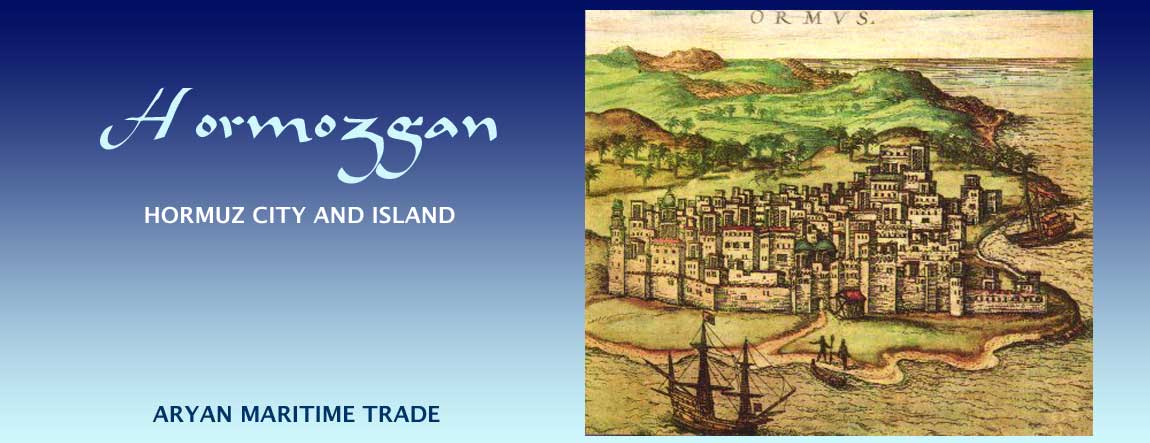

Banner image: 1577 CE Etching of Ormus in Civitates Orbis Terrarum by Frans Hogenberg and Georg Baum in several volumes 1572 - 1618, at the Biblioteca Nacional de Portugal

ContentsHormozgan's History & Zoroastrian Connections |

Hormozgan's History & Zoroastrian Connections

Related reading:

» Early Parsi History. Escape from Iran

» Maneckji Limji Hataria's Mission to Iran

Hormuz In Zoroastrian History

Located in the north of the narrow Straits of Hormuz, known locally as the Tanga-e Hormuz, Old Hormuz City and the Island of Hormuz, home to New Hormuz City, were located in what is today the southern Iranian province of Hormozgan. [Hormuz is also spelt Hormoz.] The old port-city stood strategically at the entrance to the Persian Gulf to its west and at the gateway to the Arabian Sea to its east. More so that any other port city in the world, the sea and land trade routes that radiated from Hormuz spread like tentacles across and Asia, Africa and Europe. Hormuz stood at the cross roads of history as well. Right up to the medieval ages, Hormuz was a destination port for world travellers such as Italian Marco Polo, Moroccan Ibn Battuta and Zheng He from China.

In our page on Aryan Trade and as we will read in these pages, Iranians had over the ages had developed considerable expertise in international trade and travel. Hormozgan was a junction point of land and sea trade routes. In these pages we will become explorers ourselves. We will seek to find out more about Hormuz, the history of the region, its role in Aryan trade, and its connections to Zoroastrian heritage.

During the Arab invasion of Iran in the 7th century CE, a number of Iranians fled before the advancing Arab armies to Hormuz, a southern Iranian city-port) where they mounted a last stand. When defeat was inevitable, those who could flee dispersed by land and sea. As chronicled in Futuh-ul-Buldan (an Arabic book by Ahmad Ibn Yahya Ibn Jabir Al Biladuri, a ninth century CE writer), some fled some by land to Sistan and others by ship to the Markan coast of Baluchistan. (Also see Flight from Iran.)

According to the Qissa-e Sanjan, a Parsi legend, Hormuz was last Iranian home of a group of Zoroastrians before they embarked on a harrowing sea voyage to India around the 8th century CE.

|

| 1747 stylized map of Hormuz Island and New Hormuz City in Johann Caspar Arkstee and Henricus Merkus' Allgemeine Historie der Reisen zu Wasser und Lande, oder Sammlung aller Reisebeschreibungen, Leipzig. Image credit: Historic Cities Click to view a larger image |

If the city of Hormuz was the last home in Iran from a group of fleeing Zoroastrians, the Island of Hormuz was Maneckji Limji Hataria's first stop on his rescue mission to Iran.

Maneckji Limji Hataria (1813-1890 CE), was the representative of the Society for the Amelioration of the Conditions of the Zoroastrians in Persia, a Bombay-based charitable society set up by the Parsees of India to provide assistance for their co-religionists who continued to live in Iran. Hataria recounts in his report, A Parsi Mission to Iran (1865), that he set sail for Iran from the shores of India on March 31, 1854. On the 'Isle of Ormaz' (the English translation of his Persian original), he found an observatory constructed by ancient Iranian, which had a device to study the movements of nine planets.

We can find no mention of the observatory today. In Arkstee and Henricus Merkus' 1747 map of the Island of Hormuz, some of the structures to the right and bottom on the map of Hormuz Island are not part of modern maps. What we do find in surviving historical literature are reports is that Hormuz suffered much devastation at the hands of a succession of invaders and raiders. Regrettably, locals had no regard for whatever ruins survived the destruction for we read that stones from the structures and ruins on Hormuz Island were used for constructing buildings in Bandar Abbas. We also read that ancient sites near today's mainland city Minab have been ploughed over.

While there is much to lament in what is irretrievably lost, there is also much to celebrate in the heritage that survives and awaits further discovery. Part of that discovery lies in the records of the fascinating role Hormuz played in international Aryan trade. Hormuz's fame had reached the far reaches of the European, African and Asian continents. Legends of Hormuz's trade, great wealth and exotic bazaars had reached the ears of Marco Polo (1254-1324) in Italy, Ibn Battuta (1304-c.1368).

in Morocco and Zheng He (1371-1435) in China. For they all came to Hormuz and they have all left us with records of their visits. We recount some of their words in these pages. While meagre, the visible signs of the region's heritage that can be seen by the keen observer today. That heritage, a Zoroastrian heritage, is also embedded in the names of Hormozgan's cities and we shall start our exploration with an examination of these names.

Zoroastrian Heritage Embedded in the names of Hormozgan and its Cities

|

| Map of Lower Persian Gulf & Hormozgan Province with Hormuz Island circled in red. Base map courtesy Microsoft Encarta. All modifications © K. E. Eduljee 2010 |

The Name Hormuz

Today, Hormuz (Hormuz) survives as the name of a historic island in the Iranian province of Hormozgan.

Every Zoroastrian knows that Hormuz or Hormozd is also a Middle Persian word or term for God in Zoroastrianism. Hormozd itself is the a derivative of the original Avestan / Old Iranian term Ahura Mazda via an intermediate derivative, Ahurmazd (transition between Old and Middle Persian). This transition happened over a passage of hundreds, if not thousands, of years.

The name Hormuz, Hormozd or Hormuzd (sometimes shortened from Homozdyar or Hormuzdiar meaning a friend of God) is not uncommon amongst Zoroastrians.

That the name Hormuz has survived as the name of a historic Iranian island is itself a miracle and perhaps Zoroastrians should be grateful to those who try and seek other non-Zoroastrian explanations for the name, for in so doing, the Zoroastrian origins of the name is obfuscated in a long list of imagined possibilities thereby giving the fanatics - who would like to destroy and erase everything Zoroastrian - an excuse to let the name stand.

The European version of the name Harmozeia was used by Arrian (see below) as a name for the region some 2000 years ago, and it is likely that the name Hormuz, or a related name, predated Arrian's writing. Hormuz as a name for the region is therefore a very old name indeed.

[Name derivatives: Hormuzd>Hormuz. Hormuzdiar>Hormuzdia>Hormuzia. Hormuz or Hormuzia>Harmozeia]

The Name Hormozgan

Hormozgan is today a southern province of Iran. The name shares the ending -gan with names like the festival Mehergan. This author takes the suffix -gan to mean dedicated to, honouring or celebrating. The implications of the name Hormozgan are therefore many. In being 'dedicated to God' or 'honouring God' or 'dedicated to doing God's work', the implication is that the region is divinely blessed - what in English may be described as God's country. Though such a flattering description may not have applied to the whole region of Hormozgan, nevertheless, at one point in history -during the Zoroastrian era - the description did apply to Old Hormuz city and the surrounding region, known to history as the Paradise of Persia. We will further discuss the basis of this reputation below.

The Name Mughistan

Moroccan traveller Ibn Battuta (1304-c.1368) wrote in his travelogue, "I travelled next to the country of Hormuz. Hormuz is a town on the coast, also called Mughistan." Ibn Battuta's Mughistan (Moghistan) was an alternative name for the country of Hormuz, today's Hormozgan. It is a name that continued to be used on European maps in the 18th and 19th century (see maps below). Mughistan / Moghistan by definition means the land of the Mugh / Mogh. Mugh (derived from magha), means a Zoroastrian priest - known to the West as a magus (Old Persian magush). The plural is mughan as in pir-e mughan / moghan, the hoary and wise magi. However, the Muslims used the name Magian for all Zoroastrians - not just Zoroastrian priests.

In the allegory of classical Persian poetry of Hafez and Rumi, the mugh were also associated with wine-selling, though the deeper meaning of that allegory association implied a free-person and free-thinker in juxta-position to those prohibited from selling or drinking wine. Given that Hormozgan was once the home of a large Zoroastrian community, it is not surprising that Hormozgan was called Mughistan - the land of the Zoroastrians, freedom and liberty.

|

The Name Gabroon / Gabrun - City of the Free

Today's Bandar Abbas, the capital city of Hormozgan Province, was previously known as Gabroon. Various attempts have been made to explain the name Gabrun and its derivatives including it being derived from 'gomruk' meaning customs (as in customs duties). Below, this author offers an explanation for the name Gabroon that he has not heard this elsewhere.

Bandar Abbas, meaning Port Abbas, is a relatively new name for the port-city being the name given to it after Shah Abbas (with help from the English) took back control of the port from the Portuguese in 1614 CE. The Portuguese had seized control of the port as well as Hormuz Island a hundred years earlier. Prior to the port-city being called Bandar Abbas, foreigners understood the name to be Gomberoon [John Fryer (1672-1681)], Gombroon [Jean Baptiste Tavernier (1631-1668)], Gombrun [Sir Thomas Herbert (1628)], Goobrun (not-quoted), Gameron [John Struys (1647-1672)], Gameroon [Wikipedia, not-quoted], Gamron (see etching to the right), and Gamrun (Dumper, Stanley not-quoted) amongst other versions.

This author proposes these European versions were a corruption of the local name Gabroon or Gabrun.

|

| Etching of port Gabrun, called Gamron by the artist (16th century?) |

Given that the region was known as Mughistan - meaning land of the Zoroastrians - and that Gabr or Gabrun was the term that replaced Mugh, this author further proposes that the principal city of Mughistan came to be called Gabroon via the following process:

Muslims came to use Gabr as a derogatory word by for Zoroastrians. Gabruni (cf. 'Iruni' used for 'Irani' in Zoroastrian colloquialism) means of, or belonging to, the Gabr. For instance, Gabruni evolved into a derogatory name given by Muslims to the the language of the Gabrun, the old language of the Zoroastrians, namely, the Dari spoken by Yazdi and Kermani Zoroastrians. Despite the use of the word in a derogatory sense by Muslims, the origins of the word Gabr may stem from the Middle Persian (Pahlavi) term for a man, a free man, gabra [cf. A. V. William Jackson in Zoroastrian Studies (1928), and Encyclopaedia Iranica]. The meaning free-man coincides with Hafez and Rumi's allegorical use of the term Mugh to mean a free-man and a free-thinker. Jackson suggests a link between gabr and the Pahlavi texts' use of the terms Mog-gabra and Moagoi'gabra, which in Pazand became Mago-i mart, meaning Magian man. Despite the negative manner in which Muslims appropriated the word, Zoroastrians can take back ownership and accept the label with honour for it distinguishes free-thinking Zoroastrians from those who were not free to think for themselves - slaves to a crushing ideology.

In closing, we note that Muslim and non-Muslim writers alike have tip-toed all around the root meaning of the names Hormozgan, Mughistan and Gabrun, either to insult, not to insult, or to simply bury the true roots by using versions of the name by piling on other explanations. But even the negative connotations cannot obliterate the deep rooted heritage Hormozgan shares with Zoroastrians and Zoroastrianism - and we suspect there are many who are secretly happy to let that old and authentic Iranian connection survive.

Hormozgan as Paradise

Henry Yule in his English translation of Marco Polo's (1254-1324) travels, The Book of Ser Marco Polo (London, 1875), quotes a Lieutenant Kempthorne as saying: "It (old Hormuz city and its environs) is termed by the natives the Paradise of Persia. It is certainly most beautifully fertile, and abounds in orange-groves, and orchards containing apples, pears, peaches, and apricots; with vineyards producing a delicious grape, from which was at one time made a wine called amber-rosolli... ." (Vol./Bk. 1, Chap. 19, pgs. 117-118.) Yule quotes one theory that amber-rosolli may have derived from ambar-e rasul, meaning prophet's bouquet, but that such a label would be too bold a name even for Persia. Yule believes that Sir H. Rawlinson's suggestion that the name is derived from ambar-e asali, meaning 'honey bouquet' is more plausible.

Yule also quotes a Colonel Pelly as writing, "The district of Minao is still for those regions singularly fertile. Pomegranates, oranges, pistachio nuts, and various other fruits grow in profusion. The source of its fertility is of course the river, and you can walk for miles among lanes and cultivated ground, partially sheltered from the sun."

Add to this description general prosperity brought on by trade, the attendant comfort and luxury, the bustling bazaars and rare spices as well as Hormuz being a place where one could meet people from all over the known world - people with their fascinating tales and exotic wares - and we can very well imagine why Hormuz may have been called God's country. The paradise-like splendour and high living standards of Hormuz Island's city are universally described by old-time travellers, and we recount their observations at different points in our narrative.

As with our recounting of Zoroastrian heritage elsewhere in the traditional Aryan lands, we are compelled to once again report with sadness, that while Hormozgan still has its own claim to beauty, it can no longer lay claim to these most superlative of descriptions that described it in the past: God's country, the Paradise of Persia. We will leave it to the reader to surmise the reasons why.

Hormozgan's Early History

In present-day Hormozgan, there is a town called Minab (see below) located some 80 km east of Bandar Abbas and some 25 km inland. The soil of its environs hold rich history in its womb. The city of Old Hormuz was located close to Minab.

Surveys by Stein* have identified approximately 27 archaeological sites in the area extending from Minab to about 40 km northward and 30 km westward (Prickett** p. 1270) and the area surveyed may be considered as the Hormuz hinterland. The findings at these sites are noted in our next page section on Old Hormuz and Minab.

[* M. A. Stein, Archaeological Reconnaissances in North-Western India and South-Eastern Iran, London, 1937. **Williamson-Prickett (M. E. Prickett, Ph.D. diss., Harvard University, Cambridge, 1986. As cited by D. T. Potts at Encyclopaedia Iranica.]

Stone Age c 150,000 BCE

According to a 2006 report at CIAS and elsewhere, Siamak Sarlak, archaeologist and head of an Iranian excavation team in Minab and Roodan stated that "84 historical relics have been unearthed during the excavations in Minab port so far, some of which date back to the ancient Stone Age (some 150,000 years ago)." The article contains no further supporting information.

c 5000 - 4000 BCE

K-9, the earliest of the 27 Old Hormuz heartland sites noted above has yielded shards comparable to Lapui-ware discovered at Tal-e Bakun in Pars Province's Marv Dasht and dated to the early fourth-millennium BCE (Prickett** p. 1270). Most of the Minab prehistoric sites have been dated on the basis of parallels to Tepe Yahya in east-central Kerman province.

c 3000 - 2000 BCE

Painted black-on-orange wares characteristic of period IVC at Tepe Yahya (c 3100-2900 BCE) was found at one prehistoric site, K 14.

c 1500 - 800 BCE

|

| Stone tablet with Elamite inscription found near Bandar Abbas. Photo credit: various |

A number of prehistoric sites such as K 84, 96, 98, 100, 104-6, 109, 110B, 112, 124-26, 130G, and 137, have been yielded artefacts and layers dated to the Iron Age (1300 to 900 BCE) and Parthian-period (see below).

c 1500 BCE Tablet in Elamite Discovered In Hormozgan

An indication of the wide contact the Hormozgan region had with other regions early in its history is the recent discovery of a 6 x 7 cm black stone tablet with nine lines of Elamite cuneiform inscription in the vicinity of Sarkhoon (Khun Sorkh?) village near Bandar Abbas. The tablet is thought to date back to 1500 BCE. Since the tablet is a small fragment of a larger inscription, we do not know what the tablet states or where it was from (for instance Hormozi traders might have adopted the widely used Elamite language for trade). Elam survives today as the Iranian province of Ilam with its centre well over a thousand kilometers to the northwest of Hormozgan. Its eastern lands (today's Pars province) became part of Persia sometime around the 7th century BCE and its language became one of the official languages of the Persian empire. Elam and its city state of Susa were destinations along the Aryan trade roads that extended from Central Asia to Babylon and Sumer.

700 BCE - 300 CE

Williamson and Prickett, cited above, have also recorded the presence of red-polished ware thought to originate in the Indian sub-continent in two sites near Minab (Whitehouse and Williamson, Fig. 7). While these artefacts are often said to date from the first three centuries CE, they have in fact been used from 1st century BCE to the 5th century CE (Orton, p. 46). Given that Darius and Alexander both launched naval expeditions from the Indus River towards the Hormuz region in the 6th and 4th centuries BCE, the archaeological evidence corroborates the evidence in literature of very early trade between the regions. Artefacts at the sites also date to the Parthian-period (250 BCE-230 CE).

For much of this period, the kingdom of Hormuz (Harmozeia) was often a vassal state of Kerman (Carmania) which was in turn a vassal state of Persia. Together, Hormuz and other Aryan kingdoms were part of Greater Iran.

Darius the Great's Maritime Expeditions (6-5th cent. BCE)

We do not known when Hormozgan region or Hormuz Island first became a maritime trading centre as part of the Aryan trade routes. What we do know from Herodotus (c 485 - 420 BCE) Histories 4.44 is that Achaemenian Persian King Darius the Great (522-486 BCE) sought to establish maritime links with several coastal states across the known world, and to this end, Darius launched a naval expedition under the charge of Scylax, a Greek, who journeyed to Egypt, probably as far as Libya. Herodotus also informs that that Darius' maritime expeditions "made use of the sea in those parts" of the Indus river, and from there all Asia, except East Asia which was "found to be similarly circumstanced with Libya." If Darius "made use of the sea" from India to Libya, trade was probably a significant component of the 'use', thereby extending the potential reach of the Aryan trade routes from the borders of China to Libya. It is also within the realm of possibilities that one branch of the maritime trade routes passed through the straits of Hormuz which would be a natural junction point with the Aryan land trade routes.

Alexander's Maritime Expedition (4th cent. BCE) Recorded by Arrian

Arrian, or more completely Lucius Flavius Arrianus (c 86 - 160 CE), a Roman of Greek ethnicity, wrote the Anabasis of Alexander, an often quoted account of Alexander of Macedonia. As well, Arrian authored Indica a description of Nearchus' voyage from India following Alexander's conquest of Persia and Central Asia up to the Indus river - the traditional boundary of the Persian empire. Alexander appointed Nearchus (c 325-326 BCE), an Admiral of a fleet charged with conducting a reconnaissance mission to the mouth of the Indus river and from there to the mouth of river Euphrates at the head of the Persian Gulf. Nearchus recorded his voyage in detail and his account (the original is lost) was used by Arrian in writing Indica. Nearchus had a fleet of thirty-three galleys, some with two decks, additional transport ships, and about 2000 men. Nearchus and his fleet sailed down the Indus in about four months, escorted on either bank of the river by Alexander's armies, and after spending seven months in exploring the Delta, he set sail for the Persian Gulf. It is in Indica that we find the first Western mention of Hormuz called Harmozeia by Arrian. Arrian's account of Nearchus's voyage to Hormuz is as follows:

|

After a harrowing voyage along the coast of Baluchistan (Gedrosia), often reaching points of near starvation despite plundering towns along the way, Nearchus landed at the mouth of the river Anamis (Minab) on the shores of Hormozgan (Harmozeia), which was then a sub-region, likely a vassal kingdom, of Kerman (Carmania). Arrian states in Indica (33; JRGS V. 274) that Nearchus found the country of Harmozeia 'a kindly one, and very fruitful in every way' except that there were no olives. The weary mariners landed and enjoyed this pleasant rest from their toils. Nearchus then marched inland for five days to meet up with Alexander after the latter's land crossing of the Baluchistan (Gedrosian) desert. Nearchus returned to Hormuz and continued his mission, sailing as far as the river Euphrates which empties into the upper reaches of the Persian Gulf. From there he went overland to rejoin Alexander who had by this time (early 324 BCE) arrived overland at Susa, the legendary winter capital of Darius the Great.

Alexander's conquests were for the main part the lands that had been part of the Persian empire under Darius the Great. Alexander would have had access to the various accounts about Darius, the extent of Darius' empire as well as Darius' many endeavours some 150 years earlier. Alexander's maritime expedition commanded by Nearchus which started from the upper reaches of the Indus, emulates Darius' maritime expedition that he placed under the Greek Scylax. That Nearchus headed towards Hormuz as an interim destination to link up with Alexander via land gives us added reason to believe that Hormuz was already a known and established junction point of land and sea routes (making Hormuz admirably suited as a trading centre). We may further surmize that for Hormuz to have been functioning as a port during Nearchus' visit, it must have existed at least during the latter Achaemenian period (550-320 BCE) if not earlier.

Post Arab Invasion Historical Milestones

Hormuz Resistance to the Arabs

We find Old Hormoz mentioned in connection with resistance to the Arab invasion in an Arabic book Futuh-ul-Buldan by Ahmad Ibn Yahya Ibn Jabir Al Biladuri, a ninth century CE writer who died c 892.

Al Biladuri states, "He (Mujasa bin Masood) conquered Jeraft (Jiroft, Kerman) and having proceeded to Kerman (city), subjugated the city and made for Kafs (Hormozgan) where a number of Persians, who had emigrated, opposed him by at Hormuz (the port of Kerman). So he fought with and gained victory over them and many people of Kerman fled away by sea. Some of them joined the Persians at Makran and some went to Sagistan (Sistan)." (cf. Translation from the Arabic by Rustam Mehrdaban Aga as quoted in an article The Kissah-e-Sanjan by Dr. Jivanji Modi in the Journal of the Iranian Association Vol VII, No. 3. June 1918.)

Mongol-Turkic (Tartar) Chagatai Khanate Raids

While the Mongols never occupied Hormoz, Marco Polo starts his section on Persia (Yule, Chapter 13) by noting, "Persia is a great country, which was in old times very illustrious and powerful; but now the Tartars (Mongols and their Turkic allies) have wasted and destroyed it."

In the mid 1200s the Mongol armies of Genghis Khan (c 1162-1227) aided by his Turkic allies (not to be confused with Ottoman Turks)had overrun most of Central Asia and North-Eastern Iran. Neighbouring territories they did not subsequently rule were plundered and often destroyed indiscriminately as a way of instilling fear in others. Hormozgan, or Mughistan as it was then known, was one of those regions that the Tartars frequently raided. Before his death Ghengis Khan, divided his empire between his four sons Ogedei, Chagatai, Tolui, and Jochi. Central Asia and northern Iran was given to Chagatai Khan (c 1185-1241), Genghis Khan's second son. While the Chagatai Khanate existed from up to 1687, not long after after Chagatai's death in 1242, namely by 1270, his khanate became one of the weakest of the Mongol states, and its rulers were mere figureheads for more ambitious rulers, such as Timur / Tamerlane, Kaidu (Qaidu), and Kaidu's son Chapar. Kaidu was a great-grandson of Genghis Khan. Kublai Khan was his uncle.

If the Tartar raids in the first half 1300s were for booty, according to Ali of Yazd, the Tartar Timur Leng (or Tamerlane 1336 - 1405 CE) of Samarkand ordered an expedition against the coastal towns of near Old Hormoz (latter half of 1300s?). Seven castles in its neighbourhood were all taken and burnt: Kalah Mina - the Castle of the Creek at Old Hormoz, Tang Zandan, Kushkak, Hisar-Shamil, Kalah Manujan, Tarzak and Taziyan.

Migration from Old Hormuz to New Ormaz / Hormoz City & Island

Peter Rowland in Essays on Hormoz (2006) reports that the wealth of the mainland Hormoz city attracted raids so often, that the merchants moved their operations (and presumably especially their warehouses) to the relative safety of Hormuz Island.

In 1296, Mir Bahdin Ayaz Seyfin (Amir Baha-al-Din Ayaz) took over the government of Hormuz after the murder of its previous ruler Nosrat and in doing so became the fifteenth king of Hormuz. According to A. W. Stiffe* (quoting an account written by Turan Shah**, king of the island of Hormuz in 1347-78), Turks (probably Tartars) "broke into the kingdom of Kerman and from there to that of Ormuz. The wealth they found tempted them to come so often that the , no longer able to bear the oppression, left the mainland and went to the island of Broct, by the Portuguese called Quixome (now called Jeziret at Tawilah, or after the town on it, Kesm)."

[*Article The Island of Hormuz (Ormuz) in Geographical Magazine, London, (Apr. 1874, vol. 1) pp. 12-17]

[**The Hormuzian prince Turanshah, a very interesting name of an Old Iranian historical perspective, wrote a Shahnameh, a 'Book of

Kings' not to be confused with Ferdowsi's epic of the same name. It was written some time after 1350 and was probably destroyed by the British and the Safavids during the war of 1622. But some parts of this chronicle were translated into Portuguese by Pedro Teixeira and the Portuguese version has become the starting point for many later studies.

Stiffe writes, "After some days Ayaz went about that part of the Gulf seeking some convenient island where he might settle with his people. He came to the then desert island of Gerun (Organa of Nearchus), and resolved to beg this island of the king of Keys (Kais, Qais), to whom it belonged, as did all the others in the gulf of Persia**. The island of Kais, at that time a kingdom, has still the ruins of a considerable city on its north side... . Having obtained of Neyn, king of Keys, the island of Gerun, Ayaz and his people went to live there and in remembrance of their native country, they gave it the name Homruz. Ayaz was the fifteenth king of Old Hormuz and the first king of New Hormuz.

[**According to authors Berthold Spuler [in Die Mongolen in Iran, Leiden (19850, at pages 118, 122-27], and Arnold Wilson [in The Persian Gulf (1959) at pages 102-4], because of continued Chagatai Khanate incursions against Southeast Persia, Ayaz with help from the rulers of neighbouring Fars, moved the entire population and possessions of Old Hormoz to the small island of Jarun, which he bought from the Fars rulers.]

Henry Yule informs us that Friar Odoric, around the year 1321 found Hormuz "on an island some 5 miles distant from the main." We conclude from this that the migration to New Hormoz had already taken place by 1321.

Portuguese Attack On Hormoz (Island?)

At the end of September 1501, a Portuguese fleet under Alfonso de Albuquerque (q.v.) attacked Hormuz, defeated the local fleet, and killed many people. He made the town of Jarun a Portuguese tributary and imposed on its people an annual payment of 15,000 ašrafis (q.v.). He also started the building of a fort, but trouble with four captains in his fleet forced him to leave the island in February 1508 before the fort was completed. He returned in March 1515 and established Portuguese rule, which lasted for over a hundred years.

Ruy Freyre, Portuguese Commander 1624 citing the complete destruction of the fortress at Hormoz with not one stone left standing:

"This fortress was built on the summit of a hill out of range of our artillery, and they did not wish to submit since there was a garrison of 400 Persian soldiers within; on the contrary, they fired some volleys of musketry into our Armada which caused us the loss of 8 Portuguese killed, besides many others wounded.

"It seemed to the General that this war was becoming unduly prolonged, so he ordered 300 well-armed Portuguese under their ordinary Captains, together with a force of 400 Lascarians under the command of Manoel Cabaco, to be disembarked in three separate places, with orders to put to the sword all whom they should find within the fortress.

"These men speedily effected their several landings, and stepped ashore amidst a storm of shot that was fired from the fortress with the intention of hindering the disembarkation. Having landed, they climbed up the hillside to the fortress, which they carried by assault in the first rush, cleaving a way with their hand-grenades. They put to the sword all those they found therein, without mercy to age or sex, and then they burnt the City and razed the fortress, not leaving anything with life in that site nor one stone upon another. All this was done with the loss of only 6 Portuguese and 12 Lascarians slain, and a few more wounded.

"After this bellicose fury was finished, the General sailed along the coast, and doubling Cape Mossandam he arrived at Camufa, where he was well received by the inhabitants of the City, since all its townsmen had formerly served as sailors in our Armadas of rowing-vessels at Ormuz, and they were a people who had never been unfaithful to us."

In 1617 de Silva y Figueroa estimated the number of households in Hormoz at between 2,500 and 3,000, and of these, 200 were Portuguese.