Ofuda

|

| Votive talismans designed for the home |

|---|

| Ofuda, and Jingū taima when from Ise Jingu |

| Votive paper slips applied to the gates of shrines |

| Senjafuda |

| Amulets sold at shrines for luck and protection |

| Omamori |

| Wooden plaques representing prayers and wishes |

| Ema |

| Paper fortunes received by making a small offering |

| O-mikuji |

| Stamps collected at shrines |

| Shuin |

In Shinto and Buddhism in Japan, an ofuda (お

Certain kinds of ofuda are intended for a specific purpose (such as protection against calamity or misfortune, safety within the home, or finding love) and may be kept on one's person or placed on other areas of the home (such as gates, doorways, kitchens, or ceilings). Paper ofuda may also be referred to as kamifuda (

A specific type of ofuda is a talisman issued by a Shinto shrine on which is written the name of the shrine or its enshrined kami and stamped with the shrine's seal. Such ofuda, also called shinsatsu (

In a similar vein, Buddhist ofuda are regarded as imbued with the spirit and the virtue of buddhas, bodhisattvas, or other revered figures of the Buddhist pantheon, essentially functioning in many cases as a more economic alternative to Buddhist icons and statuary.

History

[edit]

The origins of Shinto and Buddhist ofuda may be traced from both the Taoist lingfu, introduced to Japan via Onmyōdō (which adopted elements of Taoism), and woodblock prints of Buddhist texts and images produced by temples since the Nara and Heian periods.[1][2][3][4][5][6] During the medieval period, the three shrines of Kumano in Wakayama Prefecture stamped their paper talismans on one side with intricate designs of stylized crows and were called Kumano Goōfu (

The shinsatsu currently found in most Shinto shrines meanwhile are modeled after the talisman issued by the Grand Shrines of Ise (Ise Jingū) called Jingū Taima (

In 1871, an imperial decree abolished the oshi and allotted the production and distribution of the amulets, now renamed Jingū Taima, to the shrine's administrative offices.[15] It was around this time that the talisman's most widely known form – a wooden tablet containing a sliver of cedar wood known as gyoshin (

Varieties and usage

[edit]Ofuda come in a variety of forms. Some are slips or sheets of paper, others like the Jingū Taima are thin rectangular plaques (kakubarai/kakuharai (

Ofuda and omamori are available year round in many shrines and temples, especially in larger ones with a permanent staff. As these items are sacred, they are technically not 'bought' but rather 'received' (

-

A Jingū Taima still in its translucent paper wrapper. This cover may be removed when setting up the talisman in a kamidana.[22]

-

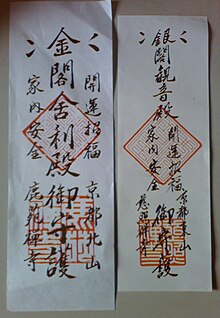

An example of a shinsatsu (from Kōjinyama Shrine in Shiga Prefecture): a plaque with the names of the shrine's kami – Homusubi, Okitsuhiko and Okitsuhime – written in Jindai moji and its paper casing on which is written the name of the shrine or the epithet of its deity – in this case, Kōjinyama-no-Ōkami (

荒神山 大神 , 'Great Deity of Kōjinyama (Shrine)') – and stamped with the seals of the shrine (middle) and its priest (bottom).

Shinto

[edit]Shinsatsu such as Jingū Taima are enshrined in a household altar (kamidana) or a special stand (ofudatate); in the absence of one, they may be placed upright in a clean and tidy space above eye level or attached to a wall. Shinsatsu and the kamidana that house them are set up facing east (where the sun rises), south (the principal direction of sunshine), or southeast.[23][24][25][26]

The Association of Shinto Shrines recommends that a household own at least three kinds of shinsatsu:

- Jingū Taima

- The ofuda of the tutelary deity of one's place of residence (ujigami)

- The ofuda of a shrine one is personally devoted to sūkei jinja (

崇敬 神社 )

In a 'three-door' style (

Other ofuda are placed in other parts of the house. For instance, ofuda of patron deities of the hearth – Sanbō-Kōjin in Buddhism, Kamado-Mihashira-no-Kami (the 'Three Deities of the Hearth': Kagutsuchi, Okitsuhiko and Okitsuhime) in Shinto[33][34] – are placed in the kitchen. In toilets, a talisman of the Buddhist wrathful deity Ucchuṣma (Ususama Myōō), who is believed to purify the unclean, may be installed.[35] Protective gofu such as Tsuno Daishi (

Japanese spirituality lays great importance on purity and pristineness (tokowaka (

-

Various possible ways of arranging ofuda (shinsatsu) in a Shinto altar

-

A place for returning old talismans at Fukagawa Fudō-dō Temple in Tokyo

Gallery

[edit]-

Goōfu from Kumano Hayatama Taisha

-

Kajikimen (

鹿 食 免 , "permit to eat deer"), a talisman issued by Suwa Shrine in Nagano Prefecture. At a time when meat eating was mostly frowned upon due to Buddhist influence, these were held to allow the bearer to eat venison and other meat without incurring impurity or negative karma. -

An ofuda of the tutelary deities of the hearth (kamadogami), for use in kitchens (from Nishino Shrine in Sapporo)

-

Sanjūbanshin]]] Error: {{nihongo3}}: transliteration text not Latin script (pos 7) (help) (

三 十 番 神 , "Thirty Deities", a Shinto-Buddhist grouping of thirty Japanese kami presiding over the thirty days of a lunar month) against disease, from a Nichiren-shū ritual manual -

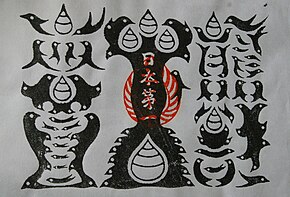

Part of a series of seventy-two talismans (

霊 符 , reifu) (from the Chinese lingfu) known as Taijō Shinsen Chintaku Reifu (太 上 神仙 鎮宅霊 符 , "Talismans of the Most High Gods and Immortals for Home Protection") or simply as Chintaku Reifu (鎮宅霊 符 , "Talismans for Home Protection"). Originally of Daoist origin, these were introduced to Japan during the Middle Ages.[44][45] -

Jingū Taima and other shinsatsu

-

Ofuda posted beside a doorway

-

A sakasafuda (

逆 札 , reverse fuda), a handmade talisman against theft displayed upside-down. This ofuda is inscribed with the date the legendary outlaw Ishikawa Goemon supposedly died: "the 25th day of the 12th month" (十二月 廿 五 日 ).[a][47] Other dates are written in other areas, such as "the 12th day of the 12th month" (十二月 十 二 日 ), which is claimed to be Goemon's birthdate.[46] -

A 'ship shrine' (

艦内 神社 , kannai jinja) inside battleship Mikasa (currently in Mikasa Park in Yokosuka, Kanagawa Prefecture). Beside the altar is a wooden ofuda (kifuda) from Tōgō Shrine (dedicated to the deified naval leader Tōgō Heihachirō, who used Mikasa as his flagship) in Harajuku, Tokyo.

See also

[edit]Explanatory notes

[edit]- ^ The diary of contemporary aristocrat Yamashina Tokitsune seemingly indicates that the historical Goemon was executed on the 24th day of the 8th month (October 8th in the Gregorian calendar).[46]

References

[edit]- ^ Okada, Yoshiyuki. "Shinsatsu, Mamorifuda". Encyclopedia of Shinto. Kokugakuin University. Archived from the original on 2020-10-25. Retrieved 2020-05-23.

- ^ Wen, Benebell (2016). The Tao of Craft: Fu Talismans and Casting Sigils in the Eastern Esoteric Tradition. North Atlantic Books. p. 55. ISBN 978-1623170677.

- ^ Hida, Hirofumi (

火 田 博文 ) (2017).日本人 が知 らない神社 の秘密 (Nihonjin ga shiranai jinja no himitsu). Saizusha. p. 22. Archived from the original on 2022-04-07. Retrieved 2020-05-23. - ^ Mitsuhashi, Takeshi (

三橋 健 ) (2007).神社 の由来 がわかる小 事典 (Jinja no yurai ga wakaru kojiten). PHP Kenkyūsho. p. 115. ISBN 9784569693965. Archived from the original on 2022-05-05. Retrieved 2020-05-23. - ^ Chijiwa, Itaru (

千々 和 到 ) (2010).日本 の護符 文化 (Nihon no gofu bunka). Kōbundō. pp. 33–34. - ^ Machida City Museum of Graphic Arts, ed. (1994).

大和 路 の仏教 版画 ―中世 ・勧進 ・結縁 ・供養 (Yamatoji no bukkyō hanga: chūsei, kanjin, kechien, kuyō). Tokyo Bijutsu. pp. 4–9, 94. ISBN 4-8087-0608-3. - ^ "

熊 野牛 王 神 符 (Kumano Goō Shinpu)". Kumano Hongū Taisha Official Website (in Japanese). Archived from the original on 2020-11-06. Retrieved 2020-05-23. - ^ Kaminishi, Ikumi (2006). Explaining Pictures: Buddhist Propaganda And Etoki Storytelling in Japan. University of Hawaii Press. pp. 138–139. ISBN 9780824826970. Archived from the original on 2022-05-05. Retrieved 2020-05-23.

- ^ Davis, Kat (2019). Japan's Kumano Kodo Pilgrimage: The UNESCO World Heritage trek. Cicerone Press Limited. ISBN 9781783627486. Archived from the original on 2022-05-05. Retrieved 2020-05-23.

- ^ Hardacre, Helen (2017). Shinto: A History. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-062171-1. Archived from the original on 2022-05-05. Retrieved 2020-05-23.

- ^ Shimazu, Norifumi. "Kishōmon". Encyclopedia of Shinto. Kokugakuin University. Archived from the original on 2020-08-05. Retrieved 2020-05-23.

- ^ Oyler, Elizabeth (2006). Swords, Oaths, And Prophetic Visions: Authoring Warrior Rule in Medieval Japan. University of Hawaii Press. pp. 69–70. ISBN 9780824829223. Archived from the original on 2022-05-05. Retrieved 2020-05-23.

- ^ Grapard, Allan G. (2016). Mountain Mandalas: Shugendo in Kyushu. Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 171–172. ISBN 9781474249010. Archived from the original on 2022-05-05. Retrieved 2020-10-03.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Breen, John (2010). "Resurrecting the Sacred Land of Japan: The State of Shinto in the Twenty-First Century" (PDF). Japanese Journal of Religious Studies. 37 (2). Nanzan Institute for Religion and Culture: 295–315. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-05-05. Retrieved 2020-05-23.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Nakanishi, Masayuki. "Jingū taima". Encyclopedia of Shinto. Kokugakuin University. Archived from the original on 2020-09-22. Retrieved 2020-05-23.

- ^ "

神宮 大麻 と神宮 暦 (Jingū taima to Jingu-reki)". Ise Jingu Official Website (in Japanese). Archived from the original on 2020-10-10. Retrieved 2020-05-23. - ^ "

第 14章 神宮 大麻 ・暦 ". Fukushima Jinjachō Official Website (in Japanese). Fukushima Jinjachō. Archived from the original on 2018-06-15. Retrieved 2020-05-23. - ^ "

三 重 )伊勢神宮 で「大麻 用材 伐 始 祭 」". Asahi Shimbun Digital. 15 April 2020. Archived from the original on 2020-04-27. Retrieved 2020-05-23. - ^ "お

神 札 ". Ise Jingū Official Website. Archived from the original on 2020-10-31. Retrieved 2020-05-23. - ^ "

教 えてお伊勢 さん (Oshiete O-Isesan)". Ise Jingū Official Website. Archived from the original on 2020-01-03. Retrieved 2020-05-23. - ^ Jump up to: a b "お

神 札 、お守 りについて (Ofuda, omamori ni tsuite)". Association of Shinto Shrines (Jinja Honchō). Archived from the original on 2020-05-20. Retrieved 2020-05-23. - ^ "「

天 照 皇 大神宮 」のお札 の薄紙 は取 るの?それとも剥 がさない?薄紙 は包装 紙 って本 当 ?". 28 January 2021. - ^ Jump up to: a b "

神棚 のまつり方 ". Jinja no Hiroba. Archived from the original on 2020-04-28. Retrieved 2020-05-23. - ^ Jump up to: a b c "Household-shrine". Wagokoro. Archived from the original on 2020-07-15. Retrieved 2020-05-23.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "

御 神 札 ・御守 ・撤饌 等 の扱 い方 について".城山 八幡宮 (Shiroyama Hachiman-gū) (in Japanese). Archived from the original on 2019-04-07. Retrieved 2020-05-23. - ^ "お

守 りやお札 の取 り扱 い". ja兵庫 みらい (JA Hyōgo Mirai) (in Japanese). Archived from the original on 2022-07-29. Retrieved 2020-05-23. - ^ "Ofuda (talisman)". Green Shinto. 30 July 2011. Archived from the original on 2020-05-29. Retrieved 2020-05-24.

- ^ "お

神 札 (ふだ)のまつり方 (Ofuda no matsurikata)". Association of Shinto Shrines (Jinja Honchō). Archived from the original on 2020-05-21. Retrieved 2020-05-23. - ^ "お

神 札 ・神棚 について". Tokyo Jinjachō (in Japanese). Archived from the original on 2020-04-27. Retrieved 2020-05-23. - ^ Toyozaki, Yōko (2007). 「

日本 の衣食住 」まるごと事典 (Who Invented Natto?). IBC Publishing. pp. 59–61. ISBN 9784896846409. Archived from the original on 2022-05-05. Retrieved 2020-05-23. - ^ "

神棚 と神 拝 作法 について教 えて下 さい。".武蔵 御嶽 神社 (Musashi Mitake Jinja) (in Japanese). Archived from the original on 2020-09-26. Retrieved 2020-05-24. - ^ "

神棚 の祀 り方 と参拝 方法 ".熊野 ワールド【神 々の宿 る熊野 の榊 】 (in Japanese). Archived from the original on 2019-10-29. Retrieved 2020-05-24. - ^ "

奥津 彦命・奥津 姫 命 のご利益 や特徴 ".日本 の神様 と神社 (in Japanese). Archived from the original on 2021-04-15. Retrieved 2020-05-24. - ^ "

奥津 日子 神 ".神 魔 精 妖名辞典 . Archived from the original on 2020-12-01. Retrieved 2020-05-24. - ^ "

烏 枢 沙 摩 明王 とは". うすさま.net (in Japanese). Archived from the original on 2020-02-19. Retrieved 2020-05-24. - ^ Matsuura, Thersa (2019-11-24). "The Great Horned Master (Tsuno Daishi) (Ep. 43)". Uncanny Japan. Archived from the original on 2022-07-29. Retrieved 2020-05-24.

- ^ Groner, Paul (2002). Ryōgen and Mount Hiei: Japanese Tendai in the Tenth Century. University of Hawaii Press. pp. 297–298. ISBN 9780824822606. Archived from the original on 2022-07-29. Retrieved 2020-05-24.

- ^ Reader, Ian; Tanabe, George J. (1998). Practically Religious: Worldly Benefits and the Common Religion of Japan. University of Hawaii Press. p. 196. ISBN 9780824820909. Archived from the original on 2022-07-29. Retrieved 2020-10-03.

- ^ "

御 神 札 について教 えてください。".武蔵 御嶽 神社 (Musashi Mitake Jinja) (in Japanese). Archived from the original on 2020-12-01. Retrieved 2020-05-23. - ^ "お

守 りの扱 い方 ".由加 山 蓮台寺 (Yugasan Rendai-ji) (in Japanese). Archived from the original on 2018-08-30. Retrieved 2020-05-23. - ^ "

知 っているようで知 らない神社 トリビア②". Jinjya.com. Archived from the original on 2020-09-19. Retrieved 2020-05-23. - ^ "どんど

焼 き".菊名 神社 (Kikuna Jinja) (in Japanese). Archived from the original on 2021-03-03. Retrieved 2020-05-23. - ^ "どんど

焼 き【どんと祭 り】古 いお札 やお守 りの処理 の仕方 ".豆 知識 PRESS (in Japanese). 22 December 2019. Archived from the original on 2020-09-30. Retrieved 2020-05-23. - ^ "

霊験 無比 なる「太 上 秘法 鎮宅霊 符 」".星田 妙見 宮 (Hoshida Myōken-gū) (in Japanese). Archived from the original on 2020-03-25. Retrieved 2020-05-26. - ^

国書刊行会 (Kokusho Hankōkai), ed. (1915).信仰 叢書 (Shinkō-sōsho) (in Japanese).国書刊行会 (Kokusho Hankōkai). pp. 354–363. Archived from the original on 2022-07-29. Retrieved 2020-05-26. - ^ Jump up to: a b "

京 のおまじない「逆 さ札 」と天下 の大 泥棒 ・石川 五右衛門 ". WebLeaf (in Japanese). 2 December 2019. Archived from the original on 2020-08-04. Retrieved 2020-05-25. - ^ "「

十 二 月 廿 五 日 」五右衛門 札 貼 り替 え嘉穂 劇場 ". Mainichi Shimbun (in Japanese). 2017-12-26. Archived from the original on 2022-07-29. Retrieved 2020-05-25.

Further reading

[edit]- Nelson, Andrew N., Japanese-English Character Dictionary, Charles E. Tuttle Company: Publishers, Tokyo, 1999, ISBN 4-8053-0574-6

- Masuda Koh, Kenkyusha's New Japanese-English Dictionary, Kenkyusha Limited, Tokyo, 1991, ISBN 4-7674-2015-6

![A Jingū Taima still in its translucent paper wrapper. This cover may be removed when setting up the talisman in a kamidana.[22]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/15/Jingu_taima_cover.jpg/150px-Jingu_taima_cover.jpg)

![A place for returning old talismans at Fukagawa Fudō-dō Temple [ja] in Tokyo](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/2/2b/Amulet_return_at_Fukagawa_Fudoson.jpg/150px-Amulet_return_at_Fukagawa_Fudoson.jpg)

![Sanjūbanshin]]] Error: {{nihongo3}}: transliteration text not Latin script (pos 7) (help) (三十番神, "Thirty Deities", a Shinto-Buddhist grouping of thirty Japanese kami presiding over the thirty days of a lunar month) against disease, from a Nichiren-shū ritual manual](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/c/c7/Talisman_Against_Disease.png/149px-Talisman_Against_Disease.png)

![Part of a series of seventy-two talismans (霊符, reifu) (from the Chinese lingfu) known as Taijō Shinsen Chintaku Reifu (太上神仙鎮宅霊符, "Talismans of the Most High Gods and Immortals for Home Protection") or simply as Chintaku Reifu (鎮宅霊符, "Talismans for Home Protection"). Originally of Daoist origin, these were introduced to Japan during the Middle Ages.[44][45]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/c/c4/Chintaku_Reifu_%28%E9%8E%AE%E5%AE%85%E9%9C%8A%E7%AC%A6%29.png/126px-Chintaku_Reifu_%28%E9%8E%AE%E5%AE%85%E9%9C%8A%E7%AC%A6%29.png)

![A sakasafuda (逆札, reverse fuda), a handmade talisman against theft displayed upside-down. This ofuda is inscribed with the date the legendary outlaw Ishikawa Goemon supposedly died: "the 25th day of the 12th month" (十二月廿五日).[a][47] Other dates are written in other areas, such as "the 12th day of the 12th month" (十二月十二日), which is claimed to be Goemon's birthdate.[46]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/54/Ofuda_jyuni_gatsu_nijyugo_nichi.JPG/200px-Ofuda_jyuni_gatsu_nijyugo_nichi.JPG)