Edo Castle (

| Edo Castle | |

|---|---|

| Chiyoda, Tokyo, Japan | |

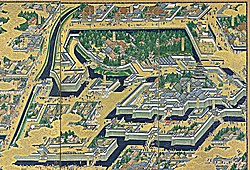

Edo Castle with surrounding residential palaces and moats, from a 17th-century screen painting. | |

| Type | Flatland |

| Site information | |

| Controlled by | Imperial Household Agency |

| Condition | Mostly ruins, parts reconstructed after World War II. Site today of Tokyo Imperial Palace. |

| Site history | |

| Built | 1457 |

| Built by | Ōta Dōkan, Tokugawa Ieyasu |

| In use | 1457–present (as Tokyo Imperial Palace) |

| Materials | granite stone, earthwork, wood |

| Demolished | The tenshu (keep) was destroyed by fire in 1657, most of the rest was destroyed by another major fire on 5 May 1873. In use as Tokyo Imperial Palace. |

| Garrison information | |

| Occupants | Tokugawa shōguns, Japanese emperors and imperial family since the Meiji era |

History

edit1) Ōoku 2) Naka-Oku 3) Omote 4) Ninomaru-Goten 5) Ninomaru 6) Momiji-yama 7) Nishinomaru 8) Fukiage 9) Kitanomaru 10) Unknown 11) Sannomaru 12) Nishinomaru-shita 13) Ōte-mae 14) Daimyō-Kōji

The warrior Edo Shigetsugu built his residence in what is now the Honmaru and Ninomaru part of Edo Castle, around the end of the Heian period (794–1185) or beginning of the Kamakura period (1185–1333). The Edo clan left in the 15th century as a result of uprisings in the Kantō region, and Ōta Dōkan, a retainer of the Ogigayatsu Uesugi family, built Edo Castle in 1457.

The castle came under the control of the Later Hōjō clan in 1524 after the Siege of Edo.[3] The castle was vacated in 1590 due to the Siege of Odawara. Tokugawa Ieyasu made Edo Castle his base after he was offered eight eastern provinces by Toyotomi Hideyoshi.[1] He later defeated Toyotomi Hideyori, son of Hideyoshi, at the Siege of Osaka in 1615, and emerged as the political leader of Japan. Tokugawa Ieyasu received the title of Sei-i Taishōgun in 1603, and Edo became the center of Tokugawa's administration.

Initially, parts of the area were lying under water. The sea reached the present Nishinomaru area of Edo Castle, and Hibiya was a beach.[clarification needed] The landscape was changed for the construction of the castle.[4] Most construction started in 1593 and was completed in 1636 under Ieyasu's grandson, Tokugawa Iemitsu. By this time, Edo had a population of 150,000.[5]

The existing Honmaru, Ninomaru, and Sannomaru areas were extended with the addition of the Nishinomaru, Nishinomaru-shita, Fukiage, and Kitanomaru areas. The perimeter measured 16 km.

The shōgun required the daimyōs to supply building materials or finances, a method shogunate used to keep the powers of the daimyōs in check. Large granite stones were moved from afar, the size and number of the stones depended on the wealth of the daimyōs. The wealthier ones had to contribute more. Those who did not supply stones were required to contribute labor for such tasks as digging the large moats and flattening hills. The earth that was taken from the moats was used as landfill for sea-reclamation or to level the ground. Thus the construction of Edo Castle laid the foundation for parts of the city where merchants were able to settle.

At least 10,000 men were involved in the first phase of the construction and more than 300,000 in the middle phase.[6] When construction ended, the castle had 38 gates. The ramparts were almost 20 meters (66 ft) high and the outer walls were 12 meters (39 ft) high. Moats forming roughly concentric circles were dug for further protection. Some moats reached as far as Ichigaya and Yotsuya, and parts of the ramparts survive to this day. This area is bordered by either the sea or the Kanda River, allowing ships access.

Various fires over the centuries damaged or destroyed parts of the castle, Edo and the majority of its buildings being made of timber.

On April 21, 1701, in the Great Pine Corridor (Matsu no Ōrōka) of Edo Castle, Asano Takumi-no-kami drew his short sword and attempted to kill Kira Kōzuke-no-suke for insulting him. This triggered the events involving the forty-seven rōnin.

After the capitulation of the shogunate in 1867, the inhabitants and shōgun had to vacate the premises. The castle compound was renamed Tokyo Castle (

A fire consumed the old Edo Castle on the night of May 5, 1873. The area around the old keep, which burned in the 1657 Meireki fire, became the site of the new Imperial Palace Castle (

The site suffered substantial damage during World War II and in the destruction of Tokyo in 1945.

Today the site is part of the Tokyo Imperial Palace. The government declared the area an historic site and has undertaken steps to restore and preserve the remaining structures of Edo Castle.

Appearance of Edo Castle

editThe plan of Edo Castle was not only large but elaborate. The grounds were divided into various wards, or citadels. The Honmaru was in the center, with the Ninomaru (second compound), Sannomaru (third compound) extending to the east; the Nishinomaru (west compound) flanked by Nishinomaru-shita (outer section) and Fukiage (firebreak compound); and the Kitanomaru (north compound). The different wards were divided by moats and large stone walls, on which various keeps, defense houses and towers were built. To the east, beyond the Sannomaru was an outer moat, enclosing the Otomachi and Daimyō-Kōji districts. Ishigaki stone walls were constructed around the Honmaru and the eastern side of the Nishinomaru. Each ward could be reached via wooden bridges, which were buffered by gates on either side. The circumference is subject to debate, with estimates ranging from 6 to 10 miles.[9]

With the enforcement of the sankin-kōtai system in the 17th century, it became expedient for the daimyōs to set up residence in Edo close to the shōgun. Surrounding the inner compounds of the castle were the residences of daimyōs, most of which were concentrated at the Outer Sakurada Gate to the south-east and in the Ōtemachi and Daimyō-Kōji districts east of the castle inside the outer moat. Some residences were also within the inner moats in the outer Nishinomaru.

The mansions were large and very elaborate, with no expenses spared to construct palaces with Japanese gardens and multiple gates. Each block had four to six of the mansions, which were surrounded by ditches for drainage.[10] Daimyōs with lesser wealth were allowed to set up their houses, called banchō, to the north and west of the castle.

To the east and south of the castle were sections that were set aside for merchants, since this area was considered unsuitable for residences. The entertainment district Yoshiwara was also there.

Gates

editEdo Castle was protected by multiple large and small wooden gates (mon), constructed in-between the gaps of the stone wall. There were 36 major gates. Not many are left on the outer moats, because they were a traffic hazard. Since the central quarter is now Tokyo Imperial Palace, some gates on the inner moats are well maintained and used as security check points.

In old days, "Ote-mon" was the main gate and the most heavily armed. There were 3 more gates you would go through after "Ote-mon" to reach the Shogun's residents . Today, "Nishinomaru-mon" is the main entrance to the Palace. However, the twin bridge "Nijubashi" in front of it is more famous than the gate itself, thus the Palace Entrance is often publicly referred to as "Nijubashi".

An eye-witness account is given by the French director François Caron from the Dutch colony at Dejima. He described the gates and courts being laid out in such a manner as to confuse an outsider. Caron noted the gates were not placed in a straight line, but were staggered, forcing a person to make a 90 degree turn to pass on to the next gate.[9] This style of construction for the main gates is called masugata (meaning "square"). As noted by Caron, the gate consisted of a square-shaped courtyard or enclosure and a two-story gatehouse which is entered via three roofed kōrai-mon. The watari-yagura-mon was constructed at adjacent angles to each side within the gate.[11] All major gates had large timbers that framed the main entry point and were constructed to impress and proclaim the might of the shogunate.

Garrison

editAccounts of how many armed men served at Edo Castle vary. The Spanish Governor-General of the Philippines Rodrigo de Vivero y Velasco gave an eye-witness account in 1608–1609, describing the huge stones that made up the walls and a large number of people at the castle. He claimed to have seen 20,000 servants between the first gate and the shōgun's palace. He passed through two ranks of 1,000 soldiers armed with muskets, and by the second gate he was escorted by 400 armed men. He passed stables that apparently had room for 200 horses and an armory that stored enough weapons for 100,000 men.[12]

Honmaru

editThe Honmaru (

Honmaru was destroyed several times by fire and reconstructed after each fire. The keep and main palace were destroyed in 1657 and 1863, respectively, and not reconstructed. Some remains, such as the Fujimi-yagura keep and Fujimi-tamon defense house, still exist.

The Honmaru was surrounded by moats on all sides. To the north separating Honmaru from the Kitanomaru were the Inui-bori and Hirakawa-bori, to the east separating the Ninomaru was the Hakuchō-bori, and to the west and south separating the Nishinomaru were the Hasuike-bori and Hamaguri-bori. Most of these still exist, although the Hakuchō-bori has partly been filled in since the Meiji era.

Kitahanebashi-mon

editKitahanebashi-mon (

Keep

editThe main keep or tower (known as the tenshu-dai (

Despite this, jidaigeki movies (such as Abarenbō Shōgun) set in Edo usually depict Edo Castle as having a keep, and substitute Himeji Castle for that purpose.

A non-profit "Rebuilding Edo-jo Association" (NPO

Honmaru Palace

editThe residential Honmaru Palace (

The Honmaru Palace was one story high, and consisted of three sections:

- The Ō-omote (Great Outer Palace) contained reception rooms for public audience and apartments for guards and officials;

- The Naka-oku (middle interior) was where the shōgun received his relatives, higher lords and met his counselors for the affairs of state; and

- Ōoku (great interior) contained the private apartments of the shōgun and his ladies-in-waiting. The great interior was strictly off-limits and communication went through young messenger boys.[17] The great interior was apparently 1,000 tatami mats in size and could be divided into sections by the use of sliding shōji doors, which were painted in elegant schemes.

Various fires destroyed the Honmaru Palace over time and was rebuilt after each fire. In the span from 1844 to 1863, Honmaru experienced three fires. After each fire, the shōgun moved to the Nishinomaru residences for the time being until reconstruction was complete. However, in 1853 both the Honmaru and Nishinomaru burned down, forcing the shōgun to move into a daimyō residence. The last fire occurred in 1873, after which the palace was not rebuilt by the new imperial government. Behind the Honmaru Palace was the main keep. Besides being the location of the keep and palace, the Honmaru was also the site of the treasury. Three storehouses that bordered on a rampart adjoined the palace on the other side. The entrance was small, made with thick lumber and heavily guarded. Behind the wall was a deep drop to the moat below, making the area secure.

Fujimi-yagura

editThe Fujimi-yagura (

Fujimi-tamon

editThe Fujimi-tamon (

Ishimuro

editNorth of the Fujimi-tamon is the ishimuro (

Shiomi-zaka

editShiomi-zaka (

Ninomaru

editAt the foot of the Shiomi-zaka on the eastern side of the Honmaru lies the Ninomaru (

Several renovations were carried out over the years until the Meiji era. A completely new garden has been laid out since then around the old pond left from the Edo period. Only the Hyakunin-bansho and Dōshin-bansho are still standing.

Dōshin-bansho

editThe dōshin-bansho (

Hyakunin-bansho

editThere is a big stone wall in front of the Dōshin-bansho, which is the foundation of the Ōte-sanno-mon watari-yagura keep. The long building to the left on the southern side of this foundation is the hyakunin-bansho (

Ō-bansho

editThe large stone wall in front of the Hyakunin-bansho is all that is left of the Naka-no-mon watari-yagura (Inner Gate Keep). This building to the inner-right side of the gate is the Ō-bansho (

Suwa-no-Chaya

editThe Suwa-no-Chaya (

Sannomaru

editThe sannomaru (

Bairin-zaka

editA steep slope, Bairin-zaka (

Hirakawa-mon

editHirakawa-mon (

Ōte-mon

editŌte-mon (

A fire in Edo destroyed the Ōte-mon in January 1657, but was reconstructed in November 1658. It was severely damaged twice, in 1703 and 1855, by strong earthquakes, and reconstructed to stand until the Meiji era. Several repairs were conducted after the Meiji era, but the damage caused by the September 1923 Great Kantō earthquake lead to the dismantling of the watari-yagura (

The watari-yagura was burnt down completely during World War II on April 30, 1945. Restoration took place from October 1965 through March 1967, to repair the kōrai-mon and its walls, and the Ōte-mon was reconstructed.

Tatsumi-yagura

editThe tatsumi-yagura (

Kikyō-mon

editOne of the few gates left of the Ninomaru is the kikyō-mon (

Nishinomaru

editThe nishinomaru (

Sakurada-mon

editProtecting the Nishinomaru from the south is the large Outer Sakurada-mon (

Seimon Ishibashi and Seimon Tetsubashi

editTwo bridges led over the moats. The bridges that were once wooden and arched, were replaced with modern stone and iron cast structures in the Meiji era. The bridges were once buffered by gates on both ends, of which only the Nishinomaru-mon has survived, which is the main gate to today's Imperial Palace.

The bridge in the foreground used to be called Nishinomaru Ōte-bashi (

After their replacement in the Meiji era, the bridge is now called Imperial Palace Main Gate Stone Bridge (

Today both bridges are closed to the public except on January 2 and the Emperor's Birthday.

-

Seimon Tetsubashi (Nijūbashi)

-

Seimon Ishibashi (Meganebashi)

Fushimi-yagura

editFushimi-yagura (

Sakashita-mon

edit(

Momijiyama

editMomijiyama (

Tokugawa Ieyasu built a library in 1602 within the Fujimi bower of the castle with many books he obtained from an old library in Kanazawa. In July 1693, a new library was constructed at Momijiyama (Momijiyama Bunko).

The so-called "Momijiyama Bunkobon" are the books from that library, which are preserved in the National Archives of Japan today. This group consists chiefly of books published during the Song dynasty, Korean books that were formerly in the possession of the Kanazawa Bunko library, books presented by the Hayashi family as gifts, and fair copies of books compiled by the Tokugawa government.[20][21]

Fukiage

editThe fukiage (

Inui-mon

editThe Inui-mon (

Hanzōmon

editThe Hanzōmon (

-

Inui-mon, former Nishinomaru Ura-mon

-

Hanzō-mon, former Wadakura Gate

Kitanomaru

editThe Kitanomaru (

Kitanomaru is surrounded by moats. The Inui-bori and Hirakawa-bori to the south separate it from the Honmaru and Chidorigafuchi to the west.

Derived place names in Tokyo

editMany place names in Tokyo derive from Edo Castle. Ōtemachi (

See also

editNotes

edit- ^ a b "Map of Bushū Toshima District, Edo". World Digital Library. 1682. Retrieved 6 May 2013.

- ^

熱海 市 教育 委員 会 (2009-03-25). "熱海 市内 伊豆 石 丁場 遺跡 確認 調査 報告 書 ". Comprehensive Database of Archaeological Site Reports in Japan. Retrieved 2016-09-02. - ^ Turnbull, Stephen (1998). The Samurai Sourcebook. Cassell & Co. p. 208. ISBN 1854095234.

- ^ Schmorleitz, pg. 101

- ^ Schmorleitz, pg. 103

- ^ Schmorleitz, pg. 102

- ^ "

皇居 -通信 用語 の基礎 知識 ".[user-generated source] - ^ Ponsonby-Fane, Richard A. B. (1956). Kyoto: The Old Capital of Japan, 794–1869, p. 328.

- ^ a b Schmorleitz, pg. 105

- ^ Schmorleitz, pg. 108

- ^ a b Hinago, pg. 138

- ^ Schmorleitz, pg 105

- ^ "What was inside the castle? | A close-up on Edo castle | EDO TOKYO Digital Museum - Historical Visit, New Wisdom".

- ^ "Tenshudai, Base of Edo Castle Keep | Search Details".

- ^ "Rebuilding "Edo-jo" Association". Retrieved 2008-09-17.

- ^ Daily Yomiuri NPO wants to restore Edo Castle glory March 21, 2013

- ^ Schmorleitz, pg. 104

- ^

二重橋 .世界 大 百科 事典 第 2版 (in Japanese). Retrieved 2013-07-12. - ^

明治 村 二重橋 飾 電燈 . Aichi Cultural Properties Navi (in Japanese). Aichi Prefecture. Retrieved 2013-07-12. - ^ AMAKO Akihiko (October 2004). "Catalogue of Donated Books: Chinese Books (Kizousho Mokuroku: Kanseki)". Kitamaru: Journal of the National Archives of Japan (37): 4–5. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 23, 2009. Retrieved January 12, 2012.

- ^ Tokugawa Memorial Foundation

References

editFurther reading

edit- De Lange, William (2021). An Encyclopedia of Japanese Castles. Groningen: Toyo Press. pp. 600 pages. ISBN 978-9492722300.

- Motoo, Hinago (1986). Japanese Castles. Tokyo: Kodansha. ISBN 0-87011-766-1.

- Ponsonby-Fane, Richard A. B. (1956). Kyoto: The Old Capital of Japan, 794–1869. Kyoto: The Ponsonby Memorial Society.

- Schmorleitz, Morton S. (1974). Castles in Japan. Tokyo: Charles E. Tuttle Co. pp. 99–112. ISBN 0-8048-1102-4.

通信 用語 の基礎 知識 (in Japanese). WDIC Creators Club. Retrieved January 12, 2012.

External links

edit- Rebuilding "Edo-jo" Association

- National Museum of Japanese History: Folding screens depicting scenes of the attendance of daimyo at Edo castle

- National Archives of Japan: Ryukyu Chuzano ryoshisha tojogyoretsu, scroll illustrating procession of Ryukyu emissary to Edo, 1710 (Hōei 7).

- National Archives of Japan: Ryuei Oshirosyoin Toranoma Shingoten Gokyusoku ukagai shitae, scroll showing artwork added to partitions of castle keep during reconstruction after 1844 fire, artist was Kanō Eitoku (1814–1891)

- Comprehensive Database of Archaeological Site Reports in Japan, Nara National Research Institute for Cultural Properties