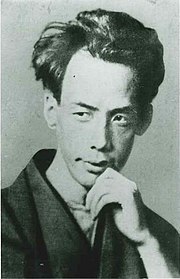

Kan Kikuchi

Kan Kikuchi | |

|---|---|

| |

| Native name | |

| Born | Hiroshi Kikuchi December 26, 1888 Takamatsu, Kagawa |

| Died | March 6, 1948 (aged 59) |

| Occupation | Novelist |

| Nationality | Japanese |

Hiroshi Kikuchi (

Early life and career

[edit]Kikuchi was born on December 26, 1888, in Takamatsu, Kagawa Prefecture, Japan.

In 1904–1905 after the Russo-Japanese War, literature in Japan grew more modern.[2] French Realism was one of the first influences that immersed into Japan's literature. Building from the famous and classic works from the West, which include diaries and autobiographies, Japanese writers formulated a style of fictional writing that is eventually called shinkyo-shosetsu. Other major influences from Western countries in Europe in addition to works from India and China contributed to the creation of modern literature in Japan. In comparison to literature in European countries, new Japanese literature did not achieve as much popularity; few works of Japanese playwrights were translated into European languages.[3] Kikuchi Kan saw the language barrier and inaccuracy of translation as part of the central cause for this.[3]

Irish Influences

[edit]In 1924, shortly after Kaoru Osanai opened Tsukiji Little Theatre, Kikuchi Kan was the most celebrated playwright in Japan. Kan was widely claimed as "a playwright who transformed Irish plays into a Japanese context," including John Millington Synge's Deirdre of the Sorrows. When studying at the University of Kyoto, Kikuchi Kan had a great interest in modern drama, particularly Irish modern drama. Dramatists Kan studied included J.M. Synge and Edward Plunkett, 18th Baron of Dunsany.

After graduating from the University of Kyoto, Kan wrote detailed articles on Synge and Irish plays for Teikoku-Bungaku (

Writing Style

[edit]Though Kikuchi Kan recognized distinct characteristics between Western and Japanese cultures, he used his Japanese roots as the foundation of many of his works. This, in turn, resulted in Kikuchi Kan creating his style of writing in Japanese drama.[5] One of his early works, Kayano Yane (

Elements of drama Kikuchi Kan considered to be the most effective are the one-act play and the use of a minimal number of characters. "The one-act play" he wrote, "is different from long plays – three-acts or five-acts. It should extract the most dramatic elements from all and has to effectively treat it within a limited time." With this short amount of time, Kikuchi Kan's portrays his message in a core event with meticulous use of exposition. One important element in his perspective is knowing the difference between writing stories as opposed to writing plays. In that limited time, the play must have the power to "physically bind the audience to the theatre seat," as opposed to stories that "the reader can put into his pocket."[8] From 1914 to 1924, Kan wrote one-act plays for the leading coterie magazine at that time, New Tides of Thought (Shinshichō). New Tides of Thought magazine also contributed to the popularity of Taishō drama.[9] In Kan's one-act plays, he focused on a single dramatic event and had the characters' actions revolve around that event to produce the most tension and most "dramatic force," for one-act plays "should extract the most dramatic elements...within a limited time."[8]

Father Returns

[edit]

One of his most famous works, Chichi Kaeru (Father Returns), is a one-act play that mainly portrays the struggles of a father-son relationship. Father Returns opened in 1920, after being published in the journal New Tides of Thought in 1917.[10] The story revolves around a conflict between a father and son. The eldest son, Ken'ichirō, despises his father, Sōtarō, for his cruel treatment of the family and for deserting them. As the play progresses, the audience learns that Ken'ichirō's hatred towards his father fueled his determination of surpassing his father by providing better support for his family in his absence. After Sōtarō returns one night, the family welcomes him but Ken'ichirō's confrontation with him ultimately drives Sōtarō to leave. The play concludes with Ken'ichirō's sudden change of heart towards Sōtarō and accepting him into the family. After Shinjirō, a younger brother, goes to bring Sōtarō back, the curtain closes before Sōtarō is found. The ending drove Takeda and Ennosuke to alter it to avoid ambiguity, but was changed back to the original to preserve the main message of the play.[11]

Madame Pearl

[edit]Shinju fujin (

Suzuki further argues that many audience members believed that Ruriko was inspired by Yanagihara Byakuren

Naoki and Akutagawa Prizes

[edit]

Kikuchi Kan dedicated the Akutagawa Prize to Ryūnosuke Akutagawa (

The Naoki Prize was created by Kikuchi Kan as tribute to literary author Sanjugo Naoki (

The process of choosing recipients of the two prizes is for the committees to select already published manuscripts in Coterie and commercial magazines and newspapers. After producing the two prizes, Kikuchi Kan initially decided on having the prizes reflect the Kenshō shōsetsu type of award, in which submitted and unpublished manuscripts were selected by a committee. In brief, the Kenshō shōsetsu, the "prize-winning novels" are selected pieces of fiction novels published in newspapers and magazines that received considerable amounts of praise.[19] The Akutagawa Prize committee in 1934 consisted of the members: Bungei Shunjusha, Yamamoto Yuzu, Haruo Satō, Jun'ichirō Tanizaki, Murō Saisei, Kōsaku Takii, Riichi Yokomitsu and Yasunari Kawabata. Kikuchi Kan, Masao Kume and Masajirō Kojima were in both Akutagawa and Naoki Prize Committees.[20]

Kikuchi Kan Prize

[edit]In 1938, the Kikuchi Kan Prize (

Later years

[edit]In 1938, Kikuchi joined the Pen butai (lit. "Pen corps"), a government organisation which consisted of authors who travelled the front during the Second Sino-Japanese War to write favourably of Japan's war efforts in China,[22][23] and became head of the group's navy branch.[24] He was later affiliated with the Nihon bungaku hōkokukai ("Patriotic Association for Japanese Literature"),[25] a subordinate of the Cabinet Intelligence Bureau.[22][26] After the war, he was purged from public service positions as a wartime collaborator.[27]

Selected work

[edit]Kan Kikuchi's published writings encompass 512 works in 683 publications in 7 languages and 2,341 library holdings.[28]

- Okujō no Kyōjin (

屋上 の狂人 ) – The Housetop Madman - Chichi Kaeru (

父 帰 る) – The Father returns - Mumei Sakka no Nikki (

無名 作家 の日記 ) -Anonymous Writer’s Diary - Onshū no Kanata ni (

恩讐 の彼方 に) or Beyond the Pale of Vengeance - Tadanaokyō Gyōjōki (

忠直 卿 行状 記 ) - Rangaku Kotohajime (

蘭学 事始 ) [1] - Tōjūrō no Koi (

藤 十郎 の恋 ) – Tōjūrō's love- film adaptations: Tōjūrō no Koi (1938 film) and Tōjūrō no Koi (1955 film)

- Shinju Fujin (

真珠 夫人 )

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Poulton, M. Cody (2010). A Beggar's Art: Scripting Modernity in Japanese Drama, 1900-1930. University of Hawai'i Press. p. 86.

- ^ Morichini, Giuseppe (1955). "Prewar and Postwar Japanese Fiction: Why the former is little known and why the latter should be better known in the West". East and West. 6: 138.

- ^ a b Morichini, Giuseppe (1955). "Prewar and Postwar Japanese Fiction: Why the former is little known and why the latter should be better known in the West". East and West. 6: 141.

- ^ Kojima, Chiaki (2004). "J.M. Synge and Kan Kikuchi: From Irish Drama to Japanese New Drama". Hungarian Journal of English and American Studies. 10: 99.

- ^ Morichini, Giuseppe (1955). "Prewar and Postwar Japanese Fiction: Why the former is little known and why the latter should be better known in the West". East and West. 6: 140.

- ^ Michiko, Suzuki (2012). ""Shinju fujin," Newspapers, and Celebrity in Taishō Japan". Japan Review.

- ^ Poulton, Cody M. (2010). "A Beggar's Art: Scripting Modernity in Japanese Drama": 87.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b Kojima, Chiaki (2004). "J.M. Synge and Kan Kikuchi: From Irish Drama to Japanese New Drama". Hungarian Journal of English and American Studies. 10: 108.

- ^ Poulton, Cody M. (2010). "A Beggar's Art: Scripting Modernity in Japanese Drama": 86.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Powell, Brian (2002). Japan's Modern Theatre. London: Japan Library. pp. 24–82. ISBN 1-873410-30-1.

- ^ Poulton, Cody M. (2010). A Beggar's Art: Scripting Modernity in Japanese Drama, 1900–1930. University of Hawaii Press. pp. 85–89. ISBN 9780824833411.

- ^ Michiko, Suzuki (2012). "Shinju fujin," Newspapers, and Celebrity in Taishō Japan. International Research Centre for Japanese Studies, National Institute for the Humanities. pp. 106–108.

- ^ Michiko, Suzuki (2012). "Shinju fujin," Newspapers, and Celebrity in Taishō Japan. International Research Centre for Japanese Studies, National Institute for the Humanities. p. 106.

- ^ Michiko, Suzuki (2012). "Shinju fujin," Newspapers, and Celebrity in Taishō Japan. International Research Centre for Japanese Studies, National Institute for the Humanities. p. 107.

- ^ Michiko, Suzuki (2012). "Shinju fujin," Newspapers, and Celebrity in Taishō Japan. International Research Centre for Japanese Studies, National Institute for the Humanities. p. 108.

- ^ Michiko, Suzuki (2012). "Shinju fujin," Newspapers, and Celebrity in Taishō Japan. International Research Centre for Japanese Studies, National Institute for the Humanities. p. 117.

- ^ a b Mack, Edward (2004). "Accounting for Taste: The Creation of the Akutagawa and Naoki Prizes for Literature". Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies. 64 (2): 299. doi:10.2307/25066744. JSTOR 25066744.

- ^ Mack, Edward (2004). "Accounting for Taste: The Creation of the Akutagawa and Naoki Prizes for Literature". Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies. 64 (2): 300. doi:10.2307/25066744. JSTOR 25066744.

- ^ Mack, Edward (2010). Manufacturing Modern Japanese Literature: Publishing, Prizes, and the Ascription of Literary Value. United States of America: Duke University Press. p. 186.

- ^ Mack, Edward (2004). "Accounting for Taste: The Creation of the Akutagawa and Naoki Prizes for Literature". Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies. 64 (2): 291–340. doi:10.2307/25066744. JSTOR 25066744.

- ^ Miller, Scott J. (2009). Historical Dictionary of Modern Japanese Literature and Theater. Scarecrow Press. p. 52.

- ^ a b "ペン

部隊 ". Kotobank (in Japanese). Retrieved July 24, 2023. - ^ Hutchinson, Rachael; Morton, Leith Douglas, eds. (2019). Routledge Handbook of Modern Japanese Literature. Routledge. ISBN 9780367355739.

- ^ Robertson, Jennifer (2002). "Yoshiya Nobuko: Out and Outspoken in Practice and Prose". In Walthall, Anne (ed.). The Human Tradition in Modern Japan. SR Books. p. 169. ISBN 9780842029124.

- ^ The Politics and Literature Debate in Postwar Japanese Criticism, 1945-52. Lexington Books. 2017. p. 284. ISBN 9780739180754.

- ^ "

日本 文学 報 国会 ". Kotobank (in Japanese). Retrieved July 24, 2023. - ^ "

菊池 寛 ". Kotobank (in Japanese). Retrieved July 24, 2023. - ^ WorldCat Identities Archived December 30, 2010, at the Wayback Machine:

菊池 寬 1888-1948

References

[edit]- Asai Kiyoshi. (1994). Kikuchi Kan (

菊池 寬 ) Tokyo: Shinchōsha. ISBN 9784106206436; OCLC 31486196

External links

[edit]- Author's entry at Aozora Bunko (in Japanese)

- Hiroshi Kikuchi's grave

- shinkyo shosetsu

- Madman on the Roof

- Works by or about Kan Kikuchi at the Internet Archive

- Works by Kan Kikuchi at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- 1888 births

- 1948 deaths

- Bisexual novelists

- Writers from Kagawa Prefecture

- Kyoto University alumni

- Japanese racehorse owners and breeders

- Bisexual male writers

- Japanese bisexual men

- Japanese LGBTQ novelists

- Japanese LGBTQ dramatists and playwrights

- Mahjong players

- Bisexual dramatists and playwrights

- 20th-century Japanese dramatists and playwrights

- People from Takamatsu, Kagawa

- Burials at Tama Cemetery