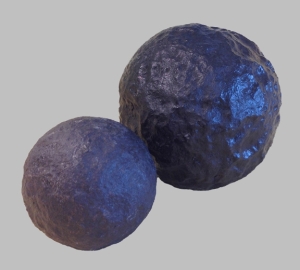

This 18 pound cannonball was donated to the Maryland Archaeological Conservation Lab several years ago by a nearby resident who found it on his property. Doubtless, this cannonball was fired during the Battle of St. Leonard’s Creek, where the British engaged with American Commodore Joshua Barney’s fleet in June of 1814 (Eshelman 2012). This month’s blog uses this artifact to commemorate the Battle of Bladensburg, which occurred on August 24, 1814.

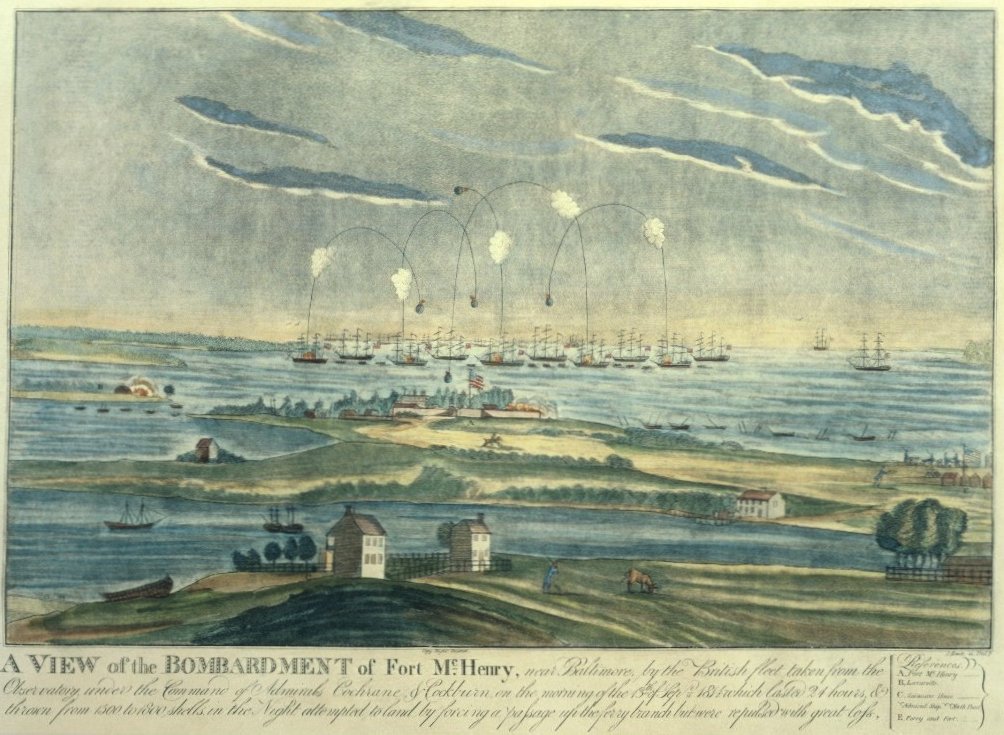

After British troops left Southern Maryland following the Battle of St. Leonard Creek, they advanced on Washington, D. C., with the goal of capturing the nation’s capital. American troops, anticipating this move, were waiting for them ten miles outside of the city, at Bladensburg. All signs pointed to an American victory: the American troops occupied the high ground leading into town, they controlled the bridge leading over the Anacostia River and they outnumbered the British forces 6,500 to 4,500 (Battlefields.org 2020). Three battle lines were drawn up along the high ground, with one of the lines consisting of sailors and marines under the command of Joshua Barney, who had recently engaged the British at St. Leonard Creek (Whitlow 2020).

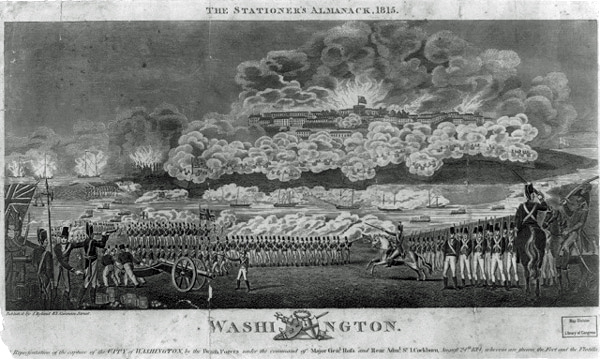

But the British forces had the advantage of more training and a strong, experienced leader in Major General Robert Ross (NPS 2016). Ross determined that the placement of the American troops left them vulnerable. Once the British troops had forded the river above the bridge, as well as forcing their way across the bridge, they advanced and gained control of the west bank of the river. American forces, under the command of General William Winder, quickly retreated. There were an estimated 450 casualties of the Battle of Bladensburg – 200 on the American side and 250 for the British troops. Commodore Barney was shot in the thigh, but managed to command his men to retreat before passing out from blood loss (Whitlow 2020).

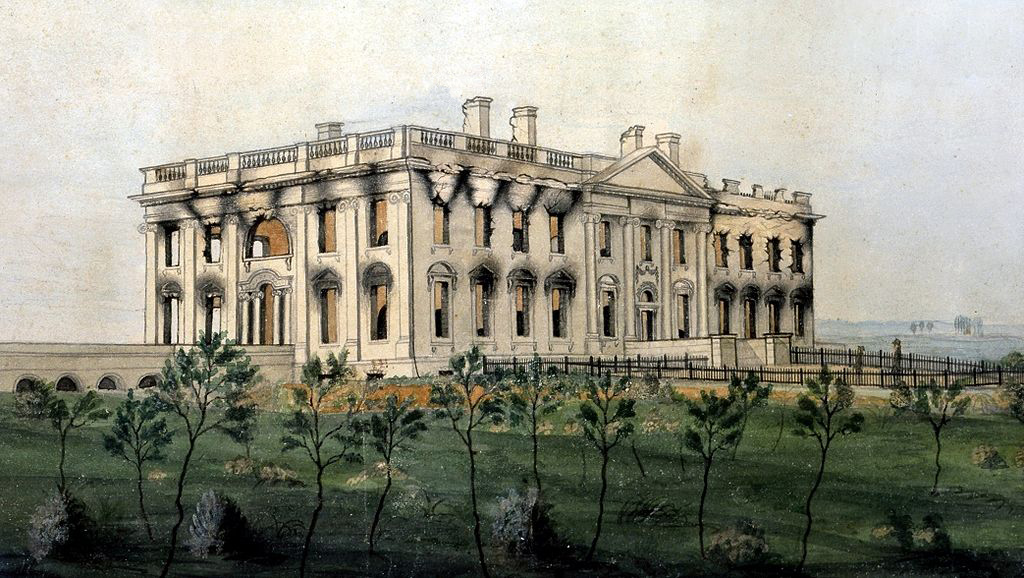

The British victory at Bladensburg allowed them to easily march into Washington, where they set fire to a number of public buildings, including the presidential mansion, occupied at that time by James and Dolley Madison. A dinner for forty people had been in the works when the mansion was abandoned and the soldiers partook of the food and wine before setting fire to the house (Gleig 1826). The capture of Washington on August 24th and 25th of 1814 was the only time a foreign power has captured our nation’s capital.

The Maryland State Highway Administration, in partnership with the Center for Heritage Resource Studies of the University of Maryland, conducted archaeological investigations at the Market Master’s House and the Indian Queen Tavern in Bladensburg as part of the outreach for the bicentennial celebrations of the War of 1812 (Crowl et al. 2012).

References

Battlefields.org. 2020. Bladensburg. American Battlefield Trust. Website accessed on August 21, 2020 at https://www.battlefields.org/learn/war-1812/battles/bladensburg.

Crowl, Heather, Benjamin Stewart, Carey O’Reilly, and Kathleen Furgerson. Bladensburg Archeological Investigations: Magruder House (18PR982), Market Master House (18PR983), and Indian Queen Tavern Site (18PR96), Prince George’s County, Maryland. 3 vols. SHA Archeological Report No. 432, SHA, Baltimore, 2012.

Eshelman, Ralph. In Full Glory Reflected: Discovering the War of 1812 in the Chesapeake. Maryland Historical Society, Baltimore, 2012.

Gleig, George Robert, A History of the Campaigns of the British at Washington and New Orleans (1826), reprinted in The Heritage of America by Henry Steele Commager and Allan Nevins (1939).

National Park Service (NPS). Summer 1814: American troops flee in humiliation, leaving Washington exposed. National Park Service. Website accessed August 18, 2020 at https://www.nps.gov/articles/bladensburg-races.htm.

Whitlow, Zachary. 2020. Bladensburg: Before the British Could Torch the Capital of the United States……They had one more stop to make. American Battlefield Trust Bladensburg. Website accessed August 21, 2020 at https://www.battlefields.org/learn/articles/bladensburg-british-could-torch-capital-united-states.