Australopithecus deyiremeda

| Australopithecus deyiremeda Temporal range: Pliocene,

| |

|---|---|

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Primates |

| Suborder: | Haplorhini |

| Infraorder: | Simiiformes |

| Family: | Hominidae |

| Subfamily: | Homininae |

| Tribe: | Hominini |

| Genus: | †Australopithecus |

| Species: | †A. deyiremeda

|

| Binomial name | |

| †Australopithecus deyiremeda Haile-Selassie et al., 2015

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

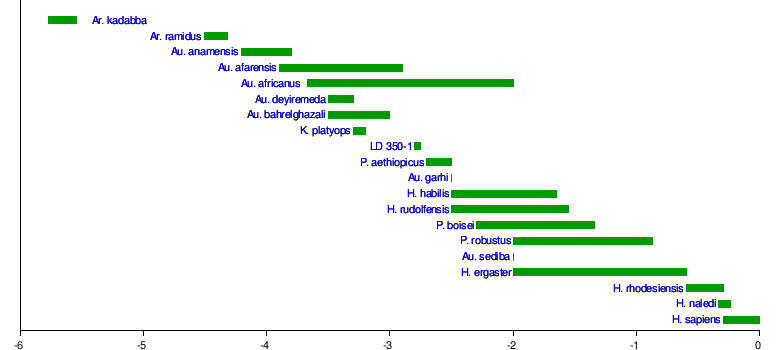

Australopithecus deyiremeda is an extinct species of australopithecine from Woranso–Mille, Afar Region, Ethiopia, about 3.5–3.3 million years ago during the Pliocene. Because it is known only from three partial jawbones, it is unclear if these specimens indeed represent a unique species or belong to the much better known A. afarensis. A. deyiremeda is distinguished by its forward facing cheek bones and small cheek teeth compared to those of other early hominins. It is unclear if a partial foot specimen exhibiting a dextrous big toe (a characteristic unknown in any australopith) can be assigned to A. deyiremeda. A. deyiremeda lived in a mosaic environment featuring both open grasslands and lake- or riverside forests, and anthropologist Fred Spoor suggests it may have been involved in the Kenyan Lomekwi stone tool industry typically assigned to Kenyanthropus. A. deyiremeda coexisted with A. afarensis, and they may have exhibited niche partitioning to avoid competing with each other for the same resources, such as by relying on different fallback foods during leaner times.

Taxonomy

Australopithecus deyiremeda was first proposed in 2015 by Ethiopian palaeoanthropologist Yohannes Haile-Selassie and colleagues based on jawbone fossils from the Burtele and Waytaleyta areas of Woranso–Mille, Afar Region, Ethiopia. The holotype specimen, a left maxilla with all teeth except the first incisor and third molar BRT-VP-3/1, was discovered on 4 March 2011 by local Mohammed Barao. The paratype specimens are a complete body of the mandible with all incisors BRT-VP-3/14, and a right toothless jawbone WYT-VP-2/10, which were discovered by Ethiopian fossil hunter Ato Alemayehu Asfaw [es]. A right maxilla fragment with the fourth premolar BRT-VP-3/37 was found 5 m (16 ft) east of BRT-VP-3/14, and it is unclear if these belonged to the same individual. The sediments were radiometrically dated to 3.5–3.3 million years ago to the Middle Pliocene.[1]

The describers believed the remains were distinct enough from the contemporary and well-known A. afarensis to warrant species distinction, and A. deyiremeda is counted among a growing diversity of Late Pliocene australopithecines alongside A. afarensis, A. bahrelghazali, and Kenyanthropus platyops. The name deyiremeda derives from the Afar language meaning "close relative" because, existing so early in time, they considered A. deyiremeda to have been closely related to future australopiths.[1] However, though the proposed distinguishing characteristics are apparently statistically significant, given how few specimens of A. deyiremeda exist, it is unclear if this indeed warrants species distinction or if these specimens simply add to the normal range of variation for A. afarensis. If it is a valid species, then it could possibly indicate some A. afarensis specimens are currently classified into the wrong species.[2][3]

Haile-Selassie and colleagues noted that, though it shares many similarities with Paranthropus, it may not have been closely related because it lacked enlarged molars which are characteristic of Paranthropus.[4] Nonetheless, in 2018, independent researcher Johan Nygren recommended moving it to Paranthropus based on dental and presumed dietary similarity.[5] Nygren also postulated that the Homo/Paranthropus split occurred at the same time as gorilla introgression (interbreeding) to the human line about 6 mya with the chimpanzee–human last common ancestor, based on apparently gorilla-like attributes in deyiremeda. Anatomical differences between the two genera would have been a result of different expressions of gorilla genes due to differences in habitat and diet. He also suggested that interbreeding between Paranthropus and gorillas continued until 3.3 mya–based on the divergence time between Pthirus gorillae lice, which only infects gorillas, and P. pubis, which only infects modern humans–and that Australopithecus and human ancestors remained reproductively isolated from gorillas.[5] Nygren also claimed in a predatory journal that he found a nuclear mitochondrial DNA segment (NUMT) on chromosome 5 in humans, gorillas, and chimps which diverged at the human/chimp split instead of the gorilla/human–chimp split, which he considered further evidence of his hypothesis.[6] None of his work has been subjected to scholarly peer review.

|

Anatomy

Despite being so early, the jaws of A. deyiremeda show some similarities to those of the later Homo and the robust Paranthropus. The jaw jutted out somewhat (prognathism) at perhaps a 39° angle, similar to most other early hominins. The cheekbone is positioned more forward than most A. afarensis specimens. Unlike A. afarensis but like Paranthropus, the walls of the cheek teeth are inclined rather than coming straight up. The upper canines are smaller than those of other Australopithecus, and are morphologically more like those of A. anamensis. The cheek teeth are quite small for an early hominin, and the 1st molar is the smallest reported for an adult Pliocene hominin. Nonetheless, the enamel was still thick as other early hominins, and the enamel on the 2nd molar is quite high and more similar to P. robustus. The jawbone, though small, is robust and more similar to that of Paranthropus.[1]

In 2012, a 3.4 million year old partial foot, BRT-VP-2/73, was recovered from Woranso–Mille. It strongly diverges from contemporary and future hominins by having a dextrous big toe like the earlier Ardipithecus ramidus, and consequently has not been assigned to a species.[7] Though more diagnostic facial elements have since been discovered in the area, they are not clearly associated with the foot.[1]

Palaeoecology

A. deyiremeda was likely a generalist feeder. If A. deyiremeda is indeed distinct from A. afarensis, then these two species may have exhibited niche partitioning given they cohabited the same area. Given dental and chewing differences, they may have had different dietary and/or habitat preferences, unless these differences were simply a product of genetic drift.[2][8] Much like chimps and gorillas which have more or less the same diet and inhabit the same areas, A. deyiremeda and A. afarensis may have shared typical foods when in abundance, and resorted to different fallback foods in times of food scarcity.[3]

The Lomekwi stone tool industry from northern Kenya is loosely associated with the Middle Pliocene Kenyanthropus based on an upper jaw fragment assigned to Kenyanthropus based on forward cheekbones, three-rooted premolars, and small first molar. Since these features are also exhibited in A. deyiremeda, anthropologist Fred Spoor suggested that A. deyiremeda was actually present at the site.[8] The Lomekwian is the earliest culture identified at 3.3 million years old, and the knappers flaked off pieces of cores made of basalt, phonolite, and trachyphonolite probably to use as a hammer to pound against an anvil.[9]

The Middle Pliocene of Woranso–Mille features grazing impalas, alcelaphins, and elephants, as well as browsing giraffes, tragelephins, and forest-dwelling monkeys. The feet of the bovid species do not seem to be specialised for any particular type of ground (such as wet, pliable, or hard), and the teeth of hoofed species indicates an equal abundance of grazers, browsers, and mixed feeders. These indicate a mixed environment features both open grasslands as well as forests probably growing on a lake- or riverside. Such a mosaic landscape is similar to A. anamensis and A. afarensis which seem to have no preferred environment.[10]

See also

References

- ^ a b c d Haile-Selassie, Yohannes; Gibert, Luis; Melillo, Stephanie M.; Ryan, Timothy M.; Alene, Mulugeta; Deino, Alan; Levin, Naomi E.; Scott, Gary; Saylor, Beverly Z. (2015). "New species from Ethiopia further expands Middle Pliocene hominin diversity" (PDF). Nature. 521 (7553): 483–488. Bibcode:2015Natur.521..483H. doi:10.1038/nature14448. PMID 26017448.

- ^ a b Spoor, F.; Leakey, M. G.; O'Higgins, P. (2016). "Middle Pliocene hominin diversity: Australopithecus deyiremeda and Kenyanthropus platyops". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B. 371 (1698). doi:10.1098/rstb.2015.0231.

- ^ a b Haile-Selassie, Y.; Melillo, S. M.; Su, D. F. (2016). "The Pliocene hominin diversity conundrum: Do more fossils mean less clarity?". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 113 (23): 6364–6371. doi:10.1073/pnas.1521266113.

- ^ Haile-Selassie, Y.; Gilbert, L.; Melillo, S. M.; et al. (2015). "New species from Ethiopia further expands Middle Pliocene hominin diversity" (PDF). Nature. 521 (14448): 483–488. Bibcode:2015Natur.521..483H. doi:10.1038/nature14448. PMID 26017448.

- ^ a b Nygren, J. (2018). "The speciation of Australopithecus and Paranthropus was caused by introgression from the Gorilla lineage" (PDF). PeerJ Preprints. 6: e27130v3. arXiv:1808.06307. Bibcode:2018arXiv180806307N. doi:10.7287/peerj.preprints.27130v3.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Nygren, J. (2018). "Hominin Evolution Was Caused by Introgression from Gorilla". Natural Science. 10 (9). doi:10.4236/ns.2018.109033.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Haile-Selassie, Y. (2012). "A new hominin foot from Ethiopia shows multiple Pliocene bipedal adaptations". Nature. 483: 565–570. doi:10.1038/nature10922.

- ^ a b Spoor, Fred (2015). "Palaeoanthropology: The middle Pliocene gets crowded". Nature. 521 (7553): 432–433. doi:10.1038/521432a. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 26017440.

- ^ Harmand, S.; et al. (2015). "3.3-million-year-old stone tools from Lomekwi 3, West Turkana, Kenya". Nature. 521 (7552): 310–315. doi:10.1038/nature14464. PMID 25993961.

- ^ Curran, S. C.; Haile-Selassie, Y. (2016). "Paleoecological reconstruction of hominin-bearing middle Pliocene localities at Woranso-Mille, Ethiopia". Journal of Human Evolution. 96: 97–112. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2016.04.002.

External links

- Human Timeline (Interactive) – Smithsonian, National Museum of Natural History (August 2016)