Pluralistic ignorance: Difference between revisions

Alter: journal. Removed proxy/dead URL that duplicated identifier. | Use this tool. Report bugs. | #UCB_Gadget |

Added free to read link in citations with OAbot #oabot |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Short description|Incorrect perception of others' beliefs}} |

{{Short description|Incorrect perception of others' beliefs}} |

||

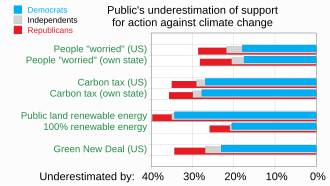

[[File:20220823 Public underestimation of public support for climate action - poll - false social reality.svg|thumb| upright=1.5 | Research found that 80–90% of Americans underestimate the prevalence of support for major climate change mitigation policies and climate concern among fellow Americans. While 66–80% Americans support these policies, Americans estimate the prevalence to be 37–43%—barely half as much. Researchers have called this misperception a ''false social reality,'' a form of pluralistic ignorance.<ref name=NatureComms_20220823>{{cite journal |last1=Sparkman |first1=Gregg |last2=Geiger |first2=Nathan |last3=Weber |first3=Elke U. |title=Americans experience a false social reality by underestimating popular climate policy support by nearly half |journal=Nature Communications |date=23 August 2022 |volume=13 |issue=1 |page=4779 |doi=10.1038/s41467-022-32412-y |pmid=35999211 |pmc=9399177 |bibcode=2022NatCo..13.4779S |doi-access=free }}</ref><ref> {{cite web |last1=Yoder |first1=Kate |title=Americans are convinced climate action is unpopular. They're very, very wrong. / Support for climate policies is double what most people think, a new study found. |url=https://grist.org/politics/americans-think-climate-action-unpopular-wrong-study/ |website=Grist |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220829104543/https://grist.org/politics/americans-think-climate-action-unpopular-wrong-study/ |archive-date=29 August 2022 |date=29 August 2022 |url-status=live}}</ref>]] |

[[File:20220823 Public underestimation of public support for climate action - poll - false social reality.svg|thumb| upright=1.5 | Research found that 80–90% of Americans underestimate the prevalence of support for major climate change mitigation policies and climate concern among fellow Americans. While 66–80% Americans support these policies, Americans estimate the prevalence to be 37–43%—barely half as much. Researchers have called this misperception a ''false social reality,'' a form of pluralistic ignorance.<ref name=NatureComms_20220823>{{cite journal |last1=Sparkman |first1=Gregg |last2=Geiger |first2=Nathan |last3=Weber |first3=Elke U. |title=Americans experience a false social reality by underestimating popular climate policy support by nearly half |journal=Nature Communications |date=23 August 2022 |volume=13 |issue=1 |page=4779 |doi=10.1038/s41467-022-32412-y |pmid=35999211 |pmc=9399177 |bibcode=2022NatCo..13.4779S |doi-access=free }}</ref><ref> {{cite web |last1=Yoder |first1=Kate |title=Americans are convinced climate action is unpopular. They're very, very wrong. / Support for climate policies is double what most people think, a new study found. |url=https://grist.org/politics/americans-think-climate-action-unpopular-wrong-study/ |website=Grist |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220829104543/https://grist.org/politics/americans-think-climate-action-unpopular-wrong-study/ |archive-date=29 August 2022 |date=29 August 2022 |url-status=live}}</ref>]] |

||

In [[social psychology]], '''pluralistic ignorance''' (also known as a collective illusion)<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Bicchieri |first1=Cristina |last2=Fukui |first2=Yoshitaka |title=The Great Illusion: Ignorance, Informational Cascades, and the Persistence of Unpopular Norms |url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/3857639 |journal=Business Ethics Quarterly |pages=127–155 |doi=10.2307/3857639 |date=1999|volume=9 |issue=1 |jstor=3857639 }}</ref> is a phenomenon in which people mistakenly believe that others predominantly hold an opinion different from their own.<ref>{{cite news |last1=Nickerson |first1=Charlotte |title=Pluralistic Ignorance: Definition & Examples |url=https://www.simplypsychology.org/pluralistic-ignorance.html |work=www.simplypsychology.org |date=May 11, 2022}}</ref> In this phenomenon, most people in a group may go along with a view they do not hold because they think, incorrectly, that most other people in the group hold it. Pluralistic ignorance encompasses situations in which a minority position on a given topic is wrongly perceived to be the majority position, or the majority position is wrongly perceived to be a minority position.<ref>{{Cite journal|last1=Miller|first1=Dale T.|last2=McFarland|first2=Cathy|date=1987|title=Pluralistic ignorance: When similarity is interpreted as dissimilarity.|url=http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.53.2.298|journal=Journal of Personality and Social Psychology|volume=53|issue=2|pages=298–305|doi=10.1037/0022-3514.53.2.298|issn=0022-3514}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|last1=Katz |first1=Daniel |first2=Floyd Henry |last2=Allport |first3=Margaret Babcock |last3=Jenness |title=Students' attitudes; a report of the Syracuse University reaction study |year=1931 |location=Syracuse, N.Y. |publisher=Craftsman Press}}</ref> |

In [[social psychology]], '''pluralistic ignorance''' (also known as a collective illusion)<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Bicchieri |first1=Cristina |last2=Fukui |first2=Yoshitaka |title=The Great Illusion: Ignorance, Informational Cascades, and the Persistence of Unpopular Norms |url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/3857639 |journal=Business Ethics Quarterly |pages=127–155 |doi=10.2307/3857639 |date=1999|volume=9 |issue=1 |jstor=3857639 |url-access=subscription }}</ref> is a phenomenon in which people mistakenly believe that others predominantly hold an opinion different from their own.<ref>{{cite news |last1=Nickerson |first1=Charlotte |title=Pluralistic Ignorance: Definition & Examples |url=https://www.simplypsychology.org/pluralistic-ignorance.html |work=www.simplypsychology.org |date=May 11, 2022}}</ref> In this phenomenon, most people in a group may go along with a view they do not hold because they think, incorrectly, that most other people in the group hold it. Pluralistic ignorance encompasses situations in which a minority position on a given topic is wrongly perceived to be the majority position, or the majority position is wrongly perceived to be a minority position.<ref>{{Cite journal|last1=Miller|first1=Dale T.|last2=McFarland|first2=Cathy|date=1987|title=Pluralistic ignorance: When similarity is interpreted as dissimilarity.|url=http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.53.2.298|journal=Journal of Personality and Social Psychology|volume=53|issue=2|pages=298–305|doi=10.1037/0022-3514.53.2.298|issn=0022-3514}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|last1=Katz |first1=Daniel |first2=Floyd Henry |last2=Allport |first3=Margaret Babcock |last3=Jenness |title=Students' attitudes; a report of the Syracuse University reaction study |year=1931 |location=Syracuse, N.Y. |publisher=Craftsman Press}}</ref> |

||

Pluralistic ignorance can arise in different ways. An individual may misjudge overall perceptions of a topic due to fear, embarrassment, social desirability, or social inhibition. Individuals may develop collective illusions when they feel they will receive backlash when they think their belief differs from society's belief.<ref name="Anne">{{cite news |last1=Schwenkenbecher |first1=Anne |title=How We Fail to Know: Group-Based Ignorance and Collective Epistemic Obligations |url=https://philpapers.org/archive/SCHHWF.pdf |date=16 February 2021}}</ref> However, pluralistic ignorance describes the coincidence of a belief with inaccurate perceptions, but not the process by which those inaccurate perceptions are arrived at. |

Pluralistic ignorance can arise in different ways. An individual may misjudge overall perceptions of a topic due to fear, embarrassment, social desirability, or social inhibition. Individuals may develop collective illusions when they feel they will receive backlash when they think their belief differs from society's belief.<ref name="Anne">{{cite news |last1=Schwenkenbecher |first1=Anne |title=How We Fail to Know: Group-Based Ignorance and Collective Epistemic Obligations |url=https://philpapers.org/archive/SCHHWF.pdf |date=16 February 2021}}</ref> However, pluralistic ignorance describes the coincidence of a belief with inaccurate perceptions, but not the process by which those inaccurate perceptions are arrived at. |

||

Revision as of 10:32, 14 December 2023

In social psychology, pluralistic ignorance (also known as a collective illusion)[3] is a phenomenon in which people mistakenly believe that others predominantly hold an opinion different from their own.[4] In this phenomenon, most people in a group may go along with a view they do not hold because they think, incorrectly, that most other people in the group hold it. Pluralistic ignorance encompasses situations in which a minority position on a given topic is wrongly perceived to be the majority position, or the majority position is wrongly perceived to be a minority position.[5][6]

Pluralistic ignorance can arise in different ways. An individual may misjudge overall perceptions of a topic due to fear, embarrassment, social desirability, or social inhibition. Individuals may develop collective illusions when they feel they will receive backlash when they think their belief differs from society's belief.[7] However, pluralistic ignorance describes the coincidence of a belief with inaccurate perceptions, but not the process by which those inaccurate perceptions are arrived at.

A common example of pluralistic ignorance is the bystander effect,[8] where individual onlookers may believe others are considering taking action, and may therefore themselves refrain from acting. This results in all the individual onlookers believing that the majority of onlookers are taking action, when in reality few or none of the onlookers take action.[7]

Research

Prentice and Miller conducted a contemporary study on pluralistic ignorance, examining individuals beliefs on alcohol use and estimating the attitudes of their peers.[9] The authors found that, on average, individual levels of comfort with drinking practices on campus were much lower than the perceived average. In one subset of experiments they traced the attitude change toward alcohol consumption of men versus women over the semester. In men, the authors found a shifting of private attitudes toward this perceived norm, demonstrating a form of cognitive dissonance. Women were found to have no shift in attitude over the course of the semester. Additionally, students perceived deviance from the social norm on alcohol use was correlated with various measures of campus alienation. Even though that deviance from the social norm was only perceived, it shows how isolation from the larger population can lead to larger differences between an individual's belief and the populations belief, leading to pluralistic ignorance. This study showed that the university students showcased pluralistic ignorance by individuals believing that the general populations comfort level with drinking practices was significantly higher than their personal comfort level, when in reality the individuals comfort level was quite similar to the general populations comfort level.

Additional research has shown that pluralistic ignorance plagues not only those who indulge, but also those who abstain. Examples consist of individuals beliefs on traditional vices such as gambling, smoking and drinking to lifestyles such as vegetarianism.[10] With the latter showcasing that pluralistic ignorance can be caused by the structure of the underlying social network, not exclusively cognitive dissonance, demonstrating how pluralistic ignorance can arise through a variety of methods.

The theory of pluralistic ignorance was studied by Floyd Henry Allport and his students Daniel Katz and Richard Schanck.[11] He produced studies of racial stereotyping and prejudice, and attitude change, and his pursuit of the connections between individual psychology and social systems helped to found the field of organizational psychology.[12] Elisabeth Noelle-Neumann, in her spiral of silence theory, argued that media biases lead to pluralistic ignorance.[13]

Further behavioral economic and social psychology research was done by Todd Rose to demonstrate the interchangeability of the terms pluralistic ignorance and collective illusions. His findings of historical events, scientific studies and social media patterns indicate that by using either term you are saying the same thing. The societal systems like ours unconsciously participate in perpetuating false beliefs and narratives with a desire to fit in.[14]

Examples

Pluralistic ignorance was blamed for exacerbating support for racial segregation in the United States. It has also been named a reason for the illusory popular support that kept the Communist Party of the Soviet Union in power, as many opposed the regime but assumed that others were supporters of it. Thus, most people were afraid to voice their opposition.[15]

Another case of pluralistic ignorance concerns drinking on campus in countries where alcohol use is prevalent at colleges and universities. Students drink at weekend parties and sometimes at evening study breaks. Many drink to excess, some on a routine basis. The high visibility of heavy drinking on campus, combined with reluctance by students to show any public signs of concern or disapproval, gives rise to pluralistic ignorance: Students believe that their peers are much more comfortable with this behavior than they themselves feel.[16]

Hans Christian Andersen's fairy tale "The Emperor's New Clothes"[17] is a famous fictional case of pluralistic ignorance. In this story two con artists come into the Emperor's kingdom and convince him that they make the finest clothes in all of the land that can only be seen by anyone who was not stupid. The con artists continued to steal gold, silk and other precious items for their "unique creation". Out of fear for being seen as stupid, all of the emperor's men and townspeople kept silent about the fact they could not see the emperor's clothes until finally a small child comes forth and says that the emperor isn't wearing any clothes. Once the child is willing to admit that he cannot see any clothes on the emperor, the emperor and townspeople finally admit that the emperor has been tricked and that there was never an outfit being made.

Pluralistic ignorance has also been blamed for large majorities of the public remaining silent on climate change—while 'solid majorities' of the American and UK public are concerned about climate change, most erroneously believe they are in the minority with their concern.[18] It has been suggested that pollution-intensive industries have contributed to the public's underestimation of public support for climate solutions.[19] For example, in the U.S., support for pollution pricing is high,[20][21] yet public perception of public support is much lower.[19]

Another example of pluralistic ignorance is the tulip mania of 1634. It is a great example of how investors can be swept up in a financial frenzy due to collective illusion. The Dutch elite decided that having one’s own unique collection of the spring flowering bulbs was an absolute necessity. So, despite the flower’s lack of any intrinsic value, the prices began to rise.[22]

In August 2022, Nature Communications published a survey with 6,119 representatively sampled Americans that found that 66 to 80% of Americans supported major climate change mitigation policies (i.e. 100% renewable energy by 2035, Green New Deal, carbon tax and dividend, renewable energy production siting on public land) and expressed climate concern, but that 80 to 90% of Americans underestimated the prevalence of support for such policies and such concern by their fellow Americans (with the sample estimating that only 37 to 43% on average supported such policies). Americans in every state and every assessed demographic (e.g. political ideology, racial group, urban/suburban/rural residence, educational attainment) underestimated support across all policies tested, and every state survey group and every demographic assessed underestimated support for the climate policies by at least 20%. The researchers attributed the misperception among the general public to pluralistic ignorance. Conservatives were found to underestimate support for the policies due to a false consensus effect, exposure to more conservative local norms, and consumption of conservative news, while liberals were suggested to underestimate support for the policies due to a false-uniqueness effect.[1][23]

Men's conceptions of how they are expected to conform to norms of masculinity present additional examples of pluralistic ignorance. Specifically, most college age men are uncomfortable with other men "bragging about sexual acts and giving details," but erroneously believe themselves to be in the minority for their discomfort. Similarly, college age men underestimate other men's "desire to make sure they have consent when sexually active". This "role-conflict" can have deleterious consequences for men's physical and mental health, as well as for society.[16] Netflix's "Derren Brown: The Push" explores some aspects of these concepts. [24]

According to a 2020 study, the vast majority of young married men in Saudi Arabia express private beliefs in support of women working outside the home but they substantially underestimate the degree to which other similar men support it. Once they become informed about the widespread nature of the support, they increasingly help their wives obtain jobs.[25]

According to a 2023 survey, most Americans do not prioritize college while believing most other Americans do. Similarly, the belief that society doesn’t prioritize personally fulfilling work or that others desire a one-size-fits-all model of education is a collective illusion.[26]

Consequences

Pluralistic ignorance has been linked to a wide range of deleterious consequences. Victims of pluralistic ignorance see themselves as deviant members of their peer group: less knowledgeable than their classmates, more uptight than their peers, less committed than their fellow board members, less competent than their fellow nurses (see the Dunning–Kruger effect operating in the opposite direction). This can leave them feeling bad about themselves and alienated from the group or institution of which they are a part. In addition, pluralistic ignorance can lead groups to persist in policies and practices that have lost widespread support: This can lead college students to persist in heavy drinking, corporations to persist in failing strategies, and governments to persist in unpopular foreign policies. At the same time, it can prevent groups from taking actions that would be beneficial in the long run: actions to intervene in an emergency, for example, or to initiate a personal relationship.

Pluralistic ignorance can be dispelled, and its negative consequences alleviated, through education. For example, students who learn that support for heavy drinking practices is not as widespread as they thought drink less themselves and feel more comfortable with the decision not to drink. Alcohol intervention programs now routinely employ this strategy to combat problem drinking on campus.[27]

Misconceptions

Pluralistic ignorance can be compared with the false consensus effect. In pluralistic ignorance, people privately disdain but publicly support a norm (or a belief), while the false consensus effect causes people to wrongly assume that most people think like they do, while in reality most people do not think like they do (and express the disagreement openly). For instance, pluralistic ignorance may lead students to drink alcohol excessively because they believe that everyone else does so, while in reality everyone else also wishes they could avoid binge drinking but no one expresses that wish out of fear of being ostracized.[8] A false consensus for the same situation would mean that the student believes that most other people do not enjoy excessive drinking, while in fact most other people do enjoy that and openly express their opinion about it.

A study undertaken by Greene, House, and Ross used simple circumstantial questionnaires on Stanford undergrads to gather information on the false consensus effect. They compiled thoughts on the choice they felt people would or should make, considering traits such as shyness, cooperativeness, trust, and adventurousness. Studies found that when explaining their decisions, participants gauged choices based on what they explained as "people in general" and their idea of "typical" answers. For each of the stories those subjects said that they personally would follow a given behavioral alternative also tended to rate that alternative as relatively probable for "people in general": those subjects who claimed that they would reject the alternative tended to rate it as relatively improbable for "people in general". It was evident that the influence of the subjects' own behavior choice affected the estimates of commonness.[28] Although it would seem as if the two are built on the same premise of social norms, they take two very oppositional stances on a similar phenomenon. The false consensus effect considers that in predicting an outcome, people will assume that the masses agree with their opinion and think the same way they do on an issue, whereas the opposite is true of pluralistic ignorance, where the individual does not agree with a certain action but go along with it anyway, believing that their view is not shared with the masses (which is usually untrue).

See also

- Abilene paradox

- Asch conformity experiments

- Common knowledge (logic)

- Conformity

- Die Wende

- Glasnost

- Groupthink

- Mutual knowledge

- Peer pressure

- Political correctness

- Prisoner's dilemma

- Preference falsification

- Silent majority

- Spiral of silence

- Social norms approach

- Stag hunt

- Thomas theorem

References

- ^ a b Sparkman, Gregg; Geiger, Nathan; Weber, Elke U. (23 August 2022). "Americans experience a false social reality by underestimating popular climate policy support by nearly half". Nature Communications. 13 (1): 4779. Bibcode:2022NatCo..13.4779S. doi:10.1038/s41467-022-32412-y. PMC 9399177. PMID 35999211.

- ^ Yoder, Kate (29 August 2022). "Americans are convinced climate action is unpopular. They're very, very wrong. / Support for climate policies is double what most people think, a new study found". Grist. Archived from the original on 29 August 2022.

- ^ Bicchieri, Cristina; Fukui, Yoshitaka (1999). "The Great Illusion: Ignorance, Informational Cascades, and the Persistence of Unpopular Norms". Business Ethics Quarterly. 9 (1): 127–155. doi:10.2307/3857639. JSTOR 3857639.

- ^ Nickerson, Charlotte (May 11, 2022). "Pluralistic Ignorance: Definition & Examples". www.simplypsychology.org.

- ^ Miller, Dale T.; McFarland, Cathy (1987). "Pluralistic ignorance: When similarity is interpreted as dissimilarity". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 53 (2): 298–305. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.53.2.298. ISSN 0022-3514.

- ^ Katz, Daniel; Allport, Floyd Henry; Jenness, Margaret Babcock (1931). Students' attitudes; a report of the Syracuse University reaction study. Syracuse, N.Y.: Craftsman Press.

- ^ a b Schwenkenbecher, Anne (16 February 2021). "How We Fail to Know: Group-Based Ignorance and Collective Epistemic Obligations" (PDF).

- ^ a b Kitts, James A. (September 2003). "Egocentric Bias or Information Management? Selective Disclosure and the Social Roots of Norm Misperception". Social Psychology Quarterly. 66 (3): 222–237. doi:10.2307/1519823. JSTOR 1519823.

- ^ Prentice, Deborah A.; Miller, Dale T. (1993). "Pluralistic ignorance and alcohol use on campus: Some consequences of misperceiving the social norm". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 64 (2): 243–256. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.64.2.243. ISSN 1939-1315. PMID 8433272. S2CID 24004422.

- ^ Schanck, Richard Louis (1932). "A study of a community and its groups and institutions conceived of as behaviors of individuals". Psychological Monographs. 43 (2): i–133. doi:10.1037/h0093296. hdl:2027/umn.319510014995563.

- ^ O'Gorman, Hubert J. (October 1986). "The discovery of pluralistic ignorance: An ironic lesson". Journal of the History of the Behavioral Sciences. 22 (4): 333–347. doi:10.1002/1520-6696(198610)22:4<333::AID-JHBS2300220405>3.0.CO;2-X.

- ^ Miller, Dale T. (2023). "A century of pluralistic ignorance: what we have learned about its origins, forms, and consequences". Frontiers in Social Psychology. 1. doi:10.3389/frsps.2023.1260896. ISSN 2813-7876.

- ^ Noelle-Neumann, E. (1993). The Spiral of Silence: Public Opinion--Our Social Skin. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-58936-7.

- ^ Rose, Todd (February 2022). Collective Illusions: Conformity, Complicity, and the Science of Why We Make Bad Decisions. Hachette Books. ISBN 978-0-306-92568-9.

- ^ O'Gorman, Hubert J. (1975). "Pluralistic Ignorance and White Estimates of White Support for Racial Segregation". Public Opinion Quarterly. 39 (3): 313. doi:10.1086/268231.

- ^ a b Davis, TL; Laker, J. How College Men Feel about Being Men and "Doing the Right Thing." (PDF). Masculinities in Higher Education: Theoretical and Practical Implications.: Routledge, Kegan & Paul Publishers. pp. Ch. 10. Retrieved 4 September 2018.

- ^ Andersen, H.C. (1882). "The Emperor's New Clothes". Andersen's Fairy Tales. Collins' illustrated pocket classics. A.L. Burt Company. p. 4. ISBN 978-1-59377-472-1.

- ^ Geiger, Nathaniel; Swim, Janet K (September 2016). "Climate of silence: Pluralistic ignorance as a barrier to climate change discussion" (PDF). Journal of Environmental Psychology. 47: 79–90. doi:10.1016/j.jenvp.2016.05.002. Retrieved 4 September 2018.

- ^ a b Mildenberger, Matto; Tingley, Dustin (December 2017). "Beliefs about Climate Beliefs: The Importance of Second-Order Opinions for Climate Politics" (PDF). British Journal of Political Science. 49 (4): 1279–1307. doi:10.1017/S0007123417000321. Retrieved 4 September 2018.

- ^ Leiserowitz, A; Maibach, E; Roser-Renouf, C; Cutler, M; Kotcher, J. "Politics and Global Warming, March 2018" (PDF). Yale University and George Mason University. Retrieved 4 September 2018.

- ^ Marlon, Jennifer; Howe, Peter; Mildenberger, Matto; Leiserowitz, Anthony; Wang, Xinran. "Yale Climate Opinion Maps 2018". Yale Program on Climate Change Communication. Retrieved 4 September 2018.

- ^ Media, Everest (19 May 2022). Summary of Todd Rose's Collective Illusions. Everest Media LLC. ISBN 979-8-8225-1713-4.

- ^ Clifford, Catherine (August 24, 2022). "Americans don't think other Americans care about climate change as much as they do". CNBC. Retrieved August 27, 2022.

- ^ "Derren Brown: The Push | Netflix Official Site". Netflix.

- ^ Bursztyn, Leonardo; González, Alessandra L.; Yanagizawa-Drott, David (2020). "Misperceived Social Norms: Women Working Outside the Home in Saudi Arabia" (PDF). American Economic Review. 110 (10): 2997–3029. doi:10.1257/aer.20180975. ISSN 0002-8282. S2CID 224901902.

- ^ Schneider, Jillian (19 January 2023). "Americans are rethinking education priorities". The Lion.

- ^ Prentice, Deborah A. (2007-08-29). "Pluralistic Ignorance". In Baumeister, Roy F. (ed.). Encyclopedia of Social Psychology. Los Angeles: SAGE. ISBN 978-1-4129-1670-7.

- ^ Ross, Lee; Greene, David; House, Pamela (May 1977). "The "false consensus effect": An egocentric bias in social perception and attribution processes". Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 13 (3): 279–301. doi:10.1016/0022-1031(77)90049-X. S2CID 9032175.