Feb 20, 2019 © Ulrich Theobald

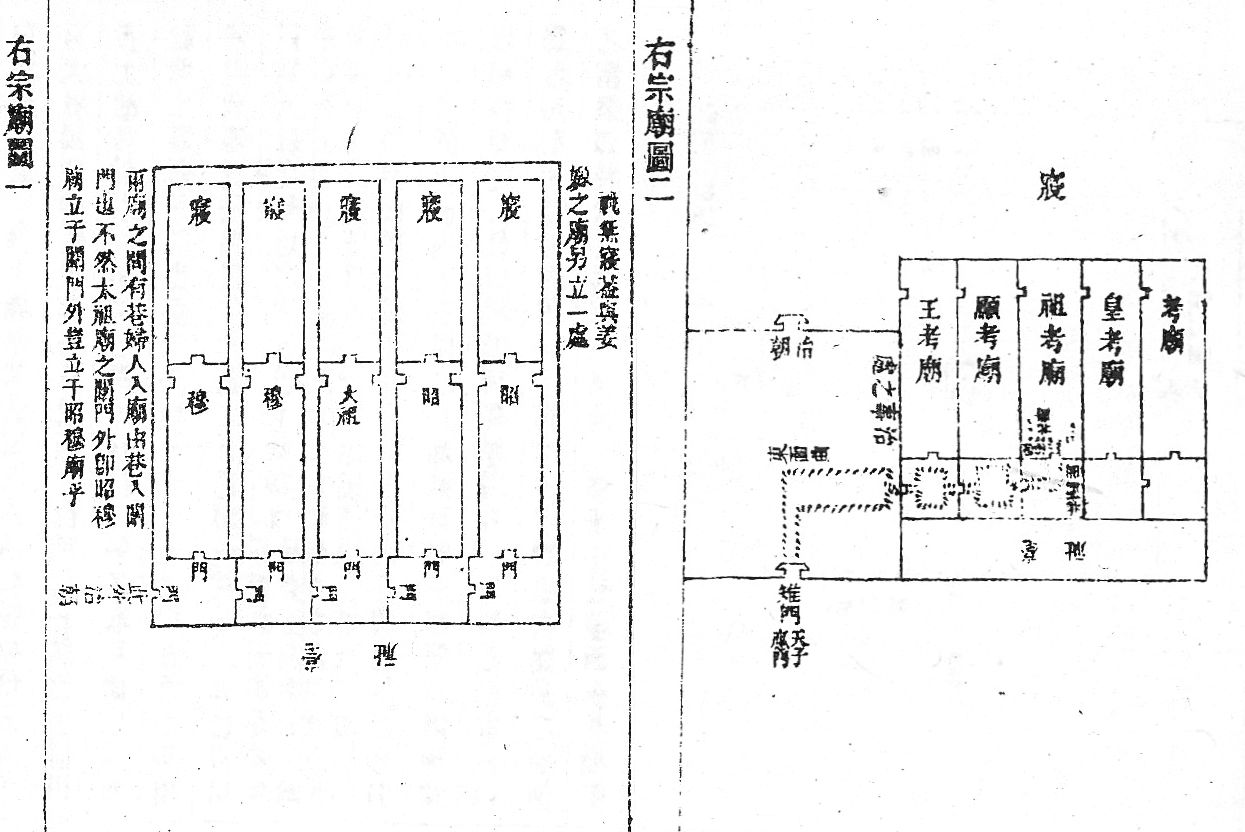

The zhao-mu system (zhao-mu zhidu 昭穆制度) is mainly known for the arrangement of spirit tablets in an ancestral temple. It dates from the early Western Zhou period 西周 (11th cent.-770 BCE) and found its major form in the 8th century. It is usually described as an arrangement in which the high ancestor (taizu 太祖, gaozu 高祖) is placed in the middle, while younger ancestors were placed crosswise to the left and right, but in a turned-U shape. In the original form, each of the seven ancestors venerated by the then-present king of the Zhou dynasty 周 (11th cent.-221 BCE) was given a separate building, but from the Han period 漢 (206 BCE-220 CE) on, ancestors were assembled in one single temple hall.

The chapter "Royal regulations" (Wangzhi 王制) in the ritual Classic Liji 禮記 says,

Quotation 1. The zhao-mu system in ancestral temples

| 天子七廟,三昭三穆,與大祖之廟而七。諸侯五廟,二昭二穆,與大祖之廟而五。大夫三廟,一昭一穆,與大祖之廟而三。士一廟,庶人祭於寢。 |

(The ancestral temple of) the Son of Heaven embraced seven fanes (or smaller temples); three on the left and three on the right, and that of his great ancestor (fronting the south) - in all, seven. (The temple of) the regional rulers embraced five such fanes: those of two on the left, and two on the right, and that of his great ancestor - in all, five. Grand masters had three fanes: one on the left, one on the right, and that of his great ancestor - in all, three. Servicemen had (only) one. The common people presented their offerings in their (principal) apartment. |

Translation by Legge (1885), slightly changed. |

Even if there are some attempts at reconstruction of such an arrangement, the real shape remains unclear, for instance, if the "fanes" of the two wings were facing each other or placed in the same direction as the fane of the High Ancestor, or whether each fane included a "hall" (gong 宮) and a "sleeping chamber" (qin 寢). There might have been separate buildings in the original shape, but Emperor Ming 漢明帝 (r. 57-75 CE) of the Later Han 後漢 (25-220 CE) decided not to arrange for a temple for himself, but ordered to venerate his soul in the temple of his father (Li 2016a: 35, FN3).

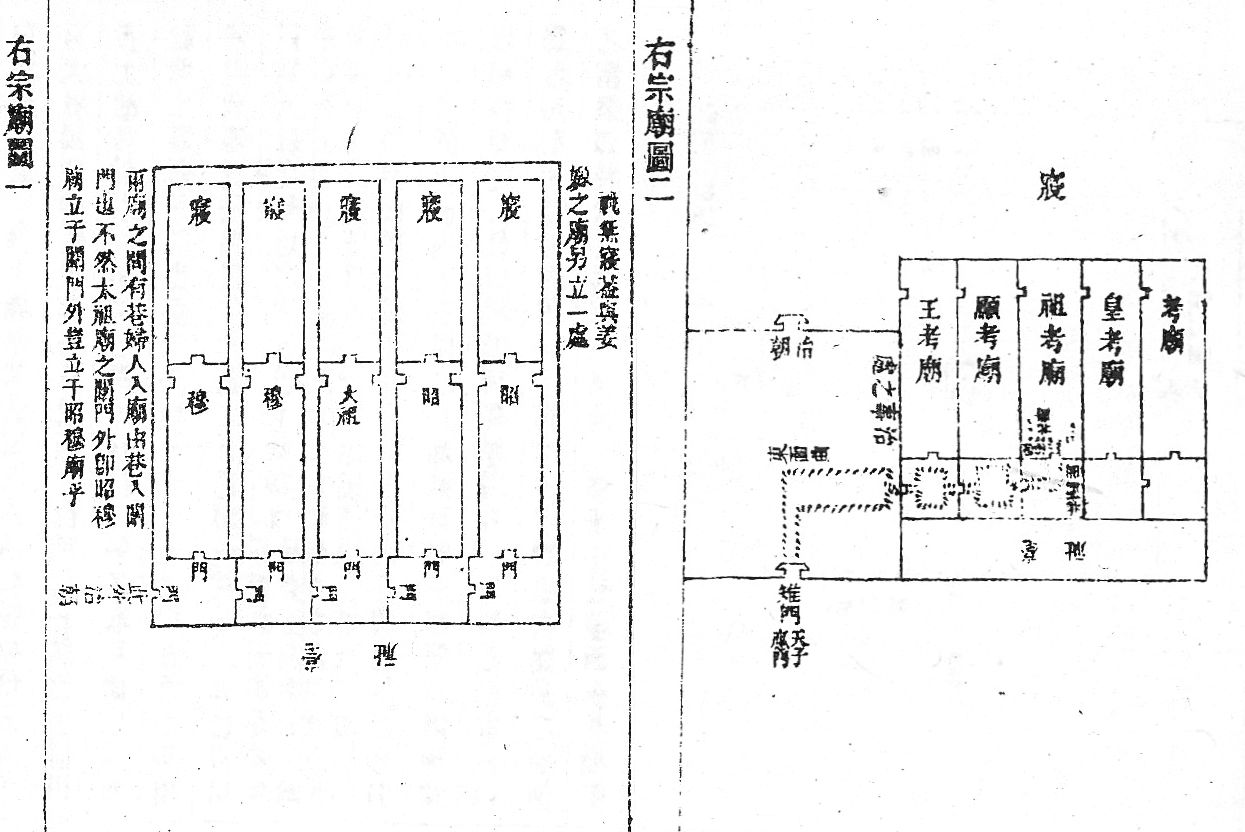

Figure 1. Reconstruction of an ancestral hall

|

Reconstruction of the Zhou ancestral temple by Jiao Xun 焦循 (1763-1820), from Qunjing gongshi tu 群經宮室圖. Click to enlarge. |

The sense behind the zhao-mu system is explained in the Liji 禮記 (ch. Jitong 祭統):

Quotation 2. The zhao-mu system during sacrifices

| 夫祭有昭穆,昭穆者,所以别父子、遠近、長幼、親疏之序而無亂也。是故,有事于大廟,則群昭群穆咸在而不失其倫。此之謂新疏之殺也。 |

At the sacrifice the parties taking part in it were arranged on the left and right, according to their order of descent from the common ancestor, and thus the distinction was maintained between the order of fathers and sons, the near and the distant, the older and the younger, the more nearly related and the more distantly, and there, was no confusion. Therefore at the services in the grand ancestral temple, all in the two lines of descent were present, and no one failed to receive his proper place in their common relationship. This was what was called (showing) the distance gradually increasing between relatives. |

Translation by Legge (1885). |

From this description it can be seen that zhao-mu was an alternating system (fu zi yi qi hao xu 父子易其號序; Yan Shigu's 顏師古 commentary on the Hanshu 漢書) to discern generations: If the father has the position zhao, the son has the position mu, and the grandson again the position zhao (fu zhao zi mu, sun fu wei zhao 父昭子穆,孫復為昭). Yan Shigu further explains the term zhao 昭 as "brilliant" (ming 明), and mu 穆 as "beautiful" (mei 美), yet in fact, the meaning of the two words does not play a role.

The system was used to clarify the generational position of persons related to the royal house, like Kang Shu 康叔, who was "zhao to King Wen" (Wen zhi zhao ye 文之昭也), meaning that he was a generation younger than King Wen.

From the Tang period 唐 (618-907) on scholars became aware that the system was also used to designate older and younger brothers. Bai (1997) even goes so far to say that the system was originally used to rank brothers before it was applied to the ranking of generations. It was revived during the Warring States period 戰國 (5th cent.-221 BCE) in the shape of the "older brother system" (dizhang zhi 嫡長制), according to which the oldest son of the primary consort inherited all rights of his father. These inheritance rights are actually older and date likewise from the Western Zhou period in the shape of the lineage system (zongfa 宗法), according to which the oldest son or heir of his father, established a "great lineage" (dazong 大宗), while his younger brothers were just founders of "small lineages" (xiaozong 小宗) (Li 2016a).

It seems that the zhao-mu system remained mainly for the arrangement of tombs and fanes or spirit tablets in ancestral temples. It originated in the sphere of burials, and its use in ancestral temples was only an adaption as a convenient mode of transferring the sacrifices from the tomb sites to a temple complex close to the living spaces (Li 2016a).

The book Xunzi 荀子 (ch. Wangzhi 王制) sees the zhao-mu system as the most basic distinctions if the borders of social classes are not yet fixed (fen wei ding ye, ze you zhao-mu ye 分未定也,則有昭繆[=穆]也). The zhao-mu ranking was apparently not perceived as a comprehensive system, but rather as a fundamental mode of ranking the status of individuals.

To date none of the ancestral temples of the Zhou dynasty have been found, neither any tomb of a Zhou king. Yet it is possible to demonstrate the application of the zhao-mu system in burials of several of the regional rulers.

The ritual Classic Zhouli 周禮 (part Chunguan 春官) explains that the grave maker (zhongren 冢人) divinated about an ideal place for the "public" tombs (gongmu 公墓), and drew a chart, with the former king (xianwang 先王) in the middle and his zhao and mu descendants to the left and right (zhao-mu wei zuoyou 昭穆为左右). The regional rulers should be buried in front of the two zhao-mu wings (zhuhou ju zuoyou yi qian 諸侯居左右以前), and the ministers and grand masters behind them (qing dafu ju hou 卿大夫居後), each with his kinsmen (ge yi qi zu 各以其族). The Han-period commentator Zheng Xuan 鄭玄 (127-200) added the information that zhao was to the left, mu to the right, and the interspace extending in east-west direction (?).

This custom pertained not just to the burials of the elite, but also to that of commoners, as Jia Gongyan's 賈公彥 (mid-7th cent.) commentary on the Zhouli chapter "Grand Master of Cemeteries" (mu dafu 墓大夫) holds.

The practical application of the zhao-mu method is attested in the two rows of tombs around M166 in Zhangjiapo 張家坡 close to the ancient residence or "capital" Feng 酆 west of Xi'an 西安, Shaanxi (1996a), as well as in the tombs of the Marquesses of Jin 晉 in Zhaocun 趙村 near Quwo 曲沃, Shanxi, and that of the state of Guo 虢 in Shangcunling 上村岭 near Sanmenxia 三門峽, Henan. Not all cases perfectly fit with the description in the Zhouli (Gao 2002).

Even if the zhao-mu system was basically a system of tomb arrangement (Wu 2012), it extended to the arrangement of ancestral temples, sacrifices for them, banquets, and weddings (Li 1990). Only spouses of the right generation could be the mates for young men.

The correct order of the zhao-mu system was also respected during banquets and sacrificial rites, for instance, for the ceremony of circulating the wine beaker (lü chou 旅酬). The chief sacrificer (zhuji zhe 主祭者) handed the cup over (ci jue 賜爵) to the assistants (zhuji zhe 助祭者), and the latter to the correct group of participants, as the Liji chapter Dazhuan 大傳 explains.

Quotation 3. The zhao-mu system during banquets

| 上治祖、禰,尊尊也;下治子孫,親親也;旁治昆弟,合族以食,序以昭繆,別

之以禮義,人道竭矣。 |

Thus [the king] regulated the services to be rendered to his father and grandfather before him—giving honour to the most honourable. He regulated the places to be given to his sons and grandsons below him—showing his affection to his kindred. He regulated (also) the observances for the collateral branches of his cousins;-associating all their members in the feasting. He defined their places according to their order of descent; and his every distinction was in harmony with what was proper and right. In this way the procedure of human duty was made complete. |

Translation by Legge (1885). |

The posthumous honorific titles of the Zhou kings Zhao 周昭王 and Mu 周穆王 have nothing to do with the zhao-mu system (Li 1996a). The theory that the zhao-mu system originated in a matriarchal system must be discarded (Guo 1986).

Sources:

Bai Hongjian 白宏建 (1997). "Zhoudai zhao-mu zhidu bian 周代昭穆制度辨", Jinzhng shizhuan xuebao 晉中師專學報, 1997/1: 19-21.

Gao Zhiqun 高智群 (2002). "Cong Jin hou mudi lun Shang-Zhou mudi zhidu de ji ge wenti 從晉侯墓地論商周墓地制度的幾個問題", Shilin 史林, 2002/1: 1-7.

Guo Zhengkai 郭政凱 (1986). "Lun zhao-mu zhidu de qiyuan ji yanxu 論昭穆制度的起源及延續", Shaanxi shifan xue xuan xuebao (Zhexue shehui kexue ban) 陝西師範大學學報(哲學社會科學版), 1986/1: 77-85.

Li Hengmei 李衡眉 (1990). "Zhao-mu zhidu yu Zhouren zaoqi hunyin xingshi 昭穆制度與周人早期婚姻形式", Lishi yanjiu 歷史研究, 1990/2: 12-25.

Li Hengmei 李衡眉 (1996). Zhao-mu zhidu yanjiu 昭穆制度研究 (Beijing: Qi-Lu shushe).

Li Hengmei 李衡眉 (1996a). "Zhao-mu zhidu yu zongfa zhidu guanxi lunlüe 昭穆制度與宗法制度關係倫略", Lishi yanjiu 歷史研究, 1996/2: 26-36.

Wu Guangxue 武光雪 (2012). "Zhoudai zhao-mu zhidu xintan: Yi Zhoudai sangzang wei guanchadian 周代昭穆制度新探——以周代喪葬為觀察點", Yuncheng xueyuan xuebao 運城學院學報, 2012/6: 56-59.