Is this the last chance to see the Titanic?

Getty Images

Getty ImagesDeep-sea bacteria are quickly consuming the Titanic. One company is offering tickets to visit it one last time – and to help measure its deterioration.

Renata Rojas paddled behind her father through the water off the coast of Cozumel, Mexico. She was only five years old; never before had she been allowed out this far. Now, as she glided across the waves, her father stopped her and told her to look down to the sea floor. There, illuminated by the sunlight, was a sunken plane. She breathed through her snorkel as she studied its wings resting on the white sand.

It was in this moment that she discovered an eternal love for the ocean. “It’s almost like space opens up. It’s very serene,” she remembers today, decades later.

In 2019, following a lifetime of scuba training and saving money, Rojas is scheduled to fulfil her grandest dream: visiting the wreck of the RMS Titanic.

This is a dream that has become increasingly urgent over the years. Rust-forming bacteria are rapidly consuming the Titanic. Experts predict it will last only a little more than 20 years. That means that the group of select paying passengers which Rojas is joining won’t only be the first to lay eyes on the wreck since 2005, they will also be among the last to see it at all.

And while the expedition is a commercial venture, it is a scientific one too: the group will use advanced 3D-modelling tools to analyse and preserve the memory of the Titanic for generations to come.

You might also like:

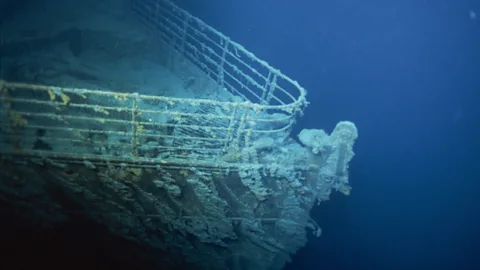

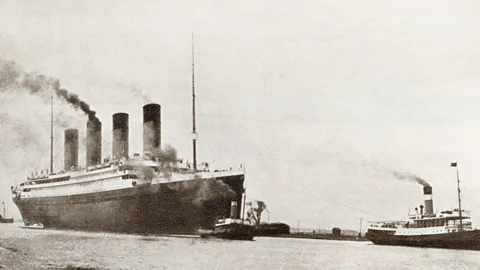

The Titanic struck an iceberg on 14 April 1912 as it steamed across the Atlantic on its maiden voyage from Southampton to New York City. It split in two and sank to a depth of 3.8km (2.5 miles) about 600km (370 miles) off the shores of Newfoundland, Canada. At least 1,500 people died. Engulfed by deep-sea darkness, the wreck sat for more than 70 years while bacteria ate away at its metal hull, leaving behind millions of delicate, icicle-shaped formations.

“Now, there’s more life on Titanic than there was floating on the surface,” says Lori Johnston, microbial ecologist and a six-time visitor of the wreck.

These ‘rusticles’ are the by-products of bacteria that oxidise the iron they consume. The acidic, oxidised fluid oozes downward with gravity, forming fragile branches of rust. “The rusticles are unique because they’re kind of the dominant species down there,” Johnston says.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesBy the time explorer Robert Ballard and his team discovered the ship in 1985, the rusticles had already taken over. Because they eat about 180kg (400lbs) a day, scientists have given the ship a waning life expectancy. “If it’s going faster, which we hypothesise, it’s going to be less and less of a timeframe,” says Johnston. According to her research, Titanic might be a recognisable shipwreck for just 20 to 50 more years.

Last chance

As the clock ticks down, the window of opportunity to visit the Titanic, for scientific purposes or otherwise, is quickly vanishing. One new opportunity is with OceanGate, a private company that uses its small fleet of manned submersibles to explore, research and catalogue the oceans surrounding North America. OceanGate has undertaken 13 expeditions since its founding in 2009, including surveys of other shipwrecks like the Andrea Doria near Nantucket and the SS Dix in Puget Sound. Not until the 2019 Titanic expedition, however, have they welcomed paying passengers who don’t have distinct expertise in marine science or research.

Chosen “mission specialists”, as OceanGate calls them, will embark on 11-day journeys in groups of nine beginning late June 2019 and ending mid-August. They will fly from St John’s, Newfoundland via helicopter to rendezvous with a support ship at sea, which will be their home base during the mission. Most importantly, they will be able to join at least one submersible dive to the Titanic.

Down below, while crammed together inside the newly-updated Titan submersible, mission specialists will aid the crew in using sophisticated lasers, sonars and imaging technology to composite the most detailed and accurate 3D model of the ship in history. A ticket for the 11-day excursion and all of its amenities costs $105,129 (£81,300) – equivalent to the cost of first-class passage on the Titanic’s fateful voyage in 1912, adjusted for inflation.

At first, the idea of non-professionals sinking to the bottom of the ocean – where the water temperature is 1C (34F) and the pressure is strong enough to crush them like a tin can – seems alarming. But to Joel Perry, president of OceanGate Expeditions and a diver for close to 30 years, safety is no issue. “It’s certainly not as dangerous as it might appear; we don’t just take anybody with us,” he says. “We go through a fairly rigorous process to screen folks and make sure they are appropriate.”

Perry says there is an explicit understanding that the applicants must be physically and mentally suitable for a week at sea. “Think about, is this somebody you want to be in the car with for eight hours with the windows rolled up?” In addition to a generally affable personality and proven physical fitness, all mission specialists will have to go through four hours of ‘helicopter egress training’ (learning what to do in the case of crashing) before departure. They’ll practice in a sinking helicopter cockpit in a large pool.

The applicants they accept are ones with track records like Rojas’, or as Perry calls her: “client number one”. “She’s had a passion for ocean exploration and the Titanic forever. Her nickname in the diving world is Mighty Mouse,” he says.

The first indicator, and perhaps the most crucial, is her long history of diving experience. Even as a young adult, Rojas shocked her instructors with courage in the face of crisis.

Getty Images

Getty Images“One of my first times diving alone without my dad, I had an emergency,” Rojas says. “I went into a hole and broke an air valve.” Her regulator, which attaches to the air tank, hadn’t been properly maintained. The O-ring inside the attachment exploded, letting out her air while she was 18m (60ft) underwater. Rather than lose her cool, however, Rojas swam to her instructor and borrowed some air from his tank. “He’s asking if I’m okay and I said ‘yeah, I want to keep diving.’ Most people panic and surface.” From free dives in the Caribbean and Arctic to advanced cave diving and even centrifuge training – the kind used by astronauts to familiarise themselves with the effects of G-force – Rojas’ seasoned repertoire is something OceanGate hopes to find in other expedition candidates.

The other trait that makes Rojas such an ideal mission specialist is her lifelong passion for everything Titanic. For her, it all began with the black-and-white film from 1953, which she first saw as a child. Her fascination with the glamour of the ship and the mystery of its tragic demise never left her. Even today, she proudly collects piles of Titanic books, magazines and newspaper clippings in her New York City home. “I’ve seen every movie, not read every book,” she admits. “I’ve probably missed a few.”

When the wreck was discovered in 1985, Rojas immediately changed her career to oceanography and began saving money for her own trip. She met Ballard himself, but the explorer told her that no-one would be making another expedition to the site. She was crushed. She returned to her previous job, banking.

Two years later, she watched on television as William F Buckley emerged from a submersible following his own Titanic voyage. “He wasn’t an oceanographer,” Rojas says. “He was just a millionaire.” She knew then: Ballard was wrong. With the right organisation and funding, visiting the wreck was still possible.

It wasn’t until 2012, nearly 30 years after Titanic was found, that Rojas was able to secure a ticket on a commercial dive with Deep Ocean Expeditions (DOE). It would be a centennial journey, a sombre yet uniquely special chance to honour the 100th anniversary of the ship’s sinking. Rojas sent emails to DOE every few weeks to make sure everything was on schedule. But in February, just two months before departure, the trip was cancelled. “I cannot even describe the sadness,” Rojas says. “It took me about a year to get a grip and start thinking about it again.”

Surf war

The prospect of visiting the Titanic wreck has been controversial since its discovery. According to David Concannon, an expedition leader and attorney who has represented OceanGate in the past, Ballard and his French crew began arguing over jurisdiction and access less than 24 hours after they surfaced in 1985. The back-and-forth resulted in Ballard spearheading the creation of an international agreement to leave the wreck alone – which the French promptly ignored.

Ever since, the governments of Britain, France, the US and Canada have been locked in a turf war against private individuals and companies like OceanGate seeking to visit Titanic.

“It has always been about control,” says Concannon, who currently advises OceanGate. “Who gets to control the site, the recovery of artefacts, the filming, and the battles over the last 30 years have been about control. And when you look at it that way, the smoke begins to clear.” Today, Concannon calls the guidelines and restrictions from Noaa (the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration) and others “draconian”. For their part, Noaa believe that Titanic visits, even ones that don’t seek to salvage artefacts, are disturbances to its architectural integrity and to its status as an underwater cultural heritage site and memorial.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesFortunately for OceanGate, however, there is not much in the way of enforcing Noaa’s rules. Threats of legal retaliation have been tested in the past, never with any real follow-through. “If they try to impose restrictions, no-one’s going to adhere,” Concannon says. “They’re just going to show up, dive, do what they want, and leave.”

This oceanic free-for-all is made easier because of how far the wreck is from the Canadian shore. Territorial water boundaries stop at 19km (12 miles) and economic boundaries at 160km (100 miles), Concannon says. The Titanic is 600km (370 miles) away from Newfoundland. In other words: in the high seas.

Despite bristling at Noaa’s guidelines, Perry says OceanGate intends to follow them. Their mission in 2019, other than giving participants the trip of a lifetime, is to use 3D-mapping technology to capture the wreck in its entirety for the first time in 10 years. The Titan submersible will be outfitted with sonars and laser scanners courtesy of media company Virtual Wonders to capture billions of spatial data points from the Titanic. The result, after a pass through a liquid-cooled super computer, will be an ultra-high-resolution 3D model unlike anything made before. “What we’ll get this year is the bow section in great detail, and the aft section in good detail,” says CEO Mark Bauman. “It’s going to take years to map the interior. Each year we’ll get better and better.”

By making multiple passes over the ship during OceanGate’s six-week expedition schedule, Bauman says they might even be able to see the volumetric change from the bacteria happen in real time. “This should give us something to triangulate it against the last measurements that were made on the Titanic. It should allow us to time the projections of when the Titanic will just be a rust stain on the floor.”

Perry says the 3D models and data will be given freely to scientists and researchers who wish to use them in their work, an approach consistent with how Noaa have treated their own visual content from the wreck. A portion of the material will also be made available for education and outreach purposes through the company’s non-profit, OceanGate Foundation.

For everyone else, Bauman hopes to create immersive experiences for different entertainment mediums. “We plan to put out AR apps and VR apps, we plan to probably sell it into video games, people will be able to fly the sub down themselves,” Bauman says. “It’ll look better than 3D Imax resolution.”

OceanGate’s mission specialists will help to collect this data from both inside the submersible and aboard the support ship, a novel concept that specifically attracted Rojas to the journey. She has eagerly tracked the company’s progress ever since she met them five years ago. “I want to be involved in everything, but mainly submersible operations or communication with the surface,” she says. “We are not tourists. We are actually part of the crew.” If she’s lucky, Rojas will even be able to pilot the sub using its unique steering wheel: a wireless PlayStation game controller. “I’m putting all my bets with OceanGate. I do believe they will be successful.”

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIt’s for this reason that Rojas feels the steep price of a ticket is worth every penny. Not only will she witness a site seen only by a handful of people, but she will be directly involved in every inch of the journey. For her and the other committed applicants, it’s all too good to pass up. Besides, she points out, a space flight is going for $250,000 (£190,000); an Everest trek can be $90,000 (£70,000). This, Perry says, “felt like the right number for the market”.

Deep dive

If all goes to plan, then in June 2019, Rojas will transfer from the support ship and climb down the ladder into the Titan from the top hatch. After taking her seat beside the other specialists, the hatch will close, and the sub will slowly descend into the blackness. She will hear the clicks and buzzes from inside and watch as condensation forms on the walls.

When she finally touches down, the lights will turn on and she’ll be face to face with her dream: the Titanic in all of its ruined glory. “I’m going to feel very overwhelmed. After waiting for so long, I’m able to actually be in front of the shipwreck itself,” she says. “I also think it’s going to be a very sombre moment. The tragedy itself is a very sad event. It’s going to be emotional for me in both aspects.”

“It is a gravesite,” Johnston says. “You have this moment of where you are and what you’re seeing. We are immensely respectful of that.” Some, including descendants of Titanic survivors, argue that visiting the wreck is a form of disrespect to the hundreds that perished in 1912. But to Johnston, doing so can create unique learning opportunities for generations that will come long after the ship is gone. It includes “everything from geography to oceanography to deep oceans to history to archaeology,” she says. “It’s part of history, so you want to bring that history to the people.”

Rojas hopes to share her own insight from the journey with children as well. She wants them to know that a lifelong dream, even one like hers, is always in reach. “I was a kid one day who had a dream. If they have a dream and it seems big and insurmountable, they can make it happen,” she says. “I’m prepared to go.”

--

A previous version of the story had date of the Titanic's sinking as 12 April.

If you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called “If You Only Read 6 Things This Week”. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Capital, and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.