Man'yōgana (

| Man'yōgana | |

|---|---|

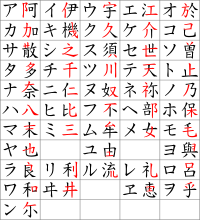

Katakana characters and the man'yōgana they originated from | |

| Script type | |

Time period | c. 650 CE to Meiji era |

| Direction | Top-to-bottom |

| Languages | Japanese and Okinawan |

| Related scripts | |

Parent systems | |

Child systems | Hiragana, Katakana |

Sister systems | Contemporary kanji |

This article needs additional citations for verification. (November 2022) |

Texts using the system also often use Chinese characters for their meaning, but man'yōgana refers to such characters only when they are used to represent a phonetic value. The values were derived from the contemporary Chinese pronunciation, but native Japanese readings of the character were also sometimes used. For example,

Simplified versions of man'yōgana eventually gave rise to both the hiragana and katakana scripts, which are used in Modern Japanese.[2]

Origin

editScholars from the Korean kingdom of Baekje are believed to have introduced the man'yōgana writing system to the Japanese archipelago. The chronicles Kojiki and the Nihon shoki both state so; though direct evidence is hard to come by, scholars tend to accept the idea.[3]

A possible oldest example of man'yōgana is the iron Inariyama Sword, which was excavated at the Inariyama Kofun in 1968. In 1978, X-ray analysis revealed a gold-inlaid inscription consisting of at least 115 Chinese characters, and this text, written in Chinese, included Japanese personal names, which were written for names in a phonetic language. This sword is thought to have been made in the year

There is a strong possibility that the inscription of the Inariyama Sword may be written in a version of the Chinese language used in Baekje.[5]

Principles

editMan'yōgana uses kanji characters for their phonetic rather than semantic qualities. In other words, kanji are used for their sounds, not their meanings. There was no standard system for choice of kanji, and different ones could be used to represent the same sound, with the choice made on the whims of the writer. By the end of the 8th century, 970 kanji were in use to represent the 90 morae of Japanese.[6] For example, the Man'yōshū poem 17/4025 was written as follows:

| Man'yōgana | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Katakana | シオジカラ | タダコエクレバ | ハクヒノウミ | アサナギシタリ | フネカジモガモ |

| Modern | ただ |

||||

| Romanized | Shioji kara | tadakoe kureba | Hakuhi no umi | asanagi shitari | funekaji mogamo |

In the poem, the sounds mo (

In some cases, specific syllables in particular words are consistently represented by specific characters. That usage is known as Jōdai Tokushu Kanazukai and usage has led historical linguists to conclude that certain disparate sounds in Old Japanese, consistently represented by differing sets of man'yōgana characters, may have merged since then.

Types

editIn writing which utilizes man'yōgana, kanji are mapped to sounds in a number of different ways, some of which are straightforward and others which are less so.

Shakuon kana (

| Morae | 1 character, complete | 1 character, partial |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 以 (い) |

|

| 2 | ||

Shakkun kana (

| Morae | 1 character, complete | 1 character, partial | 2 characters | 3 characters |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ||||

| 2 | ||||

| 3 | 慍 (いかり) 炊 (かしき) |

|||

| – | K | S | T | N | P | M | Y | R | W | G | Z | D | B | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | 八方芳房半伴倍泊波婆破薄播幡羽早者速葉歯 | 萬末馬麻摩磨満前真間鬼 | 也移 |

陀太 |

||||||||||

| i1 | 二貳人日仁爾儞邇尼泥耳柔丹荷似煮煎 | 伎祇 |

婢鼻 | |||||||||||

| i2 | 備肥 | |||||||||||||

| u | 宇羽汙于 |

牟武 |

受授 |

|||||||||||

| e1 | 祁家 |

禰尼 |

曳延 |

|||||||||||

| e2 | 閉倍陪拝 |

|||||||||||||

| o1 | 凡方 |

乎呼 |

||||||||||||

| o2 | 乃能 |

其期 |

Development

editDue to the major differences between the Japanese language (which was polysyllabic) and the Chinese language (which was monosyllabic) from which kanji came, man'yōgana proved to be very cumbersome to read and write. As stated earlier, since kanji has two different sets of pronunciation, one based on Sino-Japanese pronunciation and the other on native Japanese pronunciation, it was difficult to determine whether a certain character was used to represent its pronunciation or its meaning, i.e., whether it was man'yōgana or actual kanji, or both.[citation needed]

To alleviate the confusion and to save time writing, kanji that were used as man'yōgana eventually gave rise to hiragana, including the now-obsolete hentaigana (

Man'yōgana continues to appear in some regional names of present-day Japan, especially in Kyūshū.[citation needed][8] A phenomenon similar to man'yōgana, called ateji (

| – | K | S | T | N | H | M | Y | R | W | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | 奈 | 也 | ||||||||||

| ア | カ | サ | タ | ナ | ハ | マ | ヤ | ラ | ワ | |||

| i | ||||||||||||

| イ | キ | シ | チ | ニ | ヒ | ミ | リ | ヰ | ||||

| u | 宇 | 須 | 牟 | |||||||||

| ウ | ク | ス | ツ | ヌ | フ | ム | ユ | ル | ||||

| e | 祢 | |||||||||||

| エ | ケ | セ | テ | ネ | ヘ | メ | レ | ヱ | ||||

| o | 於 | 乃 | 乎 | |||||||||

| オ | コ | ソ | ト | ノ | ホ | モ | ヨ | ロ | ヲ | |||

| – | 尓 | |||||||||||

| ン | ||||||||||||

| – | K | S | T | N | H | M | Y | R | W | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | 奈 | 也 | |||||||||

| あ | か | さ | た | な | は | ま | や | ら | わ | ||

| i | 以 | ||||||||||

| い | き | し | ち | に | ひ | み | り | ゐ | |||

| u | 宇 | ||||||||||

| う | く | す | つ | ぬ | ふ | む | ゆ | る | |||

| e | 祢 | ||||||||||

| え | け | せ | て | ね | へ | め | れ | ゑ | |||

| o | 於 | 乃 | |||||||||

| お | こ | そ | と | の | ほ | も | よ | ろ | を | ||

| – | 无 | ||||||||||

| ん | |||||||||||

See also

edit- Syllabogram

- Sōgana – Archaic Japanese syllabary

- Idu script, Korean analogue

References

editCitations

edit- ^ Bjarke Frellesvig (29 July 2010). A History of the Japanese Language. Cambridge University Press. pp. 14–15. ISBN 978-1-139-48880-8.

- ^ Peter T. Daniels (1996). The World's Writing Systems. Oxford University Press. p. 212. ISBN 978-0-19-507993-7.

- ^ Bentley, John R. (2001). "The origin of man'yōgana". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies. 64 (1): 59–73. doi:10.1017/S0041977X01000040. ISSN 0041-977X. S2CID 162540119.

- ^ Seeley, Christopher (2000). A History of Writing in Japan. University of Hawaii. pp. 19–23. ISBN 9780824822170.

- ^ Farris, William Wayne (1998). Sacred Texts and Buried Treasures: Issues in the Historical Archaeology of Ancient Japan. University of Hawaii Press. p. 99. ISBN 9780824820305.

The writing style of several other inscriptions also betrays Korean influence... Researchers discovered the longest inscription to date, the 115-character engraving on the Inariyama sword, in Saitama in the Kanto, seemingly far away from any Korean emigrés. The style that the author chose for the inscription, however, was highly popular in Paekche.

- ^ Joshi & Aaron 2006, p. 483.

- ^ a b Alex de Voogt; Joachim Friedrich Quack (9 December 2011). The Idea of Writing: Writing Across Borders. BRILL. pp. 170–171. ISBN 978-90-04-21545-0.

- ^ Al Jahan, Nabeel (2017). "The Origin and Development of Hiragana and Katakana". Academia.edu: 8.

Works cited

edit- Joshi, R. Malatesha; Aaron, P. G. (2006). Handbook Of Orthography And Literacy. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-8058-5467-1.

- Bentley, John R. (2001). "The origin of man'yōgana". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies. 64 (1): 59–73. doi:10.1017/S0041977X01000040. JSTOR 3657541. S2CID 162540119.