Feb 24, 2019 © Ulrich Theobald

The lineage system (zongfa 宗法) served in ancient China to discern different lineages of a family cluster, and to rank them with respect to a common ancestor. The system is commonly believed to originate in the Western Zhou period 西周 (11th cent.-770 BCE), yet there might have been precursors of it during the Shang period 商 (17th-11th cent. BCE) which discerned between a primary lineage and lateral lineages, as can be seen in expressions like dazong 大宗 "grand lineage (head)", xiaozong 小宗 "lesser lineage (head)", Yin min liu zu 殷民六族, or Yin min qi zu 殷民七族 "the six/seven lineages of the Yin/Shang".

The Zhou-period lineage system is described in detail in the ritual Classics Yili 儀禮 and Liji 禮記, mainy the latter's chapters Dazhuan 大傳 and Sangfu xiaoji 喪服小記. Yet references to the lineage system can be found in other texts as well, for instance, the ode Ban 板 in the Shijing 詩經 "Book of Songs", where it is said that "great families are buttresses [for the royal house]" (dazong wei han 大宗維翰), and "the king's younger relatives are like a wall" (zong zi wei cheng 宗子維城).

The lineage system of the Zhou, be it that of the Son of Heaven or that of the regional rulers, stipulated that the oldest son (or the son of the primary consort, di 嫡, dizhangzi 嫡長子) succeeded his father, establishing a "grand lineage" (dazong 大宗, zongzi 宗子, "son of the [main] lineage"), while his younger brothers (biezi 別子 "the separate sons", zhizi 支子 "sons of the sideline", shu 庶, shuzi 庶子) venerated the same ancestor, but founded "lesser lineages" (xiaozong 小宗). Members of the family cluster (zongzu 宗族) were discerned by a different surname (shi 氏, like an office or a place name, or different characters used to discern the generations, beifen 輩份), while their family name was the same (Ji 姬 in case of the Zhou dynasty). An alternative mode of distinguishing generations or social ranks of brothers was the zhao-mu system 昭穆.

The earliest study of the ancient lineage system is Cheng Yaotian's 程瑤田 (1725-1814) Zongfa xiaoji 宗法小記.

Quotation 1. Description of the zongfa system 宗法 in the Liji 禮記, ch. Dazhuan 大傳

| 庶子不祭,明其宗也。庶子不得為長子三年,不繼祖也。 |

Any son but the eldest, did not sacrifice to his grandfather, to show there was the Honoured Head (who should do so). Nor could he wear mourning for his eldest son for three years, because he was not the continuator of his grandfather. |

| 別子為祖,繼別為宗,繼禰者為小宗。 |

When any other son but the eldest became an ancestor of a line, he who succeeded him became the Honoured Head (of the branch); and his successor again became the smaller Head. |

| 有百世不遷之宗,有五世則遷之宗。百世不遷者,別子之後也。 |

There was the (great) Honoured Head whose tablet was not removed for a hundred generations. There were the (smaller) Honoured Heads whose tablets were removed after five generations. He whose tablet was not removed for a hundred generations was the successor and representative of the other than the eldest son (who became an ancestor of a line); |

| 宗其繼別子者,百世不遷者也;宗其繼高祖者,五世則遷者也。尊祖故敬宗。敬宗,尊祖之义也。 |

and he was so honoured (by the members of his line) because he continued the (High) ancestor from whom (both) he and they sprang; this was why his tablet was not removed for a hundred generations. He who honoured the continuator of the High ancestor was he whose tablet was removed after five generations. They honoured the Ancestor, and therefore they reverenced the Head. The reverence showed the significance of that honour. |

| 有小宗而無大宗者,有大宗而無小宗者,有無宗亦莫之宗者,公子是也。公子有宗道:公子之公,為其士大夫之庶者宗其士大夫之適者,公子之宗道也。 |

There might be cases in which there was a smaller Honoured Head, and no Greater Head (of a branch family); cases in which there was a Greater Honoured Head, and no smaller Head; and cases in which there was an Honoured Head, with none to honour him. All these might exist in the instance of the son of the ruler of a state. The course to be adopted for the headship of such a son was this; that the ruler, himself the proper representative of former rulers, should for all his half-brothers who were officers and Great officers appoint a full brother, also an officer or a Great officer, to be the Honoured Head. Such was the regular course. |

Translation according to Legge 1885. |

The members and heads of the grand lineage had the right and obligation to "manage" all male persons of the lateral lineages. For this reason, a common saying called this type of large family cluster "a house that will not break apart in a hundred generations" (bai shi bu qian zhi zong 百世不遷之宗). Members of the lesser or lateral lineages had to obey the head of the grand lineage, but were also subject to the elder members of their own lineage. The word zong refers to the lineage as well as to its present head.

The Duke of Zhou 周公旦, for instance, was a younger son of King Wen 周文王, while the oldest son of the primary consort, King Wu 周武王, inherited the throne. The Duke of Zhou's son, Bo Qin 伯禽, was invested as regional ruler of the secondary state of Lu 魯, and was thus the High Ancestor (shizu 始祖, taizu 太祖) of the dukes of Lu. Even if being a lesser lineage head (xiaozong) from the perspective of the king of Zhou, he was the major lineage head (dazong) of the dukes of Zhou.

A younger son of a regional ruler, say, a duke (gongzi 公子 "ducal son"), had not the right to "succeed in the paternal temple" (xu mi 繼禰) and even to venerate his father as an ancestor, but had to establish a lineage of its own (as biezi 別子; xiaozong from the viewpoint of his older brother, but dazong from the viewpoint of his own offspring). The oldest son of the new lineage founder would then "succeed in the respective paternal temple", and this mode would last for "a hundred generations". The younger sons of this lateral lineage (gongsun 公孫 "ducal grandsons") had not the right to succeed in the lineage, but were allowed to venerate their father as the common lineage ancestor (dazong). While each of the younger sons of the following generations was a lesser lineage head (xiaozong), the person of first generation opening a "separated line" (biezi) was the major lineage head (dazong) of his descendants, and was venerated in their ancestral shrines as grandfather (zu 祖), great-grandfather (zengzu 曾祖), and great-great-grandfather (gaozu 高祖), but the fifth generation after him became commoners (shuren 庶人), in the words of the Sangfu xiaoji, there was a shift downward of the head of lesser lineages (qian zong 遷宗).

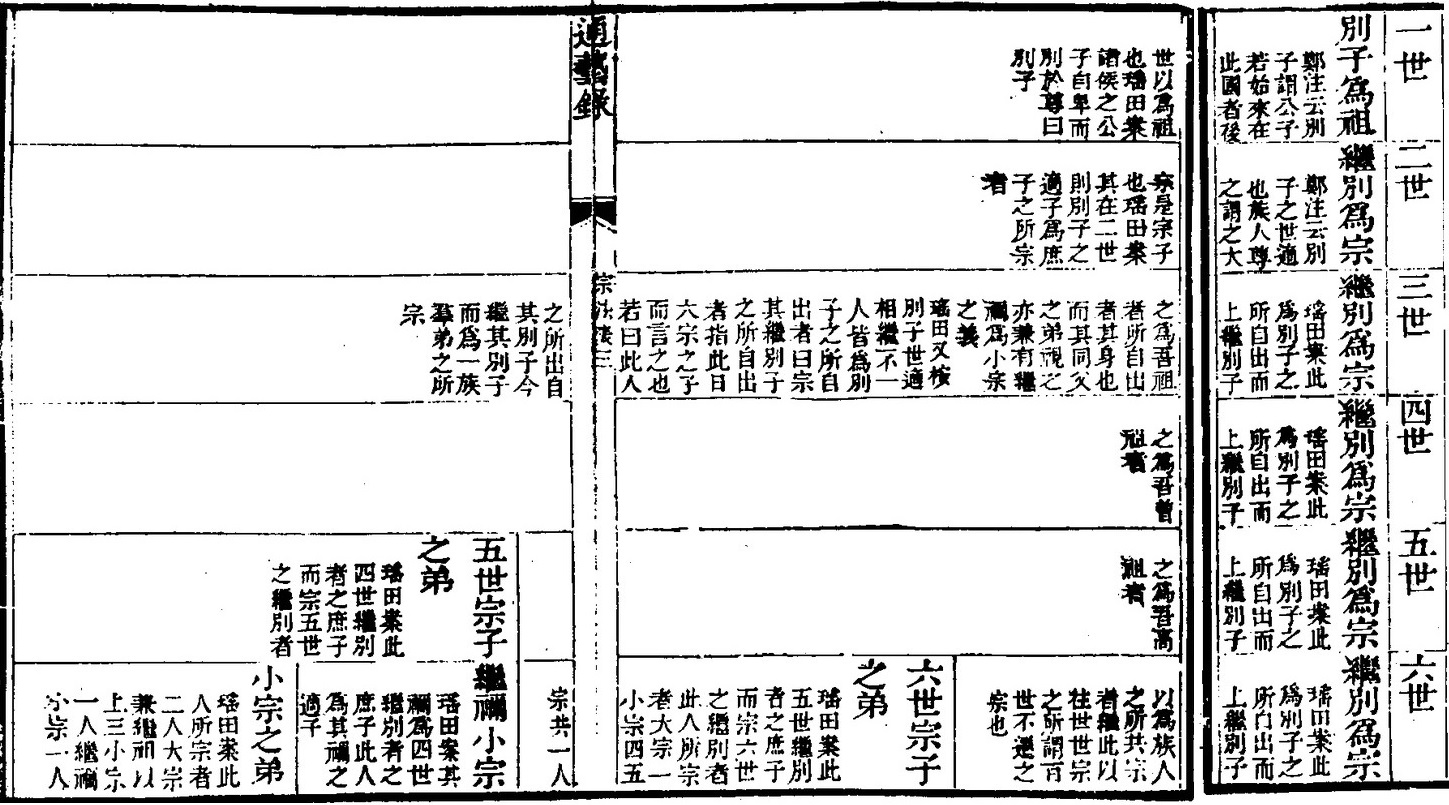

Figure 1. Beginning of Cheng Yaotian's 程瑤田 "Ancestral Lineage Chart" (Zongfabiao 宗法表)

|

The chart shows six generations, beginning with the ancestor (zu 祖), being a "separate [younger] son" (biezi 別子) of a duke (gongzi 公子). He was in a minor position (bei 卑) than his older brother (the father duke's successor), who held a higher position (zun 尊). The separate son's oldest son (a ducal grandson, gongsun 公孫) succeeded his father and founded a new lineage as a major lineage head (dazong 大宗), ruling over all other sons. From Zongfa xiaoji 宗法小記 (Xuxiu siku quanshu 續修四庫全書 edition). Click to enlarge. |

The symbol of the power of the grand lineage head was the maintenance of an ancestral temple (zongmiao 宗廟) for the whole lineage cluster, while the heads of the lesser lineages had temples of their own. All sacrifices in the temples had to be supervised by the lineage heads. Apart from sacrifices to the ancestors, the lineage heads regulated many aspects of daily life, for instance, the capping rites (guanli 冠禮) celebrating the becoming of manhood of a young boy, weddings (hunli 婚禮), covenants between lineage members (mengshi 盟誓), or the celebration of higher birthdays. All these events took place in the ancestral temples, which therefore can be seen as a symbol for the coherence of the whole family cluster.

The lineage head, who more or less symbolized the High Ancestor of the whole lineage cluster, had the last word in all decisions, and even had superiority over family members being wealthy or having achieved high positions in the officialdom. He could direct, penalize, and grant protection (bihu 庇護). When he died, lineage members had to wear sackcloth for three months (qi cui san yue 齊衰[=縗]三月).

During the Zhou period, a lineage head even disposed of armed forces consisting of lineage members. This small "army" could be used as auxiliary unit supporting the royal troops (see Zhou military). During the battle of Yanling 鄢陵 in 575 BCE between the regional states of Chu 楚 and Jin 晉, the latter was supported by the armies of the houses of Luan 欒, Fan 范, Zhonghang 中行, and Xi 郤, all of them being lateral lineages of the ducal house of Jin. Alternatively, a regional ruler (being the head of the grand lineage) could order lateral houses to punish one of them, like in the state of Song 宋, where Duke Wen 宋文公 (r. 610-589) ordered the houses of Dai 戴, Zhuang 莊, and Huan 桓 to punish the lateral lineage of Wu 武.

The jurisdictional power of the head of the grand lineage can be see in the case of Zhao Yang 趙鞅 (Zhao Jianzi 趙簡子), who forced Zhao Wu 趙午 to cede 500 families (and the revenue from their households), and later killed him because of "negligence". Zhi Ying 知罃 (Xun Ying 荀罃), being captured by the army of Chu and set free after having paid a ransom, expressed his willingness to receive punishment for his military failure. Zhao Ying 趙嬰 was once exiled to Qi 齊 because of illicit relationships with a married woman.

When executing punishment, regional rulers used to ask for confirmation by a lineage head, as can be seen in the case of You Chu 游楚, whose sending into exile was first to be reconfirmed by Da Shu 大叔, the head of his lineage. The lineage heads could thus be used by the state to perform administrative and jurisdictional functions. One consequence of this constellation was that lineage members paid sometimes greater loyalty to their "family" than to the state or its representative, the duke.

The households of lineage heads were of considerable size and had to be managed by stewards (shilao 室老, zonglao 宗老, zongren 宗人), who oversaw all matters of the household and the estates of the family. They were heads of a staff including caretakers for the household (jiazai 家宰) and the estates (yizai 邑宰), and managers for land and revenue (situ 司徒), horses and arms (sima 司馬) or such for construction work (gongshi 工師).

The autonomy of lineages ended where the state began. As most members of lateral lineages took over state offices as ministers (qing 卿), grand masters (dafu 大夫), or servicemen (shi 士), they were tied to the grand lineage by two means, namely the genealogical one, and the political one, and of those two, the latter had a greater weight. Nonetheless, certain state ceremonies (banquets, covenants, funerals) required that members of closer lineages had ceremonial preference over those of distant lineages. At least in theory, the Son of Heaven was the head of the grand lineage, and the regional rulers those of lateral lineages.

A common image is that the oldest son of the primary consort of the king of Zhou succeded to him, while younger sons were made regional rulers. The oldest sons of them succeeded as regional rulers, while younger sons were made ministers or grand masters. The oldest sons of them inherited the office of minister or grand master, while their younger sons were made servicemen, and the younger sons of the generation below had the fate of being made commoners (Zhou et al. 1998). Yet this image is not correct. In practice, the system was applied to the descendants of regional rulers who were in the administration of the regional states appointed grand masters and servicemen. Even if many of the early regional rulers were indeed sons and descendants of the kings of Zhou, the zongfa system did not apply to the king or the regional rulers, as there was a difference between the succession of rule (juntong 君統) and that of ancestral veneration (zongtong 宗統), and a matter of political rights (zhengquan 政權) vs. lineage rights (zuquan 族權) (Jin 1956: 205).

The importance of the lineages of the nobility declined during the Warring States period 戰國 (5th cent.-221 BCE), but basic patterns remained and were gradually adopted by the common people.

Sources:

Li Bingzhong 李秉忠, Wei Canlin 衛燦金, Lin Conglong 林從龍, ed. (1990). Jianming wenshi zhishi cidian 簡明文史知識詞典 (Xi'an: Shaanxi renmin chubanshe), 98, 222.

Jia Chongji 賈崇吉, Yang Zhiwu 楊致武, ed. (1992). Zhonghua lunli daode cidian 中華倫理道德辭典 (Xi'an: Shaanxi renmin chubanshe), 342.

Jiang Xijin 蔣錫金, ed. (1990). Wen-shi-zhe xuexi cidian 文史哲學習辭典 (Changchun: Jilin wenshi chubanshe), 419.

Jin Jingfang 金景芳 (1956). "Lun zongfa zhidu 論宗法制度", Dongbei renmin daxue renwen kexue xuebao 東北人民大學人文科學學報, 1956/2: 203-222.

Peng Jinghua 彭景華 (1997). "Zongfa zhi 宗法制", in Men Kui 門巋, Zhang Yanjin 張燕瑾, ed. Zhonghua guocui da cidian 中華國粹大辭典 (Xianggang: Guoji wenhua chuban gongsi), 41.

Wang Songling 王松齡, ed. (1991). Shiyong Zhongguo lishi zhishi cidian 實用中國歷史知識辭典 (Changchun: Jilin wenshi chubanshe), 259.

Wu Shuchen 武樹臣, ed. (1996). Zhongguo chuantong falü wenhua cidian 中國傳統法律文化辭典 (Beijing: Beijing daxue chubanshe), 396.

Xie Weiyang 謝維揚 (1992). "Zongfa 宗法", in Zhongguo da baike quanshu 中國大百科全書, Zhongguo lishi 中國歷史 (Beijing/Shanghai: Zhongguo da baike quanshu chubanshe), Vol. 3, 1621.

Xu Xinghai 徐興海, Liu Jianli 劉建麗, ed. (2000). Rujia wenhua cidian 儒家文化辭典 (Zhengzhou: Zhongzhou guji chubanshe), 326.

Zang Zhen 臧振 (1988). "Zongfa 宗法", in Zhao Jihui 趙吉惠, Guo Hou'an 郭厚安, ed. Zhongguo ruxue cidian 中國儒學辭典 (Shenyang: Liaoning renmin chubanshe), 748.

Zhongguo baike da cidian bianweihui 《中國百科大辭典》編委會, ed. (1990). Zhongguo baike da cidian 中國百科大辭典 (Beijing: Huaxia chubanshe), 634.

Zhou Fazeng 周發增, Chen Longtao 陳隆濤, Qi Jixiang 齊吉祥, ed. (1998). Zhongguo gudai zhengzhi zhidu shi cidian 中國古代政治制度史辭典 (Beijing: Shoudu shifan daxue chubanshe),71.