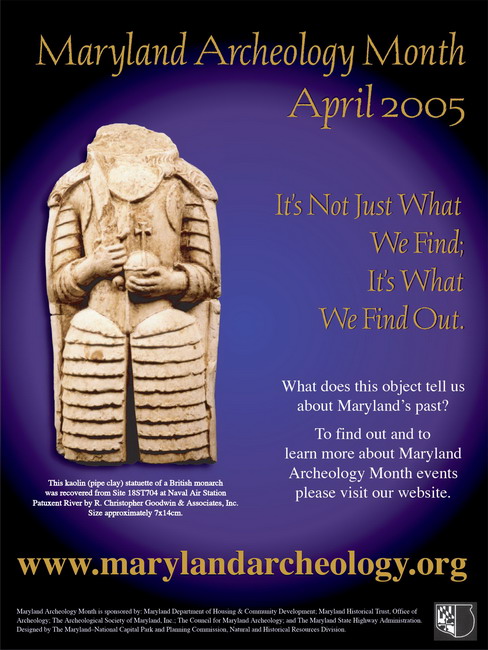

One of the more intriguing 17th-century artifacts found in Maryland is this ceramic figurine of a king (Figure 1). The broken artifact measures around 6 inches tall; originally the figurine would have stood about 10 inches in height (Grulich 2008). The headless monarch is clad in armor, holds a sword in his right hand and an orb topped with a cross in his left. The figurine, broken into two pieces, was found in 1998 at the Charles’ Gift Site (18ST704), on Naval Air Station Patuxent River. It had been deposited in a large trash midden containing ceramics dating its filling between 1682 and 1700 (Polglase 2001:179). The Charles Gift property was home at this time to Nicholas Sewall, stepson of Charles Calvert, governor of the Maryland colony. Cecil Calvert (1605-1675), the 2nd Lord Baltimore, established the Maryland colony, ruling it as its First Proprietor. His son Charles (1637-1715) was the 3rd Lord Baltimore and, unlike his father, lived in the colony that he governed.

Why would this figurine have found its way to the Maryland colony? There is some evidence that these figurines were produced as souvenirs of coronations and sold at fairs in England (Grulich 2008). It is possible that the Sewall family either purchased the figurine themselves, or had it shipped from England for display in their home. It may have been displayed in a room used for formal entertaining and signaled to visitors Sewall’s allegiance to the British throne.

Maryland prides itself on having been an early pioneer in the principles of religious toleration, welcoming Catholics, Puritans, Anglicans and Quakers. The colony’s proprietary government was often led by Roman Catholic governors closely tied to the Calvert family from 1634 to 1689. This religious tolerance marked the colony for the first five decades of settlement. But as the 17th century drew to a close, political events in England led to turbulent times in the Maryland colony. The 1689 Protestant Uprising sparked by the 1688 Glorious Revolution in England, which replaced the Catholic king with Protestant monarchs King William III and Queen Mary II, ended Catholic governance in Maryland. For the next two and a half decades, the Maryland colony was governed directly by the British crown.

Nicholas Sewall retained his loyalty to the Calvert family during the rebellion and fled from his home at Charles’ Gift to refuge in Virginia. He returned to his plantation only sporadically in the ensuing years. It is tempting to hypothesize that the headless king figurine may have been a victim of the political and religious turmoil. Is it possible that Sewall, after Catholic King James was deposed and replaced by Protestant monarchs, destroyed and discarded this depiction of the new royal authority? Or, was it damage and discard just the result of an unintended household accident? We will never know, but it is interesting to consider this object in light of the tumultuous early history of the colony.

There are several other 17th-century sites in southern Maryland where artifacts containing depictions of kingly figures have been recovered. Another broken white clay kingly figurine was found at the Middle Plantation site in Ann Arundel County (Grulich 2008). A fragment of a tin-glazed earthenware charger with a painted depiction of an unidentified royal figure was found at the Angelica Knoll site (18CV60) in Calvert County (Figure 2) and a complete German Hohrware jug with a portrait of England’s King William III was found at Westwood Manor in Charles County (Figure 3). Archaeologists who studied this site speculated that property resident John Bayne used this object, as well as stoneware tankards bearing the king’s initials and a set of framed likenesses of William and Mary listed in his estate inventory, to demonstrate his loyalty to the Protestant monarch and the Church of England at a time when the King had just supported the overthrow of the colony’s Catholic-run government (King, Arnold-Lourie, and Shaffer 2008; Alexander et al. 2010).

These kingly artifacts may be emblematic of the power struggles between Protestant and Catholic political factions in early Maryland. After the Protestant uprisings of 1689, religious toleration would not be regained in Maryland until the end of the 18th century. Regardless of their political and religious meanings, they hold a fascination for us today as enigmatic objects. In fact, the headless king figurine was the subject of Maryland’s 2005 Archeology Month poster – an entry which won a prize in the 2006 poster contest of the Society for American Archaeology.

References

Alexander, Allison, Skylar A. Bauer, Patricia H. Byers, Seth Farber, Alex J. Flick, Juliana Franck, Ben Garbart, Grace Gutowski, Julianna Jackson, Mark R. Koppel, Amy Publicover, Maria Tolbert, Verioska Torres, Alexandra Unger, Jerry S. Warner, Justin Warrenfeltz, Julia A. King, editor and Scott M. Strickland, researcher.

2010. The Westwood Manor Archaeological Collection: Preliminary Interpretations. Report prepared by the Archaeology Practicum Class, St. Mary’s College of Maryland, St. Mary’s City, Maryland.

Anne Dowling Grulich.

2008. An Enigmatic Monarch: The Biography of a Headless, Mold-made, White Pipe Clay King Recovered in 17th-Century Maryland. Website accessed May 12, 2020 at https://jefpat.maryland.gov/Documents/mac-lab/grulich-anne-dowling-enigmatic-monarch-biography-headless-mold-made-white-pipe-clay-king-recovered-in-17th-century-md.pdf.

King, Julia, Christine Arnold-Lourie, and Susan Shaffer

2008. Pathways to History; Charles County Maryland, 1658-2008. Smallwood Foundation, Inc., Mt. Victoria, Md.

Christopher Polglase.

2001. Phase III Archaeological Data Recovery at Site 18ST704 Naval Air Station Patuxent River, St. Mary’s County, MD. Final report by R. Christopher Goodwin & Associates, Inc., Frederick, MD. On file at the Maryland Archaeological Conservation Lab.