Japan has an excess sushi problem. These food waste activists put it in numbers

Rachel Nuwer

Rachel NuwerThe country's ubiquitous convenience stores throw out huge amounts of edible food. In Tokyo, Rachel Nuwer meets the campaigners trying to change that.

Riko Morinaga, a recent high school graduate in Tokyo, normally spends her weekend nights hanging with friends. But 3 February was different. That Saturday night was Setsubun, a Japanese holiday celebrating the transition into spring. It also happens to be one of Japan's biggest food waste days.

Every year on Setsubun, stores across the country stock a holiday sushi roll called ehomaki. At the end of the night, hundreds of thousands of these rolls wind up in the garbage. "Shops always provide what customers want, which means their shelves have to always be stocked," Morinaga says. "This contributes to the food loss problem."

Last Setsubun, Morinaga and a dozen other volunteers visited 101 convenience stores across Japan to record the number of ehomaki rolls left on shelves after 21:00. The amounts were staggering. When Morinaga stopped by a FamilyMart near Shibuya train station at 21:06, she counted 72 rolls. At a 7-Eleven at 21:18, she found 93 rolls.

Based on the data Morinaga and others gathered, Rumi Ide, an independent researcher, activist and journalist who coordinated the survey, extrapolated that Japan's 55,657 convenience stores threw out 947,121 ehomaki rolls worth 700-800m yen ($4.5-5m; £3.6-4.1m). Ide published these results on the news website Yahoo Japan (unavailable in UK and Europe) to raise awareness about this hidden problem.

Rachel Nuwer

Rachel NuwerMore than a one-off issue, ehomaki sushi rolls have become emblematic of the wider problem of food waste in Japan. They have also come to epitomise how the country's ubiquitous convenience stores – known for their dependable supply of perishable food items like sushi, sandwiches and pre-made dinners – play an outsized role in contributing to the issue. Many of these stores stay open 24 hours, 365 days a year, and behind the convenience, Ide says, "lies a huge amount of waste, which consumers are unaware of".

On the evening I visited several Tokyo convenience stores with Ide and Morinaga, the shelves, as usual, were packed with onigiri (rice balls), sandwiches, salads, microwave meals and sweets. While some of these foods would find homes before the night's end, the late hour meant that many would likely be tossed into the bin, Morinaga says. "Part of the problem is that we've normalised throwing food out."

The exact size of the problem is difficult to quantify, because convenience store companies usually are not transparent about their losses. Representatives from 7-Eleven Japan and Lawson, two major chains, told BBC.com that they do not disclose the amount of food waste generated by their stores. Representatives from FamilyMart, another major chain, did not respond to interview requests, but the company indicates on its website that its stores generate 56,367 tonnes of food waste per day. In 2020, the Japan Fair Trade Commission estimated that Japan's major convenience store chains throw away on average 4.68m yen ($30,000; £24,000) of food per shop per year – equating to an approximate annual loss of more than 260bn yen (1.7bn; £1.3bn) in total.

"It's crazy that we're throwing away so much," Ide says. This is especially true, she adds, given that Japan imports Japan imports 63% of its food from abroad. In addition to the wasted money and resources food loss represents, it also contributes to climate change through emissions from production, transport and disposal (in Japan, rubbish is primarily incinerated).

As part of its commitment to the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals, Japan has pledged to halve the country's food waste to 4.9 million tonnes by 2030, compared to the 9.8 million tonnes generated in 2000. Things are trending in the right direction: edible food waste has dropped from up to 6.4 million tonnes in 2012 to 5.23 million tonnes in 2021. However, some activists say that Japan is still not doing enough. For one, the Sustainable Development Goal related to food loss and waste specifies that countries should set targets based on 2015 levels. By backtracking to 2000, when the rate was higher, the Japanese government is taking "a cheating approach", Ide says.

She and others want more significant reform – targeting convenience stores' food waste as a critical first step. While some of the solutions needed to address this problem are unique to Japan, others could be applied in countries around the world.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe cost of convenience

Ide's eyes were opened to the pernicious problem of food waste in 2011, when the Fukushima nuclear power plant disaster struck. She was working at the time for Kellogg Japan and her boss tasked her with coordinating aid donations to evacuation centres. She was shocked to find that the food brought to shelters often wound up in the garbage rather than reaching those in need. At one point, volunteers delivered thousands of bento lunchboxes and bread products, but because of various bureaucratic concerns, she says – including a lack of standardisation across meals – much of the food was never distributed. "I couldn't understand why," Ide tells me, shaking her head. "It was ridiculous."

The incident inspired Ide to dig deeper into the problem. She was so incensed by what she found that she resigned from Kellogg to work full-time on solving food loss. More than a decade later, virtually everyone in Japan who is interested in this problem is familiar with Ide through her media appearances, books, articles and seminars she holds around the country. As Morinaga says, "she is a very famous person."

For convenience store officials, though, Ide's criticisms have made her "one of the most disliked persons in the country", says Masafumi Kawano, a 7-Eleven employee who chairs an employee union with members from 7-Eleven and other convenience store chains.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIde is not alone in her commitment to solving this issue, though. She works with a large network of concerned citizens and industry insiders who are equally motivated to reform the system, and who have helped piece together how murky industry practices contribute to food waste.

Sakura Kinjo, another recent high school graduate who Ide works with, for example, was so interested in food waste that she got a part-time job at a small branch of a major convenience store chain in Osaka to gather intel (she asked not to reveal the name of the chain she works for). Around an hour before closing, she says, she and her colleagues begin removing food from shelves – usually, about 50-70 products per day, including sushi, bento boxes, onigiri, sandwiches and sweets. Seeing all that needless waste, she says, "makes my heart ache".

All of the food she removes from shelves is destined for the garbage, yet when that happens, it's all still perfectly fine for eating. That's because food is taken off shelves not when it expires, but somewhere between production and expiration – a strategy meant to ensure freshness for customers. "Some products you throw away three or four days before the expiry date," Kinjo says. Employees are not allowed to eat or take home any of the food destined for disposal, she adds, because shop owners want their workers to pay for food. (Once, she did sneak a rice ball out of the garbage bag and "ate it out back so no one would see".)

Extra cost of waste

Consumers are doubly burdened for the cost of prematurely removing food from store shelves, Ide says, including through higher prices built in to buffer against the inevitable losses, and taxes paid to cover local garbage incineration. "If people recognised that they spend a lot of money on food waste, I think their minds and attitudes would change," Ide says.

The personal economics of food waste might not be obvious to most consumers, but for convenience store franchise owners, it is salient. Merchants purchase food from headquarters and bear the majority of the cost for anything wasted. A spokesperson for 7-Eleven confirmed that their merchants cover 85% of food waste costs while headquarters covers just 15%. Because merchants pay headquarters for all the items they stock, Masafumi adds, regardless of whether the item is sold or thrown out, headquarters makes a profit. The 7-Eleven spokesperson denied this was the case. "Even if a large amount of food is supplied to a store, the profit of the head office will not increase unless customers purchase the food," he said.

Rachel Nuwer

Rachel NuwerA version of this so-called "convenience store accounting system" is used by all of Japan's convenience store chains, and according to Ide, it drives food wastage because it incentivises headquarters to push franchises to over-order. "The main offices make more profit as they supply more food to the stores, regardless of whether it's wasted," agrees Kawano, from the employees' union. "From the viewpoint of the main office, waste is still profit."

Store owners say they face pressure to over-order daily items, Kawano says, and also to sell more seasonal items, year by year. In preparation for Setsubun, for example, Kawano claims that 7-Eleven headquarters sent out a notice in December encouraging all of its franchises to order 1.5 times the number of ehomaki sold the previous year. The same happens for Christmas cakes, he says, usually eaten in Japan on 24 or 25 December. "Every year, headquarters sets a [higher] target for Christmas cakes" compared with the year before, Kawano says. "That number must be met."

Some merchants buy leftover seasonal items personally to minimise apparent waste and hit their numbers. One union member told Kawano about having to buy around 100 ehomaki rolls; another brought home 25 Christmas cakes. They did this to avoid being berated by headquarters, Kawano says, and out of fear of having their contracts terminated. The pressure to perform can also take a serious mental health toll. Kawano says he's known several store managers who have died by suicide, including a 27-year old colleague who failed to sell enough oden, a simmered savoury dish sold in colder months. "It was his first year in the job, and he had been reprimanded for not achieving his target," Kawano says. "He felt very responsible for that."

A 7-Eleven Japan spokesperson denied the existence of any quotas for its franchises. While Kawano agrees that merchants are not technically obliged to follow headquarters' instructions, he says that, in reality, most do. "It's a power structure thing," he says. "When the main office says something, the branches are almost forced to obey."

A few convenience stores are, however, trying to do things differently.

Experiment in store

In Tokyo's Toshima ward, there's a convenience store unlike its counterparts. On the surface, it's part of the Lawson convenience store chain – originally a US company but now headquartered and operating across Japan – but astute customers will notice something different about it. At this location, which I visited on a rainy spring day, the company's usual bright blue and white lettering has been replaced with exuberant rainbow splotches that are colour-coded to match the UN's Sustainable Development Goals. As I step through the sliding glass doors, a chipper robotic greeter inside offers an explanation in Japanese: this is the company's flagship "Green Lawson", an experimental shop that aims to reduce waste.

Rachel Nuwer

Rachel Nuwer"We want to show what convenience stores could do for reaching the [Sustainable Development Goal] targets," says Yayoi Sugihara, Lawson's senior manager of corporate communications. She and her colleagues have deployed a mix of solutions to try to hit these targets, she says, including "some drastic approaches".

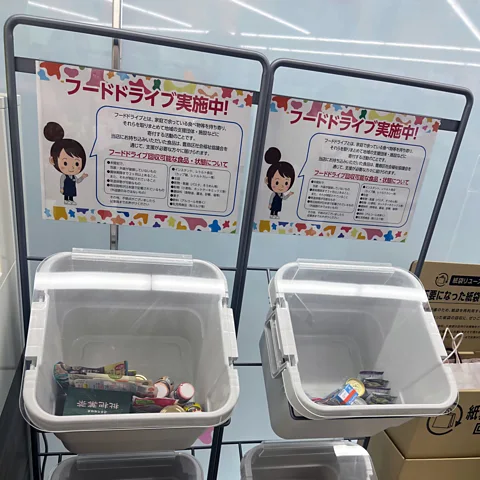

The quantity and types of fresh foods that staff stock on shelves, for example, is determined by an artificial intelligence system whose predictive algorithm includes factors like weather forecasts, current events and past sales. The AI also decides when to issue discounts to try to move items off shelves that aren't selling. Other solutions are lower tech. Rather than the usual open fridges and freezers, for example, doors keep the coolness in. The store recycles its extra cooking oil and gives its food waste to a local biogas company, and customers get a small discount if they bring their own coffee cup. They can also donate paper shopping bags to a community rack for others to use, and bring non-perishable items for a foodbank for those in poverty (the shop itself does not contribute to the bin, however).

Rachel Nuwer

Rachel NuwerSign up to Future Earth

Sign up to the Future Earth newsletter to get essential climate news and hopeful developments in your inbox every Tuesday from Carl Nasman. This email is currently available to non-UK readers. In the UK? Sign up for newsletters here.

It's had teething problems, though. Some customers "are not happy" about the store's lack of plastic bags or free single-use cutlery, Sugihara says. They can buy disposable bamboo cutlery instead – but I notice that it's wrapped in plastic, as are many of the items in the store. The AI system also struggles sometimes to hit the sweet spot between reducing food waste and stocking enough sushi and sandwiches to provide an attractive selection. "People avoid empty shelves, so there's a conflict there," Sugihara says.

More like this:

• The unique culture of Japanese convenience stores

Thanks in part to the somewhat lacklustre customer support, Lawson's headquarters, for now, does not plan to open additional Green Lawsons. But Sugihara adds that other stores are "doing bits and pieces" to try to reduce food waste, including by offering more frozen items, giving discounts for foods nearing the end of their shelf life and participating in a government-sponsored campaign that encourages customers to select foods at the front of the shelf. By applying these and other methods, Sugihara says that Lawson has reduced food loss across the board by 23% between 2018 and 2022.

In Ide's opinion, Lawson is the most progressive of Japan's convenience store chains. Other companies have been slower to change, although there are some positive developments. Like Lawson, 7-Eleven has begun encouraging its franchises to issue discounts for food nearing its expiration, according to a spokesperson. This is a significant departure from the company's previous policy, Kawano says, which banned most price reductions.

Some positive developments are also happening in legislation. In 2019, Ide's lobbying contributed to Japan's government passing the Food Loss and Waste Act, which encourages national and local governments to find solutions to tackle food waste. It isn't perfect, though. For example, the Act encourages businesses to donate non-expired products to food banks, but companies often hesitate to do so because they are liable if anyone is sickened by their donations. One way to get around this, Kinjo says, is to create a Japanese version of the Bill Emerson Good Samaritan Food Donation Act, a US law passed in 1996 that provides protection for food donors. Kinjo started law school at Kwansei Gakuin University in April, but she is already taking concrete steps to move Japan toward similar legislative changes: she's reached out to food banks, food companies, city halls, lawyers and politicians to invite them to form a working group to discuss the issue.

Changing the economics of food loss at convenience stores could also reduce waste, Ide says. However, representatives at Lawson and 7-Eleven confirmed to BBC.com that neither company is considering changes to the convenience store accounting system. Kawano is optimistic, though, about the power of franchise owners banding together to force this change. He points to a similar success from 2020, when merchants united to secure the ability to set their own hours and no longer be forced by headquarters to stay open 24 hours.

Dismantling the convenience store accounting system could be next, Kawano says. He already has one small but significant data point supporting this hope: in 2024, 7-Eleven merchants negotiated an ehomaki sushi roll sales goal of just 95% compared to 2023 – marking the first time the target did not exceed the year before. "If we come together, we can make the situation better," Kawano says. "It's like a revolution."

* Rachel Nuwer is a freelance science journalist and author based in New York City. Her reporting in Japan was supported by a grant from the Abe Fellowship Program, administered by the Social Science Research Council and the Japan Foundation New York.

--

If you liked this story, sign up for The Essential List newsletter – a handpicked selection of features, videos and can't-miss news, delivered to your inbox twice a week.