconstructed in all aspects of its structure (phonology, lexicon, morphology and syntax). All other large groups within Malayo-Polynesian are controversial.

The most influential proposal for the internal subgrouping of the Malayo-Polynesian languages was made by Robert Blust who presented several papers advocating a division into two major branches, viz. Western Malayo-Polynesian and Central-Eastern Malayo-Polynesian.[2]

Central-Eastern Malayo-Polynesian is widely accepted as a subgroup, although some objections have been raised against its validity as a genetic subgroup.[3][4] On the other hand, Western Malayo-Polynesian is now generally held (including by Blust himself) to be an umbrella term without genetic relevance. Taking into account the Central-Eastern Malayo-Polynesian hypothesis, the Malayo-Polynesian languages can be divided into the following subgroups (proposals for larger subgroups are given below):[5]

- Philippine (disputed)

- Batanic languages

- Northern Luzon

- Central Luzon

- Northern Mindoro

- Greater Central Philippine

- Kalamian

- South Mindanao (also called Bilic languages)

- Sangiric

- Minahasan

- Umiray Dumaget

- Manide-Inagta

- Ati

- Sama–Bajaw

- North Bornean

- Kayan–Murik

- Land Dayak

- Barito (including Malagasy)

- Moken–Moklen

- Malayo-Chamic

- Northwest Sumatra–Barrier Islands (probably including the Enggano language)

- Rejang

- Lampung

- Sundanese

- Javanese

- Madurese

- Bali-Sasak-Sumbawa

- Celebic

- South Sulawesi

- Palauan

- Chamorro

- Central–Eastern Malayo-Polynesian

- Central Malayo-Polynesian (dubious)

- Sumba–Flores

- Flores–Lembata

- Selaru

- Kei–Tanimbar

- Aru

- Central Maluku

- Timoric (also called Timor–Babar languages)

- Kowiai

- Teor-Kur

- Eastern Malayo-Polynesian (dubious)

- South Halmahera–West New Guinea

- Oceanic (approximately 450 languages)

- Central Malayo-Polynesian (dubious)

Nasal

The position of the recently rediscovered Nasal language (spoken on Sumatra) is unclear; it shares features of lexicon and phonology with both Lampung and Rejang.[6]

Enggano

Edwards (2015)[7] argues that Enggano is a primary branch of Malayo-Polynesian. However, this is disputed by Smith (2017), who considers Enggano to have undergone significant internal changes, but to have once been much more like other Sumatran languages in Sumatra.

Philippine languages

The status of the Philippine languages as subgroup of Malayo-Polynesian is disputed. While many scholars (such as Robert Blust) support a genealogical subgroup that includes the languages of the Philippines and northern Sulawesi,[8] Reid (2018) rejects the hypothesis of a single Philippine subgroup, but instead argues that the Philippine branches represent first-order subgroups directly descended from Proto-Malayo-Polynesian.[9]

Nuclear Malayo-Polynesian (Zobel 2002)

Zobel (2002) proposes a Nuclear Malayo-Polynesian subgroup, based on putative shared innovations in the Austronesian alignment and syntax found throughout Indonesia apart from much of Borneo and the north of Sulawesi. This subgroup comprises the languages of the Greater Sunda Islands (Malayo-Chamic, Northwest Sumatra–Barrier Islands, Lampung, Sundanese, Javanese, Madurese, Bali-Sasak-Sumbawa) and most of Sulawesi (Celebic, South Sulawesi), Palauan, Chamorro and the Central–Eastern Malayo-Polynesian languages.[10] This hypothesis is one of the few attempts to link certain Western Malayo-Polynesian languages with the Central-Eastern Malayo-Polynesian languages in a higher intermediate subgroup, but has received little further scholarly attention.

Malayo-Sumbawan (Adelaar 2005)

The Malayo-Sumbawan languages are a proposal by K. Alexander Adelaar (2005) which unites the Malayo-Chamic languages, the Bali-Sasak-Sumbawa languages, Madurese and Sundanese into a single subgroup based on phonological and lexical evidence.[11]

Greater North Borneo (Blust 2010; Smith 2017, 2017a)

The Greater North Borneo hypothesis, which unites all languages spoken on Borneo except for the Barito languages together with the Malayo-Chamic languages, Rejang and Sundanese into a single subgroup, was first proposed by Blust (2010) and further elaborated by Smith (2017, 2017a).[12][13][14]

- Greater North Borneo

- North Borneo

- Kayan–Murik

- Land Dayak

- Malayo-Chamic

- Moken (not included by Smith (2017))

- Rejang

- Sundanese

Because of the inclusion of Malayo-Chamic and Sundanese, the Greater North Borneo hypothesis is incompatible with Adelaar's Malayo-Sumbawan proposal. Consequently, Blust explicitly rejects Malayo-Sumbawan as a subgroup. The Greater North Borneo subgroup is based solely on lexical evidence.

Smith (2017)

Based on a proposal initially brought forward by Blust (2010) as an extension of the Greater North Borneo hypothesis,[12] Smith (2017) unites several Malayo-Polynesian subgroups in a "Western Indonesian" group, thus greatly reducing the number of primary branches of Malayo-Polynesian:[13]

- Western Indonesian

- Sumatran

(an extended version of Northwest Sumatra–Barrier Islands that also comprises Nasal; the question of internal subgrouping is left open by Smith) - Celebic

- South Sulawesi

- Palauan

- Chamorro

- Moklenic

- Central–Eastern Malayo-Polynesian

- Philippine (linkage)

(according to Smith, "not a subgroup as much as a loosely related group of languages that may contain multiple primary branches")

See also

References

- ^ a b Blust, Robert (2013). The Austronesian Languages (revised ed.). Australian National University. hdl:1885/10191. ISBN 978-1-922185-07-5.

- ^ Blust, R. (1993). Central and Central-Eastern Malayo-Polynesian. Oceanic Linguistics, 32(2), 241–293.

- ^ Ross, Malcolm (2005), "Some current issues in Austronesian linguistics", in D.T. Tryon, ed., Comparative Austronesian Dictionary, 1, 45–120. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

- ^ Donohue, M., & Grimes, C. (2008). Yet More on the Position of the Languages of Eastern Indonesia and East Timor. Oceanic Linguistics, 47(1), 114–158.

- ^ Adelaar, K. Alexander, and Himmelmann, Nikolaus. 2005. The Austronesian languages of Asia and Madagascar. London: Routledge.

- ^ Anderbeck, Karl; Aprilani, Herdian (2013). The Improbable Language: Survey Report on the Nasal Language of Bengkulu, Sumatra. SIL Electronic Survey Report. SIL International.

- ^ Edwards, Owen (2015). "The Position of Enggano within Austronesian." Oceanic Linguistics 54 (1): 54-109.

- ^ Blust, Robert (2019). "The Resurrection of Proto-Philippines". Oceanic Linguistics. 58 (2): 153–256. doi:10.1353/ol.2019.0008.

- ^ Reid, Lawrence A. 2018. "Modeling the linguistic situation in the Philippines." In Let's Talk about Trees, ed. by Ritsuko Kikusawa and Lawrence A. Reid. Osaka: Senri Ethnological Studies, Minpaku. doi:10.15021/00009006

- ^ Zobel, Erik, "The position of Chamorro and Palauan in the Austronesian family tree: evidence from verb morphosyntax". In: Fay Wouk and Malcolm Ross (ed.), 2002. The history and typology of western Austronesian voice systems. Australian National University.

- ^ Adelaar, A. (2005). Malayo-Sumbawan. Oceanic Linguistics, 44(2), 357–388.

- ^ a b Blust, Robert (2010). "The Greater North Borneo Hypothesis". Oceanic Linguistics. 49 (1): 44–118. doi:10.1353/ol.0.0060. JSTOR 40783586.

- ^ a b Smith, Alexander D. (2017). "The Western Malayo-Polynesian Problem". Oceanic Linguistics. 56 (2): 435–490. doi:10.1353/ol.2017.0021.

- ^ Smith, Alexander (2017a). The Languages of Borneo: A Comprehensive Classification. PhD Dissertation: University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa.

- ^ Smith, Alexander D. 2018. The Barito Linkage Hypothesis, with a Note on the Position of Basap. JSEALS Volume 11.1 (2018).