This article's use of external links may not follow Wikipedia's policies or guidelines. (May 2018) |

Xuzhou (Chinese:

Xuzhou

Hsü-chou, Süchow | |

|---|---|

Left to right, top to bottom: Xuzhou skyline, Huaihai campaign Memorial Park, Surabaya Pavilion in Sishuiting Park, Yunlong Lake, the Xuzhou TV Tower | |

| |

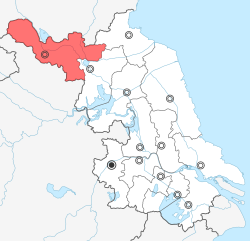

Location of Xuzhou City jurisdiction in Jiangsu | |

| Coordinates (Pengcheng Square): 34°15′54″N 117°11′13″E / 34.265°N 117.187°E | |

| Country | People's Republic of China |

| Province | Jiangsu |

| County-level divisions | 10 |

| Township-level divisions | 161 |

| Municipal seat | Yunlong District |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Zhou Tiegen ( |

| • CPC Committee Secretary | Zhang Guohua (张国华) |

| Area | |

| • Prefecture-level city | 11,259 km2 (4,347 sq mi) |

| • Urban | 3,037 km2 (1,173 sq mi) |

| • Metro | 2,347 km2 (906 sq mi) |

| Population (2020 census)[1] | |

| • Prefecture-level city | 9,083,790 |

| • Density | 810/km2 (2,100/sq mi) |

| • Urban | 3,589,215 |

| • Urban density | 1,200/km2 (3,100/sq mi) |

| • Metro | 3,135,660 |

| • Metro density | 1,300/km2 (3,500/sq mi) |

| GDP[2] | |

| • Prefecture-level city | CN¥ 732 billion US$ 106 billion |

| • Per capita | CN¥ 80,615 US$ 11,683 |

| Time zone | UTC+8 (China Standard) |

| Postal codes | 221000 (Urban center), 221000, 221000, 221000 (Other areas) |

| Area code | 0516 |

| ISO 3166 code | CN-JS-03 |

| Major Nationalities | Han |

| Licence plate prefixes | 苏C |

| Website | Archived link |

| Xuzhou | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

"Xuzhou" in Chinese characters | |||||||||||

| Chinese | |||||||||||

| Postal | Suchow | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Pengcheng | |||||||||||

| Chinese | 彭城 | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

The city is designated as National Famous Historical and Cultural City since 1986 for its relics, especially the terracotta armies, the Mausoleums of the princes and the art of relief of Han dynasty.

Xuzhou is a major city among the top 500 cities in the world by scientific research outputs, as tracked by the Nature Index.[4] The city is also home to China University of Mining and Technology, the only national key university under the Project 211 in Xuzhou and other major public research universities, including Jiangsu Normal University, Xuzhou Medical College, and Xuzhou Institute of Technology.[5]

Romanization

editBefore the official adoption of Hanyu Pinyin, the city's name was typically romanized as Suchow[6] or Süchow,[7][8] though it also appeared as Siu Tcheou [Fou],[9] Hsu-chou,[10] Hsuchow,[11] and Hsü-chow.[8][12]

History

editEarly history

editThe early prehistoric relics around Xuzhou are classified as Dawenkou culture system. Liulin (

During the time of Western Zhou, a Huaiyi chiefdom called Xuyi or Xu rose centered around modern Xuzhou and controlled the Lower Yellow River Valley. Xuyi with its Huaiyi people fought against Zhou and its vassals at irregular intervals. Since its declining, Xuyi once moved the capital to the area of Xuzhou and populated it with people who were migrated southwards.

Pengcheng, named after the ancient Peng state that was centered around Xuzhou, a city at the junction of the ancient Bian and Si Rivers, was founded by Lü (annexed by Song later). Chu took the city in the war of 573 BCE, but ceded the city back to Song in the next year, as a coercive measure.[17]

Imperial China

editIn 208 BC, Xiang Yu and Liu Bang deployed their troops into Pengcheng, where Emperor Yi of Chu later transferred his capital from Xuyi after rebel leader Xiang Liang's death.[18][19] Xiang Yu then exiled the emperor to southern China in 206 BC, the former proclaiming himself as "Hegemon-King of Western Chu", and also establishing his capital in Pengcheng, until 202 BC.

During the Han dynasty, a new Chu Kingdom was established with its capital at Pengcheng. It was ruled by various imperial princes during the Western Han period (202 BC – 9 AD). Liu Jiao, the younger half-brother of Liu Bang, founder of Western Han, became the first Prince of Chu. In 154 BC, the prince Liu Wu participated in the Rebellion of the Seven Princes. However, he was defeated afterwards and Chu's territories were greatly diminished. By the end of the second century, a prosperous Buddhist community had been settled at Pengcheng.[20]

-

Liu Wu's lacquered wood coffin inlaid with jade

-

Liu Wu's jade shroud sewn with gold threads

-

A relief depicting two men gambling

At the turn of the second century, Pengcheng changed hands several times among Cao Cao and his rivals before being annexed to Cao Wei in about 200. In the intervening years, the seat of Xuzhou (Xu province) was transferred from Tancheng to Xiapi, which located in the northwest of Suining. While Pengcheng became the seat later than 220.

With the rebellions of the Five Barbarians, considerable local households migrated to the south, a Liu clan from Pengcheng ascended to the gentry, its most well known descendant is Liu Yu, the Emperor Wu of Liu Song. Pengcheng was taken by the Northern dynasties later. Liu Yu recaptured the lost territory in the north of the Huai River in about 408. Xuzhou was divided into two parts: Beixuzhou (North Xuzhou) and Xuzhou (with Jingkou as its seat) in 411. North Xuzhou whose seat was Pengcheng bounded on the south by the Huai River. Beixuzhou was restored as Xuzhou a decade later, while its south counterpart was renamed Nanxuzhou (South Xuzhou). Since then, Pengcheng remained being the seat of Xuzhou until it was eliminated in the early Ming.

The raging wars inflicted upon Xuzhou until the Emperor Taizong of Tang's enthronement in 626. Keeping the northern rebellions and warfare a distance gave Xuzhou scope for developing during the most period of the Tang dynasty. According to the Old Book of Tang and the New book of Tang, in 639, the total population of Pengcheng County, Fei County and Pei County was only 21,768, versus 205,286 in 742.[21]

In 781, Li Na marched south to besiege Xuzhou. Although his revolt was quell soon, the halt of the transport by the Bian Canal impelled the court to secure the area.[22]

The then prefect of Xuzhou, Zhang Jianfeng was designated as the first military governor of Xuzhou–Sizhou–Haozhou (

Three thousand men surrendered and were sent to the south to join the two thousand former Wuning soldiers there. The breached pledge irritated them. Led by Pang Xun, some soldiers mutinied and marched back north.[27] They have unimpeded access to the area by the winter of 868.[28] The local civil governor refused Pang's demand to have the hatred officers removed, and a military confrontation ensued. Thousands of local peasants joined the rebels. They took the prefectural city of Xuzhou, captured the civil governor, and killed those officers. Pang acquired a considerable following. Still, the rebellion was suppressed a year later eventually. Wuning was renamed Ganhua (

After the Yellow River began to change course during the Song dynasty, heavy silting at the Yellow River estuary forced the river to channel its flow into the lower Huai River tributary. The area became barren thereafter due to persistent flooding, nutrient depletion and salination of the once fertile soil.

In the first month of 1129, Nijuhun took the city after a siege of 27 days, and the then governor Wang Fu (

In 1232, the general Wang You (

A rebellion against Yuan rose by Li Er (

Zhang Shicheng occupied Xuzhou as the northernmost city of his domain in 1360.[38] The Ming forces under Xu Da, captured Xuzhou in 1366.[39] Soon Köke Temür sent an army under General Li Er to attack Xuzhou. Fu Youde (

Xuzhou had a long period of prosperity during the Ming dynasty. The flourishness largely attributed to the carriage, especially by the Grand Canal,[41] one of seven customs barriers (or customs houses, 鈔關) under the Ministry of Revenue was located in Xuzhou.[42] It was retained until the late Qing.[43] Korean Choe Bu affirmed that the city where he travelled by way of, hardly pale by comparison to the Jiangnan region.[44]

As a hub for both the national courier system and the grain tribute system for several centuries, Xuzhou was of vital importance.[45] Thus, the government of Ming established three garrison areas namely guards in the present-day area: Xuzhou guard (

Yet, the local navigation was considerably constrained by two Rapids: the Xuzhou Rapids (

After the Hongguang Emperor enthroned in Nanjing, the court designated four defense areas along the southern bank of the Yellow River (

The seismic activity of the Tancheng earthquake in 1688 was also involved Xuzhou. "More than half the houses of the city were ruined" and "led to enormous deaths", according to the gazetteer.[52]

In the 1850s, the Yellow River shifted its course from the southern to the northern side of the Shandong peninsula, the process caused serious floods and famine in Xuzhou, and almost made the waterway system within the prefecture defunct.

Modern China

editZhang Xun and his remaining army fled to Xuzhou after the Revolution of 1911. They entered the city on 5 December. The Nanking Government sent three armies to attack Xuzhou. In the middle of February 1912, Zhang evacuated the city and moved north after he was defeated.

Since the Second Revolution began, Xuzhou became a front-line city. The Revolutionary Army fared badly as it advanced from there towards the north, and a rout ensued. Then the Beiyang Army captured the city on 24 July. Thereafter, Zhang Xun made Xuzhou his base. he convened four meetings of the Beiyang leadership. Involved the stalemate among Li Yuanhong and Duan Qirui in 1917, he marched on Beijing with a troop in June. His failure spread and caused a terrible wave of theft and arson committed by his garrisons later in Xuzhou in July.

The Zhili clique dominated Xuzhou by 1924. In the autumn of this year, the Second Zhili–Fengtian War broke out, Zhang Zongchang who supported the Fengtian clique seized the city with his thirty thousand soldiers. Sun Chuanfang led a coalition of forces to sortie the Fengtian Army in October 1925. They occupied the city on 8 November. As the leader of the Northern Expedition, Chiang Kai-shek arrived in Xuzhou on 17 June 1927.[53] He conferred with Feng Yuxiang and other Kuomintang officers on 20 June, Feng was courted by Nanjing.[54] Then Sun Chuanfang and Zhang Zongchang began to fight in unison against the Nationalist government. They captured the city on 24 June. The fall of Xuzhou aroused public outrage, Chiang 's first resignation ensued. On 16 December, Nanjing force took the area again.[55]

The area was the main site both of the Battle of Xuzhou in 1938 against the Japanese Army in the Second Sino-Japanese War and of the battle in the Chinese Civil War, the Huaihai Campaign in 1948–49.

On 19 May 1938, Chiang gave the order to abandon Xuzhou, then Japanese military took control of the city.

The Administrative Commission of the Su-Huai Special Region (

After the Second Sino-Japanese War, the troop under He Zhuguo entered Xuzhou on 6 September. The Xuzhou Pacification Commission (

Guo Yingqiu as the representative of the CPC went to Xuzhou to negotiate a regional truce, since 10 February 1946. On 2 March, the "Committee of Three", comprising George Marshall, Zhang Zhizhong and Zhou Enlai arrived for the ceasefire in Central China. Still, the KMT and the CPC came into conflict soon. The CPC revealed that Yasuji Okamura assisted the KMT in the local warfare against the PLA.

The Huaihai was the a critical of the trinity of the major campaigns during the Chinese Civil War. Fighting centred around the city of Xuzhou, seat of the Bandit Suppression Headquarters (剿匪

-

Zhang Xun's troops in Xuzhou, the 1910s

-

Chiang Kai-shek conferred with Feng Yuxiang in Xuzhou, 1927

-

The "Committee of Three" met in Xuzhou, 1946

-

Mao Zedong at the platform of Xuzhou Railway Station in 1953

Then Xuzhou (the old urban area) was made a part of Shandong province temporarily, together with the rest area of the northern Jiangsu along the Longhai Railway. The city was returned to Jiangsu as the province was restored in 1953.

The railways in Xuzhou bore the brunt of the transporting muddle in the 1970s, Beijing was concerned with the issue in 1974. Thus, the then Minister of Railways, Wan Li went to Xuzhou to inspect and rectify in March. It was deemed as a breakthrough on restoring order later.[60]

On April 22, 1993, Xuzhou was ratified as a "Larger Municipality" with legislative power by the State Council.[61]

Administration

editThe evolutionary history

edit| The table of local administrative changes | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Period | Provincial Level | Prefectural Level | County Level | ||||

| Spring and Autumn |

Song (state) |

Pengcheng 彭城 Liuyi Lüyi | |||||

| Zhongwu (state) | |||||||

| Warring States |

Chu (state) |

Peiyi 沛邑 | |||||

| Qi (state) |

Changyi | ||||||

| Pi (state) 邳國 | |||||||

| Qin dynasty | Sishui Commandery |

Pei County 沛縣 Pengcheng County 彭城 Liu County Xiao County | |||||

| Donghai Commandery |

Xiapi County | ||||||

| Western Han | Xu Province |

Chu (state) |

Lü County Wuyuan County | ||||

| Donghai Commandery |

Siwu County Marquis Jianling's state Marquis Liangcheng's state Marquis Rongqiu's state | ||||||

| Yu Province |

Pei Commandery 沛郡 |

Pei County 沛縣 Feng County Guangqi County | |||||

| Eastern Han and Three Kingdoms |

Xu Province |

Pengcheng (state) 彭城 |

Pengcheng County 彭城 Liu County Lü County Wuyuan County Guangqi County | ||||

| Xiapi (state) |

Xiapi County Liangcheng County Siwu County | ||||||

| Yu Province |

Pei (state) 沛國 |

Pei County 沛縣 Feng County | |||||

| Jin dynasty, Northern and Southern dynasties |

(North) Xuzhou or (North) Xu Province ( South Xuzhou or South Xu Province Zhenjiang, see Zhenjiang |

Pengcheng Commandery 彭城 |

Pengcheng County 彭城 Liu County Lü County | ||||

| Xiapi Commandery |

Xiapi County Liangcheng County Siwu County | ||||||

| Pei Commandery 沛郡 |

Pei County 沛縣 Feng County | ||||||

| Jiyin Commandery 济阴 |

Suiling County 睢陵 | ||||||

| Sui dynasty | Pengcheng Commandery 彭城 |

Pengcheng County 彭城 Liu County Pei County 沛縣 Feng County | |||||

| Xiapi Commandery |

Xiapi County Liangcheng County | ||||||

| Tang dynasty | Henan Circuit |

Xuzhou |

Pengcheng County 彭城 Pei County 沛縣 Feng County | ||||

| Sizhou 泗州 | Xiapi County | ||||||

| Northern Song |

West Jingdong Circuit |

Xuzhou |

Pengcheng County 彭城 Pei County 沛縣 Feng County Baofeng Jian* Liguo Jian* | ||||

| East Jingdong Circuit |

Huaiyang Military 淮陽 |

Xiapi County | |||||

| Jin | West Shandong Circuit |

Xuzhou |

Pengcheng County 彭城 Feng County | ||||

| Huaiyang Military 淮陽 |

Xiapi County | ||||||

| Tengzhou 滕州 | Pei County 沛縣 | ||||||

| Yuan dynasty | Henanjiangbei Province |

Gui’de-fu |

Xuzhou |

Xiao County | |||

| Pizhou 邳州 | Xiapi County Suining County 睢寧 | ||||||

| Branch Secretariats |

Jining Circuit |

Jizhou |

Pei County 沛縣 | ||||

| Feng County | |||||||

| Ming dynasty | Nanquin/South Zhil |

Xuzhou (as an Independent Department) |

Pei County 沛縣 Feng County Xiao County Dangshan County 碭山 | ||||

| Huaian-fu 淮安 |

Pizhou 邳州 | ||||||

| Qing dynasty, during 1733–1911 |

Kiangsu/Jiangsu Province |

Xuzhou-fu (as a Prefecture) |

Tongshan County Pei County 沛縣 Feng County Xiao County Dangshan County 碭山 Suining County 睢寧 Suqian County Pizhou 邳州 | ||||

| Republic of China, during 1945–1949 |

Kiangsu/Jiangsu Province |

Xuzhou City | |||||

| No.9 Administrative Superintendent District |

Tongshan County Pei County 沛縣 Feng County Xiao County Dangshan County 碭山 Suining County 睢寧 Pi County 邳縣 | ||||||

| People's Republic of China, during 1949–1952 |

Shandong Province |

Xuzhou City |

Tongshan County 铜山县 | ||||

| Prefecture of Teng County 滕县专区 |

Tongbei County 铜北县 Pei County 沛县 Feng County 丰县 | ||||||

| Prefecture of Linyi 临沂专区 |

Pi County 邳县 | ||||||

| Administrative Region of the Northern Anhui 皖北 |

Prefecture of Su County |

Xiao County 萧县 Dangshan County 砀山县 | |||||

| People's Republic of China, in 1955 |

Jiangsu Province |

Xuzhou City |

Gulou District Yunlong District Zifang District Wangling District Jiawang Mining District 贾汪矿区 | ||||

| Prefecture of Xuzhou |

Xinhailian City Tongshan County 铜山县 Pei County 沛县 Feng County 丰县 Suining County 睢宁县 Pi County 邳县 Xinyi County Donghai County 东海县 Ganyu County 赣榆县 | ||||||

| Anhui Province |

Prefecture of Su County |

Xiao County 萧县 Dangshan County 砀山县 | |||||

| People's Republic of China, in 1963 |

Jiangsu Province |

Xuzhou City |

Gulou District Yunlong District Jiawang Town 贾汪镇 Jiaoqu 郊区(办事处) | ||||

| Prefecture of Xuzhou |

Tongshan County 铜山县 Pei County 沛县 Feng County 丰县 Suining County 睢宁县 Pi County 邳县 Xinyi County Donghai County 东海县 Ganyu County 赣榆县 | ||||||

| People's Republic of China, in 1983 |

Jiangsu Province |

Xuzhou City |

Gulou District Yunlong District Jiaoqu 郊区 Jiawang District 贾汪 Kuangqu 矿区 Tongshan County 铜山县 Pei County 沛县 Feng County 丰县 Suining County 睢宁县 Pi County 邳县 Xinyi County | ||||

| Lianyungang City 连云 |

Donghai County 东海县 Ganyu County 赣榆县 | ||||||

| People's Republic of China, in 1993 |

Jiangsu Province |

Xuzhou City |

Gulou District Yunlong District Quanshan District Jiawang District 贾汪 The Mining District 矿区 Pizhou City 邳州 Xinyi City Tongshan County 铜山县 Pei County 沛县 Feng County 丰县 Suining County 睢宁县 | ||||

| People's Republic of China, 2010–present |

Jiangsu Province |

Xuzhou City |

Gulou District Yunlong District Quanshan District Jiawang District 贾汪 Tongshan District 铜山 Pizhou City 邳州 Xinyi City Pei County 沛县 Feng County 丰县 Suining County 睢宁县 | ||||

The present administrative division

editThe prefecture-level city of Xuzhou administers ten county-level divisions, including five districts, two county-level cities and three counties. These are further divided into 161 township-level divisions, including 63 subdistricts and 98 towns.[62]

| Map | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Chinese | Hanyu Pinyin | Population (2020) | Area (km2) | Density (/km2) |

| City Proper | |||||

| Gulou District | Gǔlóu Qū | 806,550 | 222.6 | 3,623 | |

| Yunlong District | Yúnlóng Qū | 471,566 | 120.0 | 3,930 | |

| Quanshan District | Quánshān Qū | 619,784 | 102.4 | 6,053 | |

| Suburban | |||||

| Jiawang District | 贾汪 |

Jiǎwāng Qū | 453,555 | 612.4 | 740.6 |

| Tongshan District | 铜山 |

Tóngshān Qū | 1,237,760 | 1,952 | 634.1 |

| Rural | |||||

| Feng County | 丰县 | Fēng Xiàn | 935,200 | 1,447 | 646.3 |

| Pei County | 沛县 | Pèi Xiàn | 1,038,337 | 1,328 | 781.9 |

| Suining County | 睢宁县 | Suīníng Xiàn | 1,088,553 | 1,768 | 615.7 |

| Satellite cities (County-level cities) | |||||

| Xinyi City | Xīnyí Shì | 969,922 | 1,573 | 616.6 | |

| Pizhou City | 邳州 |

Pīzhōu Shì | 1,462,563 | 2,086 | 701.1 |

| Total | 9,083,790 | 11,211 | 810.3 | ||

Geography

editXuzhou is of strategic importance for linking South China and North China. The boundaries of its jurisdiction are adjacent to Lianyungang and Suqian in east; Suzhou of Anhui province to the south; Huaibei to the west; Linyi, Zaozhuang, Jining and Heze of Shandong province to the north.

The area can be divided into four sectors from east to west, constitute the Shandong–Jiangsu Traps (鲁苏

The confluence of the former Si River and the former Bian Canal was situated northeast of ancient Xuzhou city. The city and its hinterland were areas liable to severe flooding from the Yellow River since the tenth century. In 1194, the Yellow River changed its course to join the Si River, a former tributary of the Huai. From then on, the Yellow River flowed along the north of the walled city until diverting in 1855. The city proper is now bisected by the ancient Yellow River course, while Yunlong Lake is located in the southwest. North of the lake is Yunlong Park.

Climate

editXuzhou has a monsoon-influenced humid subtropical climate (Köppen Cwa), with cool, dry winters, warm springs, long, hot and humid summers, and crisp autumns. The monthly daily average temperature ranges from 0.7 °C (33.3 °F) in January to 27.3 °C (81.1 °F) in July; the annual mean is 14.9 °C (58.8 °F). Snow may occur during winter, though rarely heavily. Precipitation is light in winter, and a majority of the annual total of 842.8 millimetres (33.2 in) occurs from June thru August. With monthly percent possible sunshine ranging from 44% in July to 54% in three months, the city receives 2,221 hours of bright sunshine annually.

The lowest temperature recorded in Xuzhou was −23.3 °C (−10 °F), on 6 February 1969, while the highest was 43.4 °C (110 °F), on 15 July 1955.[63]

| Climate data for Xuzhou (1991–2020 normals, extremes 1981–2010) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 19.8 (67.6) |

25.9 (78.6) |

30.1 (86.2) |

34.8 (94.6) |

38.2 (100.8) |

40.6 (105.1) |

43.4 (110.1) |

38.2 (100.8) |

36.2 (97.2) |

34.5 (94.1) |

29.0 (84.2) |

21.3 (70.3) |

43.4 (110.1) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 5.6 (42.1) |

9.1 (48.4) |

14.8 (58.6) |

21.4 (70.5) |

26.7 (80.1) |

30.7 (87.3) |

31.8 (89.2) |

30.8 (87.4) |

27.2 (81.0) |

21.9 (71.4) |

14.4 (57.9) |

7.7 (45.9) |

20.2 (68.3) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 1.0 (33.8) |

4.1 (39.4) |

9.5 (49.1) |

16.0 (60.8) |

21.5 (70.7) |

25.8 (78.4) |

27.7 (81.9) |

26.8 (80.2) |

22.5 (72.5) |

16.5 (61.7) |

9.2 (48.6) |

2.9 (37.2) |

15.3 (59.5) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | −2.6 (27.3) |

0.1 (32.2) |

4.8 (40.6) |

10.8 (51.4) |

16.4 (61.5) |

21.2 (70.2) |

24.3 (75.7) |

23.5 (74.3) |

18.5 (65.3) |

12.0 (53.6) |

5.0 (41.0) |

−0.8 (30.6) |

11.1 (52.0) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −17.3 (0.9) |

−23.3 (−9.9) |

−7.6 (18.3) |

−1.4 (29.5) |

4.8 (40.6) |

12.4 (54.3) |

15.9 (60.6) |

13.4 (56.1) |

5.0 (41.0) |

−1.0 (30.2) |

−8.3 (17.1) |

−13.5 (7.7) |

−23.3 (−9.9) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 18.4 (0.72) |

20.9 (0.82) |

32.3 (1.27) |

36.8 (1.45) |

64.3 (2.53) |

118.4 (4.66) |

238.3 (9.38) |

152.6 (6.01) |

70.3 (2.77) |

38.5 (1.52) |

35.6 (1.40) |

19.1 (0.75) |

845.5 (33.28) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.1 mm) | 4.3 | 4.9 | 5.7 | 6.7 | 6.7 | 7.4 | 12.8 | 11.2 | 7.4 | 5.7 | 5.9 | 4.2 | 82.9 |

| Average snowy days | 3.4 | 2.6 | 1.1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.6 | 1.9 | 9.6 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 66 | 63 | 60 | 61 | 63 | 65 | 78 | 80 | 74 | 69 | 70 | 67 | 68 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 137.3 | 145.9 | 189.8 | 215.1 | 227.0 | 203.4 | 182.4 | 181.2 | 178.2 | 179.4 | 152.6 | 145.7 | 2,138 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 44 | 47 | 51 | 55 | 53 | 47 | 42 | 44 | 48 | 52 | 49 | 48 | 48 |

| Source: China Meteorological Administration[64][65][66] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

editAccording to the 1% National Population Sample Survey in 2015, the total resident population of Xuzhou reached 8.66 million, and the sex ratio was 101.40 males to 100 females.[67]

| Year | Urban areas | Tongshan | Feng | Pei | Suining | Pizhou | Xinyi | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1913 | 826,083 | 291,562 | 280,345 | 501,867 | 636,040 | 2,535,897 | ||

| 1918 | 854,213 | 281,696 | 294,604 | 506,975 | 639,064 | 2,576,552 | ||

| 1928 | 954,939 | 308,968 | 329,933 | 508,226 | 568,193 | 2,670,259 | ||

| 1932 | 986,536 | 304,480 | 346,593 | 547,848 | 584,904 | 2,770,361 | ||

| 1935 | 1,099,296 | 364,007 | 391,121 | 645,890 | 642,641 | 3,142,955 | ||

| 1953 | 333,190 | 1,072,430 | 473,815 | 395,094 | 653,854 | 683,113 | 452,203 | 4,063,699 |

| 1964 | 505,417 | 1,001,377 | 587,822 | 575,237 | 729,619 | 861,117 | 518,086 | 4,778,675 |

| 1982 | 779,289 | 1,414,460 | 834,568 | 869,778 | 981,917 | 1,187,526 | 741,600 | 6,809,138 |

| 1990 | 949,267 | 1,741,522 | 952,760 | 1,042,280 | 1,160,772 | 1,431,728 | 883,650 | 8,161,979 |

| 2002 | 1679626 | 1,262,489 | 1,068,404 | 1,183,048 | 1,217,820 | 1,539,922 | 962,656 | 8,913,965 |

| 2010 | 1,911,585 | 1,142,193 | 963,597 | 1,141,935 | 1,042,544 | 1,458,036 | 920,610 | 8,580,500 |

Economy

editHistorically, Xuzhou and the surrounding regions were a predominantly agricultural area. Its arable land was severely depleted by the changes in the course of the Yellow River since the mid 11th century, and the drought-resistant crops: wheat, sorghum, soybean, maize and potato, became the local staples. Besides, cotton, peanut, tobacco and sesame also grew in low-yield. The local mining traces it origins to an iron mine, Liguo. It was exploited since Han dynasty, and managed by a particular bureau in Song. And the city had major coal reserves of the province.[68] Local coaling began by the 1070s, according to a lyric of the then governor Su Shi.[69] Copper smelting in this area supposedly started in the Three Kingdoms era.[70]

The city astride the old course of the Grand Canal had been through several transitory periods of prosperity, before the grain tribute system was abolished in 1855. It remained being economically backward in the 1940s for wars, and a few people engaged in industrial sectors.

Later the CPC positioned the city as a region of coal mining and heavy industry. Its dominant sectors are machinery, energy and food production nowadays. The construction machinery manufacturer XCMG is the largest company based in Xuzhou. It was the world's tenth-largest construction equipment maker measured by 2011 revenues, and the third-largest based in China (after Sany and Zoomlion).[71]

Education

edit

Xuzhou was a regional centre for education, but two defunct institutions once chose their sites within the city: Provincial College of Kiangsu (

Schools

edit- Xuzhou No.1 Middle School (

徐 州 市 第 一 中学 ) - Xuzhou No.2 Middle School (

徐 州 市 第 二 中学 ) - Xuzhou No.3 Middle School (

徐 州 市 第 三 中学 ) - Xuzhou Senior High School (

徐 州 市 高 级中学 ) - Xuzhou No.5 Middle School

- Xuzhou No.36 Middle School (

徐 州 市 第 三 十 六 中学 ) - Xuzhou No.13 Middle School (

徐 州 市 第 十 三 中学 )

Universities and colleges

edit- China University of Mining and Technology (

中国 矿业大学 ) - Jiangsu Normal University (

江 苏师范大学 ) - Xuzhou Medical University (

徐 州 医科 大学 ) - Xuzhou Institute of Technology (

徐 州 工程 学院 暨徐州 大学 ) - People's Liberation Army Air Force Logistical College (

中国 人民 解放 军空军后勤学 院 )

Religion

editAccording to the local administrator's survey in 2014, around 4.76% of the population of Xuzhou, namely 0.46 million people belongs to organised religions. The largest groups being Protestants with 350,000 people, followed by Buddhists with 70,000 people.

Xuzhou is deemed one of earlier Buddhist centres in China supposedly because the Emperor Ming of Han mentioned that the then Prince of Chu Liu Ying built a "temple for Buddha".[72]

The local Catholic activities were dominated by the French-Canadians of the Society of Jesus since the 1880s,[73] and there were 73,932 adherents and seventeen churches in 1940. Cathedral of the Sacred Heart of Jesus, completed in 1910, is still a principal church nowadays. While the initial Protestant mission in Xuzhou was led by Alfred G. Jones of BMS, then American Southern Presbyterian Mission took over it in the 1890s.

Culture

editArts

editAccording to Xu Wei's Nanci Xulu (

The new municipal concert hall was opened in 2011, shaped like a myrtle flower. However, the various regular performances are unattainable. While the first local philharmonic orchestra is established in 2015.

Media

editThe first local newspaper entitled Hsing-hsü Daily (醒徐

| Station | Chinese name | Frequency |

|---|---|---|

| News Radio | 93.0 FM | |

| Private Motor Radio | 91.6 FM | |

| Traffic Radio | 103.3 FM | |

| Joy Radio | 89.6 FM |

| Channel | Chinese name | Description |

|---|---|---|

| XZ·1 | News & General | |

| XZ·2 | Economy & Life | |

| XZ·3 | Arts & Entertainment | |

| XZ·4 | Public |

The earliest local radio was broadcasting in 1934 for public education. Then Japanese military founded Hsuchow Broadcasting Station (

Museums

editDialect

editAs a subdialect of Central Plains Mandarin, Xuzhou dialect is spoken in the whole area, especially in the suburb and countryside.

Cuisine

editXuzhou cuisine is closely related to Shandong cuisine's Jinan-style. Xuzhou's most well known foods include bǎzi ròu (pork belly, and other items stewed in a thick broth), sha tang ( 汤), and various dog meat dishes.

Another one of Xuzhou's famous dishes is dì guō (

Fu Yang Festival(

Transport system

editRoads

editXuzhou has many urban expressways: Xuzhou 3rd Ring Road expressways (east, north and west), Xuzhou East Ave. expressway (

Xuzhou is the sixth city which has a fifth Ring Road (

Expressways

edit- G2 Beijing–Shanghai Expressway

- G2513 Huai'an–Xuzhou Expressway

- G3 Beijing–Taipei Expressway

- G30 Lianyungang–Khorgas Expressway

- S49 Xinyi–Yangzhou Expressway

- S65 Xuzhou–Mingguang Expressway

- S69 Jinan–Xuzhou Expressway

National Highways

edit- China National Highway 104

- China National Highway 205

- China National Highway 206

- China National Highway 311

Rail

editXuzhou is an important railway hub, where two major passenger stations: Xuzhou Railway Station and Xuzhou East Railway Station (Xuzhoudong Railway Station) are situated in. Xuzhou Railway Station is at the intersection of Jinghu Railway and Longhai Railway. While Xuzhou East Railway Station on the eastern outskirts is the junction of the Beijing–Shanghai and Xuzhou–Lanzhou high-speed railways. Xuzhou is the only city which has three huge railway stations (Xuzhou Railway Station, Xuzhoudong Railway Station and Xuzhoubei Railway Station) in Jiangsu Province.

Aviation

editXuzhou Guanyin International Airport is one of the three biggest international airports in Jiangsu Province, it serves the area with scheduled passenger flights to major airports in China. Xuzhou Guanyin International Airport (

Xuzhou Metro System

editXuzhou Metro is the first subway in North Jiangsu. The project was approved by State Council in 2013. Three subway lines are being built and expected to be completed by 2019-2021 one after another, with total length of 67 km and 3 transfer stations: Pengcheng Square Station (Change for Metro Line 1 and Line 2), Xuzhou Railway Station (Change for Metro Line 1 and Line 3) and Huaita Station (Change for Metro Line 2 and Line 3).

Metro Line 1 (Xuzhoudong Railway Station - Luwo Station via Xuzhou Railway Station and Pengcheng Square Station) (

Metro Line 2 (Keyunbei Station - Xinchengqudong Station via Pengcheng Square Station and Jiangsu Normal University Yunlong Campus) (

Metro Line 3 (Xiadian Station - Gaoxinqu’nan Station via Xuzhou Railway Station and China University of Mining and Technology Wenchang Campus and Jiangsu Normal University Quanshan Campus)(

Metro Line 4 (Qiaoshangcun Station - Tuolanshan Road Station), the construction started on July 27, 2022. Xuzhou Metro Line 4 has a total length of 26.2 km, with an average station spacing of 1.456 km, all of which are underground lines. The project has 19 underground stations, including 8 transfer stations.

Metro Line 5 (Olympic Center South Station - Xukuangcheng Station). Xuzhou Metro Line 5 is expected to start construction in 2023. The total length of the line is about 24.9 km, with 20 stations, including 7 transfer stations, all of which are underground lines, with an average distance of 1.28 km.

Metro Line 6 (Xuzhoudong Railway Station - Tongshan Chinese Medical Hospital Station), the construction started on November 28, 2020. Xuzhou Metro Line 6 has a total length of 22.912 km, with an average station spacing of 1.496 km, a maximum station spacing of 3.072 km and a minimum station spacing of 0.809 km, all of which are underground lines. The project has a total of 16 underground stations, including 6 transfer stations.

According to Xuzhou Metro Group, the Xuzhou Metro Line 3 (Phase 2), Line 4, Line 5 and Line 6 will be finished construction before 2026.[75] In the future, Xuzhou Metro System will include at least 11 Subway lines: Xuzhou Metro Line 7, Xuzhou Metro Line S1, Xuzhou Metro Line S2, Xuzhou Metro Line S3, Xuzhou Metro Line S4, Xuzhou Metro Line S5, Xuzhou Metro Line 1 (Phase 2), Xuzhou Metro Line 2 (Phase 2), Xuzhou Metro Line 5 & 6 (Phase 2 & 3) etc.

Others

editThe Grand Canal flows through Xuzhou, and the navigation route extends from Jining to Hangzhou.

Luning oil pipeline, which originates from Linyi county of Shandong to Nanjing, passes through Xuzhou.

Military

editXuzhou is headquarters of the 12th Group Army of the People's Liberation Army, one of the three group armies that compose the Nanjing Military Region responsible for the defense of China's eastern coast and possible military engagement with Taiwan. The People's Liberation Army Navy also has a Type 054A frigate that shares the name of the region.

See also

editCitations

edit- ^ "China: Jiāngsū (Prefectures, Cities, Districts and Counties) - Population Statistics, Charts and Map".

- ^ "

存 档副本 ". Archived from the original on 2019-10-07. Retrieved 2019-10-07. - ^

国 务院关于徐 州 市城 市 总体规划的 批复(国 函 〔2017〕78号 )_政府 信 息 公 开专栏. www.gov.cn. Archived from the original on 2017-08-25. Retrieved 2018-01-15. - ^ "Nature Index 2018 Science Cities | Nature Index Supplements | Nature Index". www.natureindex.com. Retrieved 2020-11-26.

- ^ "US News Best Global Universities Rankings in Xuzhou". U.S. News & World Report. 2021-10-26. Retrieved 2021-10-26.

- ^ Postal romanization, See, e.g., this 1947 ROC map.

- ^ Rosario Renaud, Süchow. Diocèse de Chine 1882-1931, Montréal, 1955.

- ^ a b Canadian Missionaries, Indigenous Peoples: Representing Religion at Home and Abroad. University of Toronto Press. 2005. p. 208. ISBN 9780802037848.

- ^ Louis Hermand, Les étapes de la Mission du Kiang-nan 1842-1922 et de la Mission de Nanking 1922-1932, Shanghai, 1933.

- ^ See: Wade-Giles.

- ^ Jaques, Tony (2007). Dictionary of Battles and Sieges: P-Z. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 1116. ISBN 978-0-313-33539-6. Archived from the original on 2016-11-26. Retrieved 2018-02-05.

- ^ Twitchett, Fairbank (2009). The Cambridge History of China, Vol. 5: The Sung Dynasty and Its Precursors, 960-1279 AD, Part I. Cambridge University Press. p. 1042. ISBN 978-0521812481.

- ^

江 苏邳州 梁 王城 遗址大 汶口文化 遗存发掘简报 [Brief Excavation Report of the Remains of Dawenkou Culture at the Site of Liangwangcheng in Pizhou, Jiangsu] (PDF). Southeast Culture 东南文化 . 2013 (4): 21–41. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-09-04. Retrieved 2017-04-29. - ^ Yu, Weichao.

銅山 丘 湾 商 代 社 祀 遗迹的 推定 .考古 (Archaeology). 1973 (5): 296–298. - ^

竹 書 紀年 [Bamboo Annals].武 丁 …四 十 三 年 ,王師 滅 大 彭 - ^

國語 Guoyu [Discourses of the States].彭、

豕 韋為商 伯 矣。當 週 未 有 …彭姓彭祖、豕 韋、諸 稽,則 商 滅 之 矣 - ^ Ji (2008), p. 8.

- ^ Ji (2008), p. 17.

- ^ Twitchett, Loewe (1987), p. 114.

- ^ Twitchett, Loewe (1987), p. 670.

- ^ a b Jiangsu Provincial Chorographies: Demography Chorography (in Simplified Chinese). Nanjing: Jiangsu Guji Press. 1999. ISBN 7-80122-5260.

- ^ Twitchett (2007), p. 593.

- ^ Twitchett (2007), p. 541.

- ^ Twitchett (2007), p. 687, 697.

- ^ Twitchett (2007), p. 516, 557.

- ^ Twitchett (2007), p. 558, 697.

- ^ Twitchett (2007), p. 696.

- ^ Twitchett (2007), p. 697.

- ^ Twitchett (2007), p. 727.

- ^ History of Song. 25. "

三 年 春 正月 ...丙午 ,粘 罕陷徐 州 ,守 臣 王 復 及子倚死之 ,軍 校 趙 立 結 鄉 兵 為 興 復 計 ...金 兵 執 淮陽守 臣 李 寬 ,殺 轉 運 副使 李 跋 ,以騎兵 三 千 取 彭城,間道 趣 淮甸", "三 月 ...趙 立 復 徐 州 "; 448. "建 炎 三 年 ,金 人 攻 徐 ,王 復 拒 守 …城 始 破 ,立 巷 戰 …陰 結 鄉 民 為 收 復 計 。金 人 北 還 ,立 率 殘 兵 邀擊 ,斷 其歸路 ,奪 舟 船 金 帛以千 計 ,軍 聲 複 振 。乃盡結 鄉 民 為 兵 ,遂 複 徐 州 "; Study of Northern Alliances During the Three Reigns [三朝 北 盟 會 編 ]. 134. "趙 立方 知 徐 州 ,以徐州 城 孤 且乏糧 不可 守 ,乃率将兵 及民兵 約 三 萬 趨行在 " - ^ a b

金 史 ·列 传第五 十 五 . Archived from the original on 2016-12-03. - ^

金 史 ·列 传第五 十 一 . Archived from the original on 2016-12-03. - ^

元 史 ·列 传第三 十 七 . Archived from the original on 2016-12-20. - ^

元 史 ·列 传第三 十 五 . Archived from the original on 2016-12-20. - ^ History of Yuan. 42. "

八 月 ...丙 戌 ,蕭 縣 李 二及 老 彭、趙 君 用 攻 陷 徐 州 。李 二 號 芝 麻 李 ,與 其黨亦 以燒香 聚眾而反", "二 月 ...戊子 ,詔 :「徐 州 內外群聚 之 眾,限 二 十 日 ,不 分 首 從 ,並 與 赦原」", "秋 七 月 ...以征西 元帥 斡羅為 章 佩添設 少 監 ,討徐州 。脫 脫 請親出師 討徐州 ,詔 許 之 ", "八 月 ...辛 卯 ,脫 脫 復 徐 州 ,屠 其城,芝 麻 李 等 遁走 "; 138. "十 二 年 ,紅 巾 有 號 芝 麻 李 者 ,據 徐 州 。脫 脫 請自行 討之,以逯魯曾為 淮南 宣 慰使,募 鹽 丁 及城邑趫捷,通 二 萬 人 ,與 所 統 兵 俱發。九月 ,師 次 徐 州 ,攻 其西門 。賊 出 戰 ,以鐵翎箭射 馬首 ,脫 脫 不為 動 ,麾軍奮擊之 ,大破 其衆,入 其外郛。明日 ,大兵 四 集 ,亟攻之 ,賊 不能 支 ,城 破 ,芝 麻 李 遁去。獲 其黃繖旗鼓 ,燒 其積聚,追 擒 其偽千 戶 數 十 人 ,遂 屠 其城". - ^ Franke, Twitchett (2006). The Cambridge History of China, Vol. 6: Alien regimes and border states, 907-1368. Cambridge University Press. p. 577. ISBN 978-0-521-24331-5.

- ^ History of Yuan. Vol. 138.

詔 改 徐 州 為 武安 州 ,而立 碑 以著其績 - ^ History of Ming. Vol. 123.

當 是 時 ,士 誠 所 據 ,南 抵紹興 ,北 逾徐州 - ^ History of Ming. Vol. 1.

二 十 六 年 春 ...濠 、徐 、宿 三 州 相 繼 下 - ^

明太 祖 實錄 [Veritable Records of the Hongwu Reign]. Vol. 22.元 將 擴廓帖 木 兒 遣 左 丞 李 二 侵 徐 州 ,兵 駐 陵子 村 。參政 陸 聚令指揮 傅 友 德 禦之,友 德 率 兵 二 千餘泛舟至呂梁,伺其出 掠 ,即 舍 舟 登 入 擊 之 。李 二遣禆將韓乙盛兵迎戰,友 德 奮槊刺 韓 乙 墜馬,其兵敗 去 。友 德 度 李 二必益兵來鬥,趨還城 開門 ,出兵 陳 城 外 ,令 士 皆 臥 槍 以待。有 頃 ,李 二 果 率 眾至,友 德 令 鳴 鼓 ,我 師 奮起 ,沖 其前鋒 。李 二 眾大潰 ,多 溺死 ,遂 生 擒 李 二 及其將士 二 百 七 十 餘人 ,獲 馬 五 百 餘 疋。 - ^ Twitchett, Mote (1998), p. 598.

- ^ Twitchett, Mote (1998), p. 603.

- ^ Peterson (2002). The Cambridge History of China, Vol. 9: The Ch'ing Empire to 1800, Part I. Cambridge University Press. p. 647. ISBN 0-521-24334-3.

- ^

錦 南 漂海錄 [A Record of Drifting Across the Southern Brocade Sea]. Vol. 3.江 以北 ,若 揚 州 、淮安,及淮河 以北 ,若 徐 州 、濟 寧 、臨清,繁華 豐 阜,無 異 江南 ,臨清為 尤 盛 - ^ Twitchett, Mote (1998), p. 590.

- ^ Twitchett, Mote (1998), p. 599.

- ^ Shen, Defu.

萬 曆 野 獲 編 [Unofficial Gleanings from the Wanli Era]. Vol. 12.徐 州 卑濕,自 堤上 視 之 ,如居釜 底 ,與 汴梁相似 ;而堤之 堅 厚 重 復 ,十不得汴二三餘見彼中故老,皆 云 目 中 已 三見 漂溺。須急徒 城 於高阜,如雲龍 、子房 等 山 ,皆 善地 可 版 築 ,不 然 終 有 其魚之 歎。又 城下 洪 河 ,為 古今 孔 道 ,自 通 泇後,軍民 二 運 ,俱不復 經 。商 賈散徒 ,井 邑蕭條 ,全 不 似 一 都會 - ^ For instances, in 1453, see History of Ming. 177. "

景 泰 ...四 年 ...先 是 ,鳳 陽 、淮安、徐 州 大水 ,道 堇相望 ...至 是 山東 、河南 饑 民 就食者 坌至,廩不能 給 。惟 徐 州 廣 運 倉 有余 積 ..."; in 1465, see History of Ming. 161. "夏 寅 ...成 化 元年 考 滿 入 都 ,上 言 :「徐 州 旱 澇,民 不 聊生...」"; in 1518, see江南 通 志 [General Gazetteer of Jiangnan]. 83. "正德 ...十 三年淮徐等處歲饑,截漕運 粟 數 萬石并益以倉儲賑濟"; in 1544, see明世 宗 實錄 [Veritable Records of the Jiajin Reign]. 290. "嘉 靖 二 十 三 年 九 月 …以鳳陽 、淮安、揚 州 、廬 州 並 徐 州 灾傷重大 ,命 正 兌米俱准折 色 "; in 1576, see History of Ming. 84. "萬 曆 ...四 年 ...未 幾 ,河 決 韋家樓 ,又 決 沛縣縷水堤 ,豐 、曹二 縣 長堤 ,豐 、沛、徐 州 、睢甯、金 鄉 、魚 臺 、單 、曹田廬 漂溺無 算 " - ^ History of Ming. Vol. 84.

天啟 ...四 年 六 月 ,決 徐 州 魁 山 堤 ,東北 灌州城 ,城中 水深 一 丈 三 尺 - ^ Mote, Twitchett (2007), p. 633.

- ^ Mote, Twitchett (2007), p. 656.

- ^

江 苏省志 ·地震 事 业志 [Jiangsu Provincial Gazetteer, Volume on Seismic Project] (PDF).江 苏古籍 出版 社 . 1994. pp. 78–9. ISBN 7-80519-550-1. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2018-10-02. Retrieved 2018-10-02. - ^ Fairbank (2005), p. 651.

- ^ Fairbank (2005), p. 665.

- ^ Fairbank (2005), p. 700.

- ^ Jiangsu Provincial Chorographies: Civil Administration Chorography. Beijing: China Local Records Publishing. 2002.

- ^

徐 州 绥靖公 署 军事法 庭 审判日本 战犯回 顾(in Chinese). Archived from the original on 2016-12-26. - ^

不能 忘却 的 审判 (in Chinese (China)). Archived from the original on 2016-12-26. - ^ "Battle of Suchow". Life Magazine, December 6, 1948.

- ^

万里 同志 与 1975年 铁路整 顿. China Railway (in Chinese). Archived from the original on 2018-01-26. Retrieved 2018-01-26. - ^

国 务院关于同意 苏州市 和 徐 州 市 为"较大的 市 "的 批复. Archived from the original on 2016-11-26. - ^

徐 州 市区 划简册 (2016). Archived from the original on 2016-12-21. - ^ 沂沭泗

流域 介 绍 (in Chinese (China)). Archived from the original on 2013-09-16. - ^

中国 气象数 据 网 – WeatherBk Data (in Simplified Chinese). China Meteorological Administration. Retrieved 25 June 2023. - ^

"Experience Template"

中国 气象数 据 网 (in Simplified Chinese). China Meteorological Administration. Retrieved 25 June 2023. - ^

中国 地面 国 际交换站气候标准值月值数据 集 (1971-2000年 ). China Meteorological Administration. Archived from the original on 2013-09-21. Retrieved 2010-05-25. - ^ "The bulletin of 1% National Population Sample Survey in Xuzhou 2015 's main data". Archived from the original on 2016-11-24.

- ^ "Jiangsu Provincial Geography" (in Chinese). Beijing: Beijing Normal University Publishing Group. 2011. ISBN 9787303131686.

- ^ Feng, Yingliu (2001).

石炭 .蘇 軾詩詞 合 注 [Commentary to an Integrator of Several Versions of the Collection of Su Shi's Poetry and Lyrics]. Shanghai. p. 878. ISBN 9787532526529.彭城

舊 無 石炭 。元 豐 元年 十 二 月 ,始 遣 人 訪 獲 於州之 西南 白土 鎮之北 ,冶鐵作 兵 {{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ A triangle-edge copper mirror with carved divine beasts unearthed at the Kurozuka Kofun (

黒 塚 古墳 ), Tenri, Japan, bore "銅 出 徐 州 ;師 出 洛陽 [Copper from Xuzhou; craftsman from Luoyang]". - ^ "Analysis: China's budding Caterpillars break new ground overseas". Reuters. 8 March 2012. Archived from the original on 8 March 2012. Retrieved 8 March 2012.

- ^ History of the Later Han. Vol. 42.

詔 報 曰:「楚 王 誦黃老 之 微 言 ,尚 浮屠 之 仁 祠 ,絜齋三 月 ,與 神 為 誓 ,何 嫌 何 疑 ,當 有 悔吝?其還贖,以助伊 蒲 塞 桑門 之 盛 饌。」 - ^ "Le financement canadien-français de la mission chinoise des Jésuites au Xuzhou de 1931 à 1949" (PDF) (in French).

- ^ "Jiangsu Provincial Chorographies: Press Chorography" (in Chinese). Nanjing:Jiangsu Guji Press.

- ^

徐 州 地 铁1号 线一 期 9月 28日 10:00正式 开通. 2019-09-26. Archived from the original on 2019-09-26. Retrieved 2019-09-28.

General references

edit- Ji, Shijia (2008).

江 苏省志 ・大事 记(上 ) [Provincial Gazetteer of Jiangsu, Volume on Chronology, Part I: Prior to 1912] (PDF). Jiangsu Guji Press. ISBN 978-7-806-43321-8. - Shan, Ma, Shumo, Xiangyong (1999).

江 苏省志 ·地理 志 [Provincial Gazetteer of Jiangsu, Volume on Geography] (PDF). Jiangsu Guji Press. ISBN 978-7-806-43266-2.{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Twitchett, Loewe, Denis, Michael (1987). The Cambridge History of China, Volume 1: The Ch'in and Han Empires, 221 BC–AD 220. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-24327-8.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Twitchett, Denis (2007). The Cambridge History of China, Volume 3: Sui and T'ang China, 589–906, Part 1. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-21446-9.

- Mote, Twitchett, Frederick W., Denis (2007). The Cambridge History of China, Vol. 7: The Ming Dynasty, 1368-1644, Part 1. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-24332-2.

- Twitchett, Mote, Denis, Frederick W. (1998). The Cambridge History of China, Volume 8: The Ming Dynasty, 1368–1644, Part 2. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-24333-9.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Fairbank (2005). The Cambridge History of China, Vol. 9: Republican China 1912-1949, Part 1. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-23541-9.

- Zhao, Liangyu (2015). 环境·经济·

社会 ——近代 徐 州 城市 社会 变迁的 研究 (1882–1948). China Social Sciences Press. ISBN 978-7-516-16418-1.

External links

edit- Government website of Xuzhou (in Simplified Chinese)

- Xuzhou city guide with open directory (Jiangsu.net)