Mythological Background

After the Greeks defeated Troy, they took many of the Trojan women captive. The women would be given to the Greek leaders as slaves. Among the Trojan women captives were King Priam’s wife, Queen Hecuba, and two of her daughters – the prophetess Cassandra and her sister Polyxena. Priam and Hecuba had sent their youngest son, Polydorus, to the court of King Polymestor of Thrace for safe-keeping, along with a great treasure of gold.

When the Greeks wanted to sail home, the spirit of the dead hero Achilles prevented them from leaving Troy by stopping the winds. Achilles’ spirit wanted to be honored by the human sacrifice of the most beautiful of the princesses of Troy, Polyxena.

King Polymestor of Thrace turned out to be a disloyal friend to the Trojans: he kept the gold treasure, killed young Prince Polydorus, and threw his body into the sea. Eventually it washed up onshore near the Greek encampment, and was brought to his mother Hecuba.

Notes

In lines 251-295, Odysseus has come to bring Polyxena to be sacrificed at Achilles’ tomb. Hecuba reminds him about an incident before the end of the war: Odysseus had sneaked into Troy in disguise as a spy, but Helen recognized him and pointed him out to Hecuba. Odysseus had supplicated Hecuba to let him escape unharmed, and the queen had done so. Hecuba now in turn supplicates Odysseus to let Polyxena be spared. She points out that the real injustice done to Achilles was done by Helen, who should therefore be the victim sacrificed to Achilles. Hecuba reminds Odysseus that he owes her a favor in exchange for his life, and asks that he convince the Greeks to spare her daughter.

In lines 299-333, Odysseus responds to Hecuba. He is willing to spare her life, but will not ask the Greeks to spare Polyxena. Odysseus argues that any man’s sacrifice of his own life for the cause of his people earns him the right to be honored after death. He points out that there are Greek parents and brides grieving for dead Greek heroes. The Chorus of captive Trojan women interject a brief comment that slavery is a curse because the enslaved, overpowered by the force of their conquerors, must endure any wrong done to them.

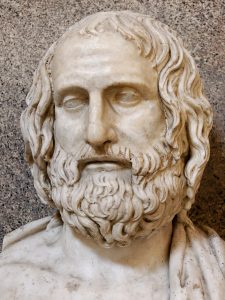

About the Author

There is little reliable evidence about the life of Euripides, and nearly nothing from his lifetime. Most ancient sources about his life say that he was born in the year when Athens won the Battle of Salamis, 480 BCE. He presented his first tragedies in 455, and won his first victory in a drama competition in 441. He won only four victories in drama competitions during his career as a playwright. Contemporary comic playwrights (Aristophanes and others) parodied and ridiculed his work more than they did the work of any other Athenian literary figure. This suggests that, although Euripides may not have won often, people paid attention to his work. We know he died before January of 405, because Aristophanes’ comedy, The Frogs, which refers to Euripides’ death, was staged in that month and year.

Evidence about Euripides’ activity as a tragedian is reliable: for the dramatic contests each year, an inscription in stone recorded the contestants’ names, their plays, and any prizes they won. The inscriptions were copied, most notably by Aristotle and his students, then later by the Alexandrian scholars. The Alexandrians also collected copies of as many plays as they could find, compiling them into collections later used by medieval copyists. Alexandrian scholars apparently had copies of 78 plays by Euripides, 70 tragedies and 8 satyr plays, and knew titles for 14 more plays. 19 of these plays survive; one play attributed to him the Rhesus, may not be his work. At least two non-dramatic poems are ascribed to Euripides: a victory ode (now fragmentary) in honor of Alcibiades’ victories in the 416 BCE Olympic Games’ chariot races, and an epitaph in honor of the Athenians who died in Sicily during the Peloponnesian War.

Evidence from Aristotle’s reference to a lawsuit in which Euripides was involved indicates that the poet was fairly well-off in terms of wealth – not surprising in that he had enough time available to him to be able to write plays without any guarantee of financial success from them.

A remark attributed to Euripides’ fellow writer of tragedies, Sophocles, reflects the difference between Sophocles’ work and Euripides’: Sophocles is said to have claimed that he showed people as they ought to be (or ought to be shown), whereas Euripides showed them as they really were. Euripides treated the old myths, his source materials for his plots, as if they were stories about real everyday people. Often in his plays he depicts his characters at their crisis moments, revealing their weaknesses.

A recurrent element in Euripides’ dramas is a sense of defeat and disappointment, possibly reflecting Euripides’ own feelings at the reception of his plays. He tended to focus on the weak and oppressed, the despised and misunderstood members of society: usually women, slaves, captives, strangers, and (to Greek eyes) barbarians (i.e., non-Greeks). Thus, another recurrent motif in Euripides is that of a character’s desire to escape his/ her situation. Euripides had his faults in constructing tragedies: scenes of pathos sometimes turn into scenes of sentimentality; his plays show signs of hasty or sloppy composition; and he sometimes attempted to get too much into a single character or situation. Faulty as his plays might be, however, his characters are unforgettable.

Although various reasons are given for Euripides’ decision to go to Macedon in 408 BCE, it is a guess as to which reason – his wife’s infidelity, his annoyance at having to compete against inferior poets, disdain for failing to win first prize in dramatic contests – is the true one. It should be noted that other Athenian poets and artists also accepted invitations from Archelaus, the archon of Macedon, at around the time Euripides went there. Whether Euripides was going into self-imposed exile, or intended to make only a temporary visit, is unknown. In any event, he died in Macedon. The funerary inscription on the cenotaph erected to him in Athens states that he was buried in Macedon.

Source

Euripides. Euripides I: Iphigeneia at Aulis, Rhesus, Hecuba, Daughters of Troy, Helen. Transl. A.S. Way. Loeb Classical Library. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1987.

Image: Bust of Euripides. Marble, Roman copy after a Greek original from ca. 330 BC, Museo Pio-Clementino, Sala delle Muse, Vatican. Photo by Marie-Lan Nguyen (2009) https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Euripides_Pio-Clementino_Inv302_n2.jpg