By Zachary Keith

The state of Tennessee is an ever-changing entity, evidenced by the creation and dissolution of counties. Throughout the state’s history, lawmakers renamed some counties, proposed many others that never formed, and created some that they later abolished. James County is the most recognized of these “lost counties” of Tennessee. Established in 1871, James County existed for 48 years until a referendum dissolved it in 1920.

Tennessee’s second state constitution of 1835 established guidelines for the creation of new counties in Tennessee. Following the enactment of a third state constitution in 1870, lawmakers made several changes affecting the procedure for establishing counties, including a reduction in the size threshold of each county, and an increase in the population threshold. The new regulations included:

- New counties had to be at least 275 square miles.

- Their populations had to be at least 700.

- No part of a new county could be less than 11 miles from adjacent county seat, with exceptions.

- Existing counties could not be reduced to less than 500 square miles, with exceptions.

- Two-thirds of the qualified voters within the proposed area of a new county had to agree to its formation.

|

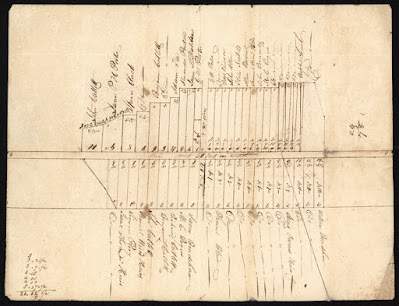

An Act to establish the county of James from parts of Hamilton and Bradley, 1871.

Tennessee State Library & Archives |

Predominately white, rural, and poor, James County arose out of the political factionalism of the Reconstruction Era. In 1871, Representative Elbert A. James, a Democrat from Hamilton County, introduced legislation for the formation of the county, named in honor of his father, Rev. Jesse J. James. The elder James, a Methodist minister from Sullivan County, first moved to Chattanooga in the 1850s. Three days after Rep. James introduced his bill, the Tennessee General Assembly passed the act creating James County on Jan. 30, 1871. Lawmakers chose Ooltewah as the county seat, and subsequently citizens began work on building a county courthouse. Following 19 years of meager existence, state lawmakers passed an act on March 11, 1890 abolishing the county and returning the land to the parent counties of Hamilton and Bradley. The legislation specifically mentioned the indebtedness of the county government as the reason for the return to the old boundaries.

|

An Act to abolish the county of James and restore the territory to the counties of Bradley and Hamilton, enacted March 11, 1890.

Tennessee State Library & Archives |

The commissioners of James County, upset with the General Assembly’s actions, filed legal action against the abolition. In

James County v. Hamilton County and Bradley County, they argued that the state legislature did not have the power to abolish a county without consent of the qualified voters of the county, and that the “radical legislation” should be overturned. The case made it to the Tennessee Supreme Court where Justice Peter Turney, future Governor of Tennessee, argued that Article X, Section 4 of the new (1870) State Constitution outlined that the “only authority conferred is to build up, and not pull down. It is equally apparent that it never occurred to the framers that a county could be destroyed or dissolved by an arbitrary Act of the Legislature.” He concludes with, “To abolish a county and give its territory to others, is to take from the one and add to the others without the consent of the people to be affected… The act is void.” Turney’s argument was that since the Tennessee Constitution of 1870 didn’t specifically outline the dissolution process for a county that the ultimate power resided with the citizens rather than the legislature.

|

| James County v. Hamilton County and Bradley County, from the Tennessee State Supreme Court Records. |

With the Supreme Court ruling, James County survived for another 29 years. However, low tax revenues and a crumbling education system forced the General Assembly to reconsider the county’s existence once more. On April 15, 1919, lawmakers passed an act abolishing James County, pending approval of its citizenry. The fate of James County rested with the voting populace, with a referendum determining the matter scheduled for Dec. 11, 1919.

|

An Act to abolish the county of James and restore the territory to the counties of Bradley and Hamilton, enacted April 15, 1919.

Tennessee State Library & Archives |

|

The Chattanooga News article from December 10, 1919, the day before the annexation referendum.

Tennessee State Library & Archives |

Chattanooga newspapers published the unofficial results of the voting on December 12, 1919.

The Chattanooga News reported 941 votes in favor of abolition and 77 against. Three days later, local election commissioners reported the official results to the Tennessee Secretary of State, Ike Stevens, recording 953 votes for abolishment, and 78 against. In the final tally, “more than two-thirds of the qualified voters in James County voted in favor of the abolishment of the county.”

|

Letter reporting the official December 11th referendum results to the Tennessee Secretary of State, RG 87, Election Returns (State, County, & Local), 1796-present.

Tennessee State Library & Archives |

With this vote, James County ceased to exist. After 48 years, the counties of Hamilton and Bradley absorbed James County and its government on January 5, 1920. The plight of James County, perhaps more than any other county in Tennessee, proved how important the formation of counties is to understanding Tennessee history. Marriage, birth, and death records from the period, as well as World War I records, all show James County, yet without knowing its history, researchers can become confused. Thankfully, some of James County’s records have survived various fires, and are presently kept by Hamilton County. The Tennessee State Library & Archives also holds the microfilm copies of James County records, available for use by scholars, genealogists, and researchers.

|

Photograph of the James County Courthouse in Ooltewah.

Tennessee State Library & Archives |

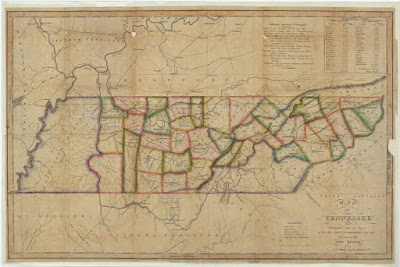

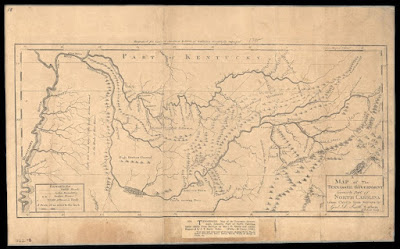

Visit "Maps at the Tennessee State Library and Archives" online at

http://share.tn.gov/tsla/TeVAsites/MapCollection/index.htm to learn more.

The Tennessee State Library and Archives is a division of the Tennessee Department of State and Tre Hargett, Secretary of State