Revolt of the Altishahr Khojas

You can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in Chinese. (October 2015) Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|

| Revolt of the Altishahr Khojas | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Khoja rebels and Qing soldiers fighting at the Battle of Yesil-kol-nor near Yashilkul Lake, 1759. Painted by Jean-Damascène Sallusti in 1764. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Altishahr Khojas |

Qing dynasty Badakhshan | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Khwāja Jihān[1] Burhān ud-Dīn[1] Abdul Karim ʿAbd ul-Khāliq 哈三 鄂斯 瑪呼斯 |

Qianlong Emperor Zhaohui (Manchu) Yarhašan (Manchu) Emin Khoja (Uighur) Yūsuf (Kumul) (Uighur) Namjal (Mongol) Shi Santai (Han) Fude (Manchu) Arigun (Manchu) Mingrui (Manchu) | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

Hojijan >10,000 Buranidun >5,000[2] |

c. 200,000 in the later stages (Khalkha Mongols, Dzungars, Eight Banners, Green Standard Army, Mongolian Eight Banners, Hui Battalion ( | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| Unknown | Unknown | ||||||

The Revolt of the Altishahr Khojas (Chinese:

After the Qing conquest of Dzungaria at the end of the Dzungar–Qing Wars in 1755, the Khoja Brothers were released from Dzungar captivity whereupon they began to recruit followers in the Western Regions around Altishahr. Not long afterwards, the Khoit-Oirat prince Amursana rose up against the Qing and the Khoja Brothers used the opportunity to seize control of the south west part of Xinjiang.

In 1757, Hojijan killed the Qing Vice General Amindao (

With the revolt pacified, the Qing completed the reintegration of their territory in one of Qianlong's Ten Great Campaigns. The end of the conflict saw the restoration of the territory south of the Tian Shan to Qing control meaning that the Qing now controlled the whole of Xinjiang.

After the appointment of an Altishahr Grand Ministerial Attache the Xinjiang area remained peaceful for the next 60 years.

Background

[edit]The White Mountain Khoja and the Zhuo Clan

[edit]The ancestor of the Khoja brothers was Ahmad Kasani (1461–1542) also known as Makhdūm-i`Azam, "the Great Master" of the Central Asian Naqshbandi Sufi Sect. Kasani claimed to be a descendant of Muhammad through his daughter whose offspring were known as the Khojas (

In the middle of the Ming dynasty (1368-1644), the Black Mountain Khoja received approval from the ruling Yarkand Khanate for the Altishahr or Tarim Basin area south of the Tian Shan range in the Western Regions to convert to Islam. In the mid-17th century, the White Mountain Khoja leader Muhammed Yusef Khoja (d. 1653) came from Central Asia to Kashgar to prosleytze only to be driven out by the Yarkand Khanate and the Black Mountain Khojas. Yusef Khoja's son Afaq Khoja escaped to Hezhou (

In 1680, during the reign of the Qing Kangxi Emperor, the Dzungars under Galdan Boshugtu Khan, with the help of Afaq Khoja, invaded Yarkand and deposed the ruling Khan, Ismail Khan. Galden then installed Abd ar-Rashid Khan II as Khan of Yarkand. Afaq Khoja soon afterwards fled from Yarkand following discord with the new ruler. Two years later, in 1682, riots erupted in Yarkand causing Abd ar-Rashid Khan II to flee to Ili. His younger brother Muhammad Amin then became Khan.[6]

The riots of around 1682[7] led to the overthrow of Muhammad Amin Khan by the followers of Afaq Khoja, whose son Yahya Khoja became the ruler of Yarkand and Kashgar.[6]

Two years later, Afaq Khoja died and the Kashgar region sank into a civil war involving the Yarkand Khanate, White Mountain Khoja, Kyrgyz and the local begs.

After Tsewang Rabtan succeeded to the leadership of the Dzungar Khanate in 1697 he imprisoned the descendants of the Altishahr Khojas in what is now known as Ili Kazakh Autonomous Prefecture. When Galdan Tseren came to power in 1727, he gave Black Mountain Khoja, Daniyal (Persian: خواجہ دانیال; simplified Chinese: 达涅尔; traditional Chinese:

Dawachi and Amursana split

[edit]After Galdan Tseren died in 1745, the Dzungar Khanate fell into internecine warfare. In the end, Dawachi, who was the grandson of Khong Tayiji Tsewang Rabtan's cousin Tsering Dhondup (

However, in 1754, Dawachi and Amursana quarreled and the latter defected to the Qing, taking with him 5,000 soldiers and 20,000 women and children.[8] He then demanded permission to travel to Beijing and seek the emperor's assistance in defeating Dawachi and retaking Ili and neighbouring Kashgar. Amursana's persuasive manner and Qianlongs's ambition and love for military renown meant that in the end he agreed,[9] throwing in a princedom of the first degree (

Surrender of the Dzungars

[edit]

In the first lunar month of 1755, two units of the Qing army, each consisting of 25,000 men carrying two months' of rations per man,[10] entered Dzungaria from two different directions to destroy Dawachi's army and retake the territory. The Northern Route Army under commander Ban Di comprised Border Pacifying Vice-general of the Left Wing Amursana, Amban Sebutangbalezhu'er and Mukden Commander Alantai while Border Pacifying Vice-general of the Right Wing Salar 薩喇勒 and Minister of the Interior (內

On 8 April 1755, Buranidun surrendered to Salar's Western Route Army saying "At the time of Galdan Tseren, my father was imprisoned and thus far I have not been released. I will bring perhaps 30 of my households to surrender to the emperor and become his servants"[A][11] Not long afterwards, the Younger Khoja, Hojijan, surrendered to Ban Di with Hadan.[12]

In May, Qing forces entered Huocheng County in Ili. Ban Di planned to send Buranidun to Beijing for presentation to the emperor while Hojijan would be kept in Ili in the care of the nomadic Muslim Taranchi.

The Us Beg[B] Khojis (霍集斯; Huò jísī) received orders from Ban Di to establish sentry posts on the mountain passes into the Tarim Basin. When a further order to prepare for war arrived, Khojis' troops hid in the woods while his younger brother was dispatched to take wine and horses to Davachi—who when he arrived was seized along with his men and his son Lobja. The prisoners were then escorted under guard to the Qing barracks by Khojis and 200 of his men.[13] Dawachi's capture effectively marked the end of the Dzungar Khanate.

At the same time, Kashgar Black Mountain Khoja Yusuf (second son of Daniyal) marched north. Aksu's Hakim Beg Abd-Qwabu (Khojis' elder brother) suggested to Ban Di that the Qing Army send an emissary along with them during the transport of the Khoja brothers to Kashgar. Abodouguabo further announced his appointment as ruler of the area at the behest of Qianlong.[14] As a result, Ban Di dispatched the Imperial Bodyguard, Tuoluntai (

Amursana's Revolt

[edit]With Dawachi on his way to Beijing as a captive, Amursana now saw an opportunity to establish himself as the new Dzungar Khan with control of the four Oirat tribes of Dzungaria. Qianlong had other ideas. The emperor knew that Amursana had long had his sights set on Dzungaria but "had not dared to do anything rash."[C][16] As a result, before the military expedition to Ili had set out and fearing the rise of a new Mongolian empire, Qialong had proclaimed that the four Oirat clans of Dzungaria would be resettled in their own territory each with their own Khan appointed directly by Beijing. Amursana spurned the offer of khanship over the Khoits and told Ban Di to inform the Emperor that he wanted control of all the Oirats. Amursana received orders to return to Beijing but sensing that if he left Ili he might never be able to return, on 24 September 1755 he escaped from his escort en route to the Qing imperial resort at Chengde[8] and returned to Tarbaghatai (now Tacheng in Xinjiang, China), 400 kilometres (250 mi) east of Ürümqi. The Ili zaisang or chief and his lamas then seized the city. In the chaos, Hojijan led a band of Uyghur and escaped from the Ili basin. Other White Mountain Khojas imprisoned in Dzugaria including Ḥusein (Chinese:

In March 1756, West Pacifying General Celeng Celeng arrived with the Western Route Army to recapture Ili. Amursana fled into the Kazakh Khanate as the tables were once again turned on him. Hojijan and Buranidun united the local population in May, then the Younger Khoja killed Amursana's envoy. Tuoluntai defected to the rebel side and was sent to ascertain the strength of the Qing Garrison in Ili.[19]

Course of events

[edit]

Hojijan sought independence from the Qing regime and told the local clan leaders: "I have just escaped from the slavery of the Dzungars; now it seems I must surrender to the Qing and pay tribute. Although inferior to ruling the region, working the land and defending the cities is sufficient resistance."[D] Buranidun was unwilling to take on the Qing Army: "We were once Humiliated by Dzungaria; Without the aid of the Qing military, how could we have returned to our homeland? We must not turn our backs on kindness and fight with Qing."[E][20]

An envoy sent by Hoijijan then killed Chagatai Khan descendant and former Yarkand chief, Yike Khoja (

Paintings

[edit]-

Khojas troops at the Battle of Yesil-kol-nor (1759). Painting by Jean-Damascène Sallusti.

-

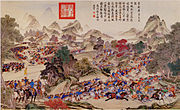

Zhao Hui was unable to take Yarkand, moved east but was forced to retreat by the rebels, who lay siege to him at the Black River. In 1759, Zhao Hui learnt of the imminent arrival of relief troops, and so stormed the rebel town and brought the rebellion to an end. By Giuseppe Castiglione.

-

Battle of Qurman, 1759. General Fu De, on his way to relieve the siege of Khorgos, was suddenly attacked by an enemy force of 5,000 Muslim cavalry and with less than 600 men Fu De defeated the Muslims. By Jean-Damascène Sallusti.

-

Battle of Tonguzluq, 1758. General Zhao Hui tries to take Yarkand but is defeated. By Giuseppe Castiglione.

-

Battle of Qos-Qulaq, 1759. Chinese General Ming Rui defeats the Khoja army in Qos-Qulaq (north of Kara-Kul, Tajikistan). By Giuseppe Castiglione.

-

Qing defeat the Khoja at Arcul, after they had retreated following the battle of Qos-Qulaq, 1759. By Jean Denis Attiret.

-

The Chinese army defeats the Khoja brothers (Burhān al-Dīn and Khwāja-i Jahān) in Yesil-Kol-Nor (present-day Yashil Kul, Tajikistan), 1759. By Jean-Damascène Sallusti.

-

The Khan of Badakhsan asks to surrender, 1759. By Jean-Damascène Sallusti.

-

The prisoners are presented at the palace gate of Wumen. The emperor is also offered the head of the Khoja Huo Jizhan. By Jean-Denis Attiret.

-

The emperor in the suburbs personally receives news of the officers and soldiers who distinguished themselves in the campaign against the Muslim tribes. By Jean-Damascène Sallusti.

-

A victory banquet given by the emperor to the distinguished officers and soldiers of the Huibu Rebellion (1758–1759). By Giuseppe Castiglione.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Original Chinese: "

我 父 縛 來 為 質 ,至 今 並 不 將 我 等 放 回 。我 等 情 願 帶 領 屬 下 三 十餘戶投降大皇帝為臣僕" - ^ During Qing dynasty, the government appointed a beg as the effective ruler of each town in the Muslim areas (Huibu;

回 部 ) of Xinjiang. - ^ Original Chinese: "

料 伊 亦 不 敢遽爾 妄行" - ^ Original Chinese: "

甫 免 為 厄 魯特(準 噶爾)役 使 ,今 若 投 誠 ,又 當 納 貢 。不 若 自 長 一方 ,種 地 守 城 ,足 為 捍禦。" - ^ Original Chinese: "

從前 受辱於厄魯特,非 大國 (清 )兵力 ,安 能 復歸 故 土 ?恩 不可 負 ,即 兵力 亦 斷 不能 抗 。" - ^ Original Chinese: "

我 兄弟 自 祖父 三 世 ,俱被準 噶爾囚 禁 。荷 蒙 天恩 釋放 ,仍為回 部 頭目 ,受恩深 重 。若 爾 有 負 天朝 ,任 爾 自 為 ,我 必不能 聽從 "

References

[edit]- ^ a b

佐 口 透 . "カシュガル=ホージャ家 の後裔 " (in Japanese). - ^ 《18-19

世紀 新 疆社會 史 研究 》,76頁 (18th-19th Century Xinjiang Social Research, Page 76) (in Chinese) - ^ Arabinda Acharya; Rohan Gunaratna; Wang Pengxin (2010). Ethnic Identity and National Conflict in China. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 24. ISBN 978-0-230-10787-8.

- ^ Itzchak Weismann (25 June 2007). The Naqshbandiyya: Orthodoxy and Activism in a Worldwide Sufi Tradition. Routledge. p. 82. ISBN 978-1-134-35305-7.

- ^ Johan Elverskog (6 June 2011). Buddhism and Islam on the Silk Road. University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 224. ISBN 978-0-8122-0531-2.

- ^ a b Ahmad Hasan Dani; Vadim Mikhaĭlovich Masson; Unesco (2003). History of Civilizations of Central Asia: Development in contrast : from the sixteenth to the mid-nineteenth century. UNESCO. ISBN 978-92-3-103876-1.

- ^ Liu & Wei 1998, p. 215.

- ^ a b c d Hummel 1943, p. 10.

- ^ Alikuzai 2013, p. 302.

- ^ Perdue 2009, p. 272.

- ^ "

正編 卷 十 (Compilation Scroll 10)". 《平定 準 噶爾方略 》 [The Dzungaria Strategy]. 1772. - ^ Liu & Wei 1998, p. 242.

- ^ Dani & Masson 2003, p. 201.

- ^ 《

和 卓 傳 》漢 文節 譯本 [Khoja Annals - Chinese Translation]. p. 113. - ^ 《

和 卓 傳 》漢 文節 譯本 [Khoja Annals - Chinese Translation]. p. 121. - ^ 《

高 宗 實錄 》 [Gaozong (Qianlong) True Record] (in Chinese). Vol.卷 四 百 八 十 九 (Scroll 489). - ^ "

額 色 尹 傳 (Eseyin Biography)". 《外 藩 蒙 古 回 部 王 公表 傳 》 [Biographies of the Muslim Nobility Beyond Mongolia] (in Chinese). Vol.卷 一 百 一 十 七 (Scroll 117). - ^ Zhun'ge'er Qi (1772). "

正編 卷 二 十 九 ,乾 隆 二 十 一年六月己酉引宰桑固英哈什哈語 (Compilation Scroll 29; Qianlong 21st Year, Sixth Month)". 《平定 準 噶爾方略 》 [The Dzungaria Pacification Plan] (in Chinese). - ^ Zhun'ge'er Qi (1772). "

正編 卷 三 十 二 ,乾 隆 二 十 一 年 閏 九 月 丙午 (Compilation Scroll 29; Qianlong 21st Year, Ninth Month)". 《平定 準 噶爾方略 》 [The Dzungaria Pacification Plan] (in Chinese). - ^ Zhun'ge'er Qi (1772). "

正編 卷 五十八 (Compilation Scroll 58)". 《平定 準 噶爾方略 》 [The Dzungaria Pacification Plan] (in Chinese). - ^ Zhun'ge'er Qi (1772). "

正編 卷 三 十 三 (Compilation Scroll 33)". 《平定 準 噶爾方略 》 [The Dzungaria Pacification Plan] (in Chinese). - ^ 《18-19

世紀 新 疆社會 史 研究 》 [Research into the Social History of Xinjiang in the 18-19th Century] (in Chinese). pp. 40, 43.

Bibliography

[edit]- Alikuzai, Hamid Wahed (2013). A Concise History of Afghanistan in 25 Volumes. Vol. 14. Trafford Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4907-1441-7.

- Dani, Ahmad Hasan; Masson, Vadim Mikhaĭlovich (2003). History of Civilizations of Central Asia: Development in contrast : from the sixteenth to the mid-nineteenth century. UNESCO. ISBN 978-92-3-103876-1.

- Hummel, Arthur W. Sr., ed. (1943). . Eminent Chinese of the Ch'ing Period. United States Government Printing Office.

- Perdue, Peter C (2009). China Marches West: The Qing Conquest of Central Eurasia. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-04202-5.

- Liu, Zhengyin; Wei, Liangtao (1998). 《

西域 和 卓 家族 研究 》 [Research Paper on the Khoja Clan of the Western Regions] (in Chinese).中国 社会 科学 出版 社 (China Social Sciences Publishing). ISBN 978-7500423782.