Erga -Works and Days

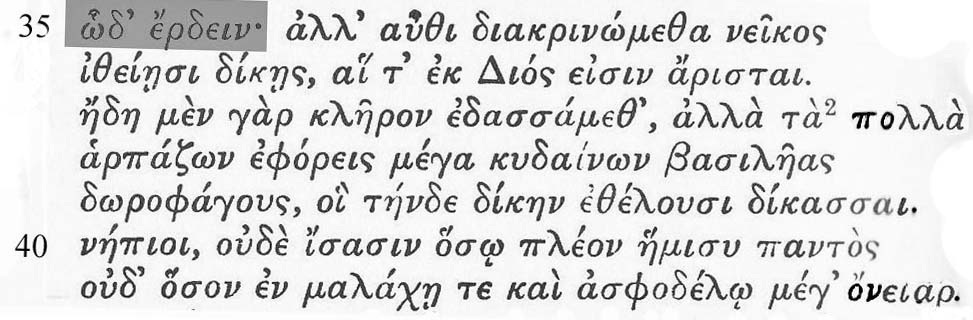

Hesiod — Original Text

Translation by Dorothea Wender

(Lines 35-40: Hesiod addresses his brother Perses about their dispute) Come, let us settle our dispute at once,

And let our judge be Zeus, whose laws are just.

We split our property in half; but you

Grabbed at the larger part and praised to hea

The lords wh

Eaters of bribes. The fools! They do not know

That half may be worth more by far than whole,

Nor h

Lines 265-285: Another warning to Perses to do right, because Zeus sees all, and has ordained the law of right justice.

The eye of Zeus sees all, and understands,

And when he wishes, marks and does not miss

How just a city is, inside. And I

Would not myself be just, nor have my son

Be just among bad men: for it is bad

To be an honest man where felons rule;

I trust wise Zeus to save me from this pass.

But you,

Follow the just, avoiding violence.

The son of

That animals and fish and winged birds

Should eat each other, for they have no law.

But mankind has the law of Right from him,

Which is the better way. And if one knows

The law of Justice and proclaims it, Zeus

Far-seeing vies one great prosperity.

But if a man, with knowledge, swears an oath

Committing perjury and harming right

Beyond repair, his family will be cursed

In after times, and come to nothing. He

Who keeps his oath will benefit his house.

Translated by Dorothea Wender

Biographical and Historical Information

Hesiod (fl. Late 8c BCE)

We know very little for certain about Hesiod. In his poetry he refers to himself as a shepherd and peasant small farmer. We do know that he came from the town of Ascra in Boeotia, a region in Greece north of the area around Athens. He lived at a time when the Greek-speaking world was dominated by aristocratic landlords, so that small farmers such as himself had to struggle to survive.

In the didactic poem Erga – called the Works and Days in English – Hesiod uses a particular instance in his life (his dispute with his brother Perses over the division of their late father’s land) as a springboard into a discussion of the injustice of aristocratic landowners and of all the powers to which human life is subject.

However, despite Hesiod’s conviction that life in his contemporary age is often hard and miserable, he sees a light beyond all the darkness in the form of Justice (Dikē). The opposite of Justice is Hubris, which Albin Lesky (History of Greek Literature, p. 103) identifies as “unrelenting violence”. Lesky asserts that Hesiod should not be seen as a social revolutionary: his aim was not to change the social structure of his society, but to heal and purify it via an absolute morality. Hesiod should be included in any catalogue of social in/justice poets, because his poetry shows that he had a strong and admittedly prejudiced interest in what he perceived as the rights and wrongs done by his fellow humans.

Hesiod’s poetry uses the dactylic hexameter meter, the same as used in the Homeric epics, the Iliad and the Odyssey. Ancient sources attribute a number of other poems to Hesiod, but only one survives more or less intact – the Theogony, a genealogical poem about the origin of the gods.

A note of interest: The best-known version of the story of Pandora comes from Hesiod’s poetry (not included here because of length). Other sections of the W&D make it clear that Hesiod is a misogynist, so it is not surprising that in the course of discussing life’s hardships and his unhappiness over situations that could be perceived as instances of social injustice, Hesiod engages in what to modern eyes might appear an act of social injustice by using the Pandora story as a way of laying the blame for all of humanity’s problems on women. Hesiod’s views on this subject seem not to have been unusual in the ancient world; it would be many centuries before the idea of social justice for all humans was developed.

Sources

Lesky, Albin. A History of Greek Literature. Tr. James Willis and Cornelis de Heer. 2nd ed. (1966)

Hesiod, Works and Days and Theogony. Tr. Dorothea Wender. Penguin Books (1973, repr. 1976)

Hesiod, Homeric Hymns, Epic Cycle, Homerica. Tr. Hugh G. Evelyn-White. Revised ed. Loeb Classical Library (1936, repr. 1998).