Tuoba

| Tuoba | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | |||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | |||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

The Tuoba (Chinese) or Tabgatch (Old Turkic: 𐱃𐰉𐰍𐰲, Tab

A branch of the Tanguts also bore a surname transcribed as Tuoba before their chieftains were given the Chinese surnames Li (

Names

[edit]By the 8th century,[1] the Old Turkic form of the name was Tab

Tuoba is the atonal pinyin romanization of the Mandarin pronunciation of the Chinese

Ethnicity and language

[edit]According to Hyacinth (Bichurin), an early 19th-century scholar, the Tuoba and their Rouran enemies descended from common ancestors.[13] The Weishu stated that the Rourans were of Donghu origins[14][15] and the Tuoba originated from the Xianbei,[16][17] who were also Donghu's descendants.[18][19] The Donghu ancestors of Tuoba and Rouran were most likely proto-Mongols.[20] Nomadic confederations of Inner Asia were often linguistically diverse, and Tuoba Wei comprised the para-Mongolic Tuoba as well as assimilated Turkic peoples such as Hegu (紇骨) and Yizhan (

Alexander Vovin (2007) identifies the Tuoba language as a Mongolic language.[22][23] On the other hand, Juha Janhunen proposed that the Tuoba might have spoken an Oghur Turkic language.[24] René Grousset, writing in the early 20th century, identifies the Tuoba as a Turkic tribe.[25] According to Peter Boodberg, a 20th-century scholar, the Tuoba language was essentially Turkic with Mongolic admixture.[26] Chen Sanping observed that the Tuoba language contains both elements.[27][28] Liu Xueyao stated that the Tuoba may have had their own language which should not be assumed to be identical with any other known languages.[29] Andrew Shimunek (2017) classifies Tuoba (Tabghach) as a "Serbi" (i.e., para-Mongolic) language. Shimunek's Serbi branch also consists of the Tuyuhun and Khitan languages.[30]

History

[edit]

The Tuoba were a Xianbei clan.[2][3] The distribution of the Xianbei people ranged from present day Northeast China to Mongolia, and the Tuoba were one of the largest clans among the western Xianbei, ranging from present day Shanxi province and westward and northwestward. They established the state of Dai from 310 to 376 AD[31] and ruled as the Northern Wei from 386 to 536. The Tuoba states of Dai and Northern Wei also claimed to possess the quality of earth in the Chinese Wu Xing theory. All the chieftains of the Tuoba were revered as emperors in the Book of Wei and the History of the Northern Dynasties. A branch of the Tuoba in the west known as the Tufa also ruled the Southern Liang dynasty from 397 to 414 AD during the Sixteen Kingdoms period.

The Northern Wei started to arrange for Chinese elites to marry daughters of the Xianbei Tuoba royal family in the 480s.[32] More than fifty percent of Tuoba Xianbei princesses of the Northern Wei were married to southern Chinese men from the imperial families and aristocrats from southern China of the Southern dynasties who defected and moved north to join the Northern Wei.[33] Some Chinese exiled royalty fled from southern China and defected to the Xianbei. Several daughters of the Xianbei Tuoba Emperor Xiaowen of Northern Wei were married to Chinese elites: the Han Chinese Liu Song royal Liu Hui married Princess Lanling of the Northern Wei;[34][35][36][37][34][38][39] Princess Huayang married Sima Fei, a descendant of Jin dynasty (266–420) royalty; Princess Jinan married Lu Daoqian; and Princess Nanyang married Xiao Baoyin (萧宝夤), a member of Southern Qi royalty.[40] Emperor Xiaozhuang of Northern Wei's sister the Shouyang Princess was wedded to Emperor Wu of Liang's son Xiao Zong.[41] One of Emperor Xiaowu of Northern Wei's sisters was married to Zhang Huan, a Han Chinese, according to the Book of Zhou (Zhoushu). His name is given as Zhang Xin in the Book of Northern Qi (Bei Qishu) and History of the Northern Dynasties (Beishi) which mention his marriage to a Xianbei princess of Wei. His personal name was changed due to a naming taboo on the emperor's name. He was the son of Zhang Qiong.[42]

When the Eastern Jin dynasty ended, Northern Wei received the Han Chinese Jin prince Sima Chuzhi as a refugee. A Northern Wei Princess married Sima Chuzhi, giving birth to Sima Jinlong (

Genetics

[edit]According to Zhou (2006) the haplogroup frequencies of the Tuoba Xianbei were 43.75% haplogroup D, 31.25% haplogroup C, 12.5% haplogroup B, 6.25% haplogroup A and 6.25% "other."[44]

Zhou (2014) obtained mitochondrial DNA analysis from 17 Tuoba Xianbei, which indicated that these specimens were, similarly, completely East Asian in their maternal origins, belonging to haplogroups D, C, B, A and haplogroup G.[45]

Chieftains of Tuoba Clan 219–376 (as Princes of Dai 315–376)

[edit]| Posthumous name | Full name | Period of reign | Other |

|---|---|---|---|

| 219–277 | Temple name: | ||

| 277–286 | |||

| 286–293 | |||

| 293–294 | |||

| 294–307 | |||

| 桓 Huán | 295–305 | ||

| 295–316 | |||

| None | 316 | ||

| None | 316 | ||

| 316–321 | |||

| 321–325 | |||

| 煬 Yáng | 325–329 and 335–337 | ||

| 329–335 and 337–338 | |||

| 338–376 | Regnal name: |

Legacy

[edit]

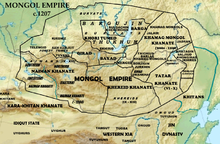

As a consequence of the Northern Wei's extensive contacts with Central Asia, Turkic sources identified Tabgach, also transcribed as Tawjach, Tawġač, Tamghaj, Tamghach, Tafgaj, and Tabghaj, as the ruler or country of China until the 13th century.[47]

The Orkhon inscriptions in the Orkhon Valley in modern-day Mongolia from the 8th century identify Tabgach as China.[47]

I myself, wise Tonyukuk, lived in Tabgach country. (As the whole) Turkic people was under Tabgach subjection.[48]

In the 11th century text, the Dīwān Lughāt al-Turk ("Compendium of the languages of the Turks"), Turkic scholar Mahmud al-Kashgari, writing in Baghdad for an Arabic audience, describes Tawjach as one of the three components comprising China.

Ṣīn [i.e., China] is originally three fold: Upper, in the east which is called Tawjāch; middle which is Khitāy, lower which is Barkhān in the vicinity of Kashgar. But now Tawjāch is known as Maṣīn and Khitai as Ṣīn.[47]

At the time of his writing, China's northern fringe was ruled by Khitan-led Liao dynasty while the remainder of China proper was ruled by the Northern Song dynasty. Arab sources used Sīn (Persian: Chīn) to refer to northern China and Māsīn (Persian: Machīn) to represent southern China.[47] In his account, al-Kashgari refers to his homeland, around Kashgar, then part of the Kara-Khanid Khanate, as Lower China.[47] The rulers of the Karakanids adopted Tamghaj Khan (Turkic: the Khan of China) in their title, and minted coins bearing this title.[49] Much of the realm of the Karakhanids including Transoxania and the western Tarim Basin had been under the rule of the Tang dynasty prior to the Battle of Talas in 751, and the Karakhanids continued to identify with China, several centuries later.[49]

The Tabgatch name for the political entity has also been translated into Chinese as Taohuashi (Chinese:

See also

[edit]- Chinese sovereign

- History of China

- Jin dynasty (266–420)

- Khitan people

- Ethnic groups in Chinese history

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Zhang (2010), p. 496.

- ^ a b c Grousset, Rene (1970). The Empire of the Steppes. Rutgers University Press. pp. 60–65. ISBN 0-8135-1304-9.

- ^ a b c d Holcombe, Charles (2001). The Genesis of East Asia: 221 B.C. - A.D. 907. p. 131. ISBN 978-0-8248-2465-5.

- ^ a b Brindley (2003), p. 1.

- ^ a b Sinor (1990), p. 288.

- ^ Zhang (2010), p. 496–497.

- ^ Zhang (2010), p. 485.

- ^ Zhang (2010), pp. 491, 493, 495.

- ^ Zhang (2010), p. 488.

- ^ "资治

通 鉴大辞典 ·上 编".㩉拔

氏 :(...) 鲜卑氏族 之 一 。即 "托 跋 氏 " - ^ Wang Penglin (2018), Linguistic Mysteries of Ethnonyms in Inner Asia, Lexington Books, p. 135, ISBN 978-1-4985-3528-1.

- ^ Zhang (2010), p. 489.

- ^ Hyacinth (Bichurin) (1950). Collection of information on peoples lived in Central Asia in ancient times. p. 209.

- ^ Golden, B. Peter (2013). "Some Notes on the Avars and Rouran". In Curta, Florin; Maelon, Bogdan-Petru (eds.). The Steppe Lands and the World beyond Them. Iaşi. p. 55.

- ^ Book of Wei. Vol. 103.

蠕蠕,

[Rúrú, offspring of Dōnghú, surnamed Yùjiŭlǘ]東 胡 之 苗裔 也,姓 郁 久 閭氏 - ^ Wei Shou. Book of Wei. Vol. 1

- ^ Tseng, Chin Yin (2012). The Making of the Tuoba Northern Wei: Constructing Material Cultural Expressions in the Northern Wei Pingcheng Period (398–494 CE) (PhD). University of Oxford. p. 1.

- ^ . Vol. 90.

鮮卑

[The Xianbei who were a branch of the Donghu, relied upon the Xianbei Mountains. Therefore, they were called the Xianbei.]者 ,亦 東 胡 之 支 也,別 依 鮮卑山 ,故 因 號 焉 - ^ Xu Elina-Qian (2005). Historical Development of the Pre-Dynastic Khitan. University of Helsinki.

- ^ Pulleyblank, Edwin G. (2000). "Ji

姬 and Jiang姜 : The Role of Exogamic Clans in the Organization of the Zhou Polity" (PDF). Early China. p. 20. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-11-18. - ^ Lee, Joo-Yup (2016). "The Historical Meaning of the Term Turk and the Nature of the Turkic Identity of the Chinggisid and Timurid Elites in Post-Mongol Central Asia". Central Asiatic Journal. 59 (1–2): 113–4.

- ^ Vovin, Alexander (2007). "Once again on the Tab

γ ač language". Mongolian Studies. XXIX: 191–206. - ^ Holcombe (2001). The Genesis of East Asia. p. 132. ISBN 978-0-8248-2465-5.

- ^ Juha Janhunen (1996). Manchuria: An Ethnic History. p. 190.

- ^ Steppes, Empire (1939). Turkic vigor-so marked among the first Tabgatch ruler. United States: René Grousset. ISBN 978-0-8135-0627-2.

- ^ Holcombe (2001). The Genesis of East Asia. p. 132. ISBN 978-0-8248-2465-5.

- ^ Chen, Sanping (2005). "Turkic or Proto-Mongolian? A Note on the Tuoba Language". Central Asiatic Journal. 49 (2): 161–73.

- ^ Holcombe (2001). The Genesis of East Asia. p. 248. ISBN 978-0-8248-2465-5.

- ^ Liu 2012, pp. 83–86.

- ^ Shimunek, Andrew (2017). Languages of Ancient Southern Mongolia and North China: a Historical-Comparative Study of the Serbi or Xianbei Branch of the Serbi-Mongolic Language Family, with an Analysis of Northeastern Frontier Chinese and Old Tibetan Phonology. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag. ISBN 978-3-447-10855-3. OCLC 993110372.

- ^ Grousset, Rene (1970). The Empire of the Steppes. Rutgers University Press. pp. 57. ISBN 0-8135-1304-9.

- ^ Rubie Sharon Watson (1991). Marriage and Inequality in Chinese Society. University of California Press. pp. 80–. ISBN 978-0-520-07124-7.

- ^ Tang, Qiaomei (May 2016). Divorce and the Divorced Woman in Early Medieval China (First through Sixth Century) (PDF) (A dissertation presented by Qiaomei Tang to The Department of East Asian Languages and Civilizations in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of East Asian Languages and Civilizations). Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University. pp. 151, 152, 153.

- ^ a b Lee 2014.

- ^ Papers on Far Eastern History. Australian National University, Department of Far Eastern History. 1983. p. 86.

- ^ Hinsch, Bret (2018). Women in Early Medieval China. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 97. ISBN 978-1-5381-1797-2.

- ^ Hinsch, Bret (2016). Women in Imperial China. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 72. ISBN 978-1-4422-7166-1.

- ^ Papers on Far Eastern History, Volumes 27–30. Australian National University, Department of Far Eastern History. 1983. pp. 86, 87, 88.

- ^ Wang, Yi-t'ung (1953). "Slaves and Other Comparable Social Groups During The Northern Dynasties (386-618)". Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies. 16 (3/4). Harvard-Yenching Institute: 322. doi:10.2307/2718246. JSTOR 2718246.

- ^ China: Dawn of a Golden Age, 200–750 AD. Metropolitan Museum of Art. 2004. pp. 30–. ISBN 978-1-58839-126-1.

Xiao Baoyin.

- ^ Ancient and Early Medieval Chinese Literature (vol. 3 & 4): A Reference Guide, Part Three & Four. BRILL. 22 September 2014. pp. 1566–. ISBN 978-90-04-27185-2.

- ^ Adamek, Piotr (2017). Good Son is Sad If He Hears the Name of His Father: The Tabooing of Names in China as a Way of Implementing Social Values. Routledge. p. 242. ISBN 978-1-351-56521-9.

... Southern Song.105 We read the story of a certain Zhang Huan

張 歡 in the Zhoushu, who married a sister of Emperor Xiaowu宣 武 帝 of the Northern Wei (r. - ^ China: Dawn of a Golden Age, 200–750 AD. Metropolitan Museum of Art. 2004. pp. 18–. ISBN 978-1-58839-126-1.

sima.

- ^ Zhou, Hui (20 October 2006). "Genetic analysis on Tuoba Xianbei remains excavated from Qilang Mountain Cemetery in Qahar Right Wing Middle Banner of Inner Mongolia". FEBS Letters. 580 (26): Table 2. doi:10.1016/j.febslet.2006.10.030. PMID 17070809. S2CID 19492267.

- ^ Zhou, Hui (March 2014). "Genetic analyses of Xianbei populations about 1,500–1,800 years old". Human Genetics. 50 (3): 308–314. doi:10.1134/S1022795414030119. S2CID 18809679.

- ^ No known given name survives.

- ^ a b c d e Biran 2005, p. 98.

- ^ Atalay Besim (2006). Divanü Lügati't Türk. Turkish Language Association, ISBN 975-16-0405-2, p. 28, 453, 454

- ^ a b Biran, Michal (2001). "Qarakhanid Studies: A View from the Qara Khitai Edge". Cahiers d'Asie centrale. 9: 77–89.

- ^ Rui, Chuanming (2021). On the Ancient History of the Silk Road. World Scientific. doi:10.1142/9789811232978_0005. ISBN 978-981-12-3296-1.

- ^ Victor Mair (May 16, 2022). "Tuoba and Xianbei: Turkic and Mongolic elements of the medieval and contemporary Sinitic states". Language Log. Retrieved 5 April 2024.

- ^ 习近

平 (2019-09-27). "在 全国 民族 团结进步表彰 大会 上 的 讲话". National Ethnic Affairs Commission of the People's Republic of China (in Chinese). Retrieved 5 April 2024.分立 如南北朝 ,都 自 诩中华正统;对峙如宋辽夏金 ,都 被 称 为"桃 花石 ";统一如秦汉、隋 唐 、元明 清 ,更 是 "六 合同 风,九州 共 贯"。

Sources

[edit]- Bazin, L. "Research of T'o-pa language (5th century AD)", T'oung Pao, 39/4-5, 1950 ["Recherches sur les parlers T'o-pa (5e siècle après J.C.)"] (in French) Subject: Toba Tatar language

- Biran, Michal (2005), The Empire of the Qara Khitai in Eurasian History: Between China and the Islamic World, Cambridge University Press

- Boodberg, P.A. "The Language of the T'o-pa Wei", Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies, Vol. 1, 1936.

- Brindley, Erica Fox (2003), "Barbarians or Not? Ethnicity and Changing Conceptions of the Ancient Yue (Viet) Peoples, ca. 400–50 BC" (PDF), Asia Major, 3rd Series, 16 (2): 1–32, JSTOR 41649870.

- Clauson, G. "Turk, Mongol, Tungus", Asia Major, New Series, Vol. 8, Pt 1, 1960, pp. 117–118

- Grousset, R. "The Empire of the Steppes: A History of Central Asia", Rutgers University Press, 1970, p. 57, 63–66, 557 Note 137, ISBN 0-8135-0627-1 [1]

- Lee, Jen-der (2014). "9. Crime and Punishment: The Case of Liu Hui in the Wei Shu". In Wendy Swartz; et al. (eds.). Early Medieval China: A Sourcebook. New York: Columbia University Press. pp. 156–165. ISBN 978-0-231-15987-6.

- Liu, Xueyao (2012). 鮮卑

列國 :大 興 安 嶺 傳奇 . ISBN 978-962-8904-32-7. - Pelliot, P.A. "L'Origine de T'ou-kiue; nom chinoise des Turks", T'oung Pao, 1915, p. 689

- Pelliot, P.A. "L'Origine de T'ou-kiue; nom chinoise des Turks", Journal Asiatic, 1925, No 1, p. 254-255

- Pelliot, P.A. "L'Origine de T'ou-kiue; nom chinoise des Turks", T'oung Pao, 1925–1926, pp. 79–93;

- Sinor, Denis (1990), "The Establishment and Dissolution of the Türk Empire", The Cambridge History of Early Inner Asia, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 285–316.

- Zhang Xushan (2010), "On the Origin of 'Taugast' in Theophylact Simocatta and the Later Sources", Byzantion, vol. 80, Leuven: Peeters, pp. 485–501, JSTOR 44173113.

- Zuev, Y.A. "Ethnic History Of Usuns", Works of Academy of Sciences Kazakh SSR, History, Archeology And Ethnography Institute, Alma-Ata, Vol. VIII, 1960, (In Russian)