Susanoo-no-Mikoto

| Susanoo-no-Mikoto | |

|---|---|

God of the sea, storms, and fields. | |

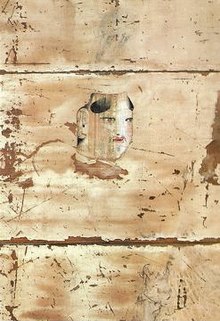

Susanoo slaying Yamata no Orochi, woodblock print by Utagawa Kuniyoshi | |

| Other names |

|

| Japanese | |

| Major cult center | |

| Texts | |

| Genealogy | |

| Parents |

|

| Siblings | |

| Consort |

|

| Children |

|

Susanoo (スサノオ; historical orthography: スサノヲ, 'Susanowo'), often referred to by the honorific title Susanoo-no-Mikoto, is a kami in Japanese mythology. The younger brother of Amaterasu, goddess of the sun and mythical ancestress of the Japanese imperial line, he is a multifaceted deity with contradictory characteristics (both good and bad), being portrayed in various stories either as a wild, impetuous god associated with the sea and storms, as a heroic figure who killed a monstrous serpent, or as a local deity linked with the harvest and agriculture. Syncretic beliefs of the Gion cult that arose after the introduction of Buddhism to Japan also saw Susanoo becoming conflated with deities of pestilence and disease.

Susanoo, alongside Amaterasu and the earthly kami Ōkuninushi (also Ōnamuchi) – depicted as either Susanoo's son or scion depending on the source – is one of the central deities of the imperial Japanese mythological cycle recorded in the Kojiki (c. 712 CE) and the Nihon Shoki (720 CE). One of the gazetteer reports (Fudoki) commissioned by the imperial court during the same period these texts were written, that of Izumo Province (modern Shimane Prefecture) in western Japan, also contains a number of short legends concerning Susanoo or his children, suggesting a connection between the god and this region.

In addition, a few other myths also hint at a connection between Susanoo and the Korean Peninsula.[1]

Name

[edit]Susanoo's name is variously given in the Kojiki as 'Takehaya-Susanoo-no-Mikoto' (

The susa in Susanoo's name has been variously explained as being derived from either of the following words:

- The verb susabu or susamu meaning 'to be impetuous,' 'to be violent,' or 'to go wild'[2][3][4][5]

- The verb susumu, 'to advance'[2]

- The township of Susa (

須佐 郷 ) in Iishi District, Izumo Province (modern Shimane Prefecture)[6] - A word related to the Middle Korean 'susung', meaning 'master' or 'shaman'[7][8][9]

Mythology

[edit]Parentage

[edit]The Kojiki (c. 712 CE) and the Nihon Shoki (720 CE) both agree in their description of Susanoo as the son of the god Izanagi and the younger brother of Amaterasu, the goddess of the sun, and of Tsukuyomi, the god of the moon. The circumstances surrounding the birth of these three deities, collectively known as the "Three Precious Children" (

- In the Kojiki, Amaterasu, Tsukuyomi, and Susanoo came into existence when Izanagi bathed in a river to purify himself after visiting Yomi, the underworld, in a failed attempt to rescue his deceased wife, Izanami. Amaterasu was born when Izanagi washed his left eye, Tsukuyomi was born when he washed his right eye, and Susanoo was born when he washed his nose. Izanagi then appoints Amaterasu to rule Takamagahara (

高天原 , the "Plain of High Heaven"), Tsukuyomi the night, and Susanoo the seas. Susanoo, who missed his mother, kept crying and howling incessantly until his beard grew long, causing the mountains to wither and the rivers to dry up. An angry Izanagi then "expelled him with a divine expulsion."[10][11][12] - The main narrative of the Nihon Shoki has Izanagi and Izanami procreating after creating the Japanese archipelago; to them were born (in the following order) Amaterasu, Tsukuyomi, the 'leech-child' Hiruko, and Susanoo. Amaterasu and Tsukuyomi were sent up to heaven to govern it, while Hiruko – who even at the age of three could not stand upright – was placed on the 'Rock-Camphor Boat of Heaven' (

天 磐 櫲樟船 , Ame-no-Iwakusufune) and set adrift. Susanoo, whose wailing laid waste to the land, was expelled and sent to the netherworld (Ne-no-Kuni).[13] (In the Kojiki, Hiruko is the couple's very first offspring, born before the islands of Japan and the other deities were created; there he is set afloat on a boat of reeds.) - A variant legend recorded in the Shoki has Izanagi begetting Amaterasu by holding a bronze mirror in his left hand, Tsukuyomi by holding another mirror in his right hand, and Susanoo by turning his head and looking sideways. Susanoo is here also said to be banished by Izanagi due to his destructive nature.[14]

- A third variant in the Shoki has Izanagi and Izanami begetting Amaterasu, Tsukuyomi, Hiruko, and Susanoo, as in the main narrative. This version specifies the Rock-Camphor Boat on which Hiruko was placed in to be the couple's fourth offspring. The fifth child, the fire god Kagutsuchi, caused the death of Izanami (as in the Kojiki). As in other versions, Susanoo – who "was of a wicked nature, and was always fond of wailing and wrath" – is here expelled by his parents.[14]

Susanoo and Amaterasu

[edit]

Before Susanoo leaves, he ascends to Takamagahara, wishing to say farewell to his sister Amaterasu. As he did so, the mountains and rivers shook and the land quaked. Amaterasu, suspicious of his motives, went out to meet him dressed in male clothing and clad in armor, but when Susanoo proposed a trial by pledge (ukehi) to prove his sincerity, she accepted. In the ritual, the two gods each chewed and spat out an object carried by the other (in some variants, an item they each possessed).

- Both the Kojiki and the Nihon Shoki's main account relate that Amaterasu broke Susanoo's ten-span sword (

十 拳 剣 /十 握 剣 , totsuka no tsurugi) into three, chewed them and then spat them out. Three goddesses – Takiribime (Tagorihime), Ichikishimahime, and Tagitsuhime – were thus born. Susanoo then took the strings of magatama beads Amaterasu entwined in her hair and round her wrists, likewise chewed the beads and spat them out. Five male deities – Ame-no-Oshihomimi, Ame-no-Hohi, Amatsuhikone, Ikutsuhikone, and Kumano-no-Kusubi – then came into existence.[15][16] - A variant account in the Nihon Shoki has Amaterasu chew three different swords she bore with her – a ten-span sword, a nine-span sword (

九 握 剣 , kokonotsuka no tsurugi), and an eight-span sword (八 握 剣 , yatsuka no tsurugi) – while Susanoo chewed the magatama necklace that hung on his neck.[17] - Another variant account in the Shoki has Susanoo meet a kami named Ha'akarutama (

羽 明 玉 ) on his way to heaven. This deity presented him with the magatama beads used in the ritual. In this version, Amaterasu begets the three goddesses after chewing the magatama beads Susanoo obtained earlier, while Susanoo begets the five gods after biting off the edge of Amaterasu's sword.[18] - A third variant has Amaterasu chewing three different swords to beget the three goddesses as in the first variant. Susanoo, in turn, begat six male deities after chewing the magatama beads on his hair bunches and necklace and spitting them on his hands, forearms, and legs.[19]

Amaterasu declares that the male deities were hers because they were born of her necklace, and that the three goddesses were Susanoo's.[20] Susanoo, announcing that he had won the trial,[a] thus signifying the purity of his intentions, "raged with victory" and proceeded to wreak havoc by destroying his sister's rice fields, defecating in her palace and flaying the 'heavenly piebald horse' (

At this time the eight-hundred myriad deities deliberated together, imposed upon Haya-Susanoo-no-Mikoto a fine of a thousand tables of restitutive gifts, and also, cutting off his beard and the nails of his hands and feet, had him exorcised and expelled him with a divine expulsion.[28]

- A fourth variant of the story in the Shoki reverses the order of the two events. This version relates that Susanoo and Amaterasu each owned three rice fields; Amaterasu's fields were fertile, while Susanoo's were dry and barren. Driven by jealousy, Susanoo ruins his sister's rice fields, causing her to hide in the Ama-no-Iwato and him to be expelled from heaven (as above). During his banishment, Susanoo, wearing a hat and a raincoat made of straw, sought shelter from the heavy rains, but the other gods refused to give him lodging. He then ascends to heaven once more to say farewell to Amaterasu.

After this, Sosa no wo no Mikoto said:—'All the Gods have banished me, and I am now about to depart for ever. Why should I not see my elder sister face to face; and why take it on me of my own accord to depart without more ado?' So he again ascended to Heaven, disturbing Heaven and disturbing Earth. Now Ame no Uzume, seeing this, reported it to the Sun-Goddess. The Sun-Goddess said:—'My younger brother has no good purpose in coming up. It is surely because he wishes to rob me of my kingdom. Though I am a woman, why should I shrink?' So she arrayed herself in martial garb, etc., etc.

Thereupon Sosa no wo no Mikoto swore to her, and said:—'If I have come up again cherishing evil feelings, the children which I shall now produce by chewing jewels will certainly be females, and in that case they must be sent down to the Central Land of Reed-Plains. But if my intentions are pure, then I shall produce male children, and in that case they must be made to rule the Heavens. The same oath will also hold good as to the children produced by my elder sister.'[29]

The two then perform the ukehi ritual; Susanoo produces six male deities from the magatama beads on his hair knots. Declaring that his intentions were indeed pure, Susanoo gives the six gods to Amaterasu's care and departs.[30]

| Kojiki | Nihon Shoki (main text) |

Nihon Shoki (variant 1) |

Nihon Shoki (variant 2) |

Nihon Shoki (variant 3) |

Nihon Shoki (variant 4) |

|---|

Susanoo and Ōgetsuhime

[edit]The Kojiki relates that during his banishment, Susanoo asked the goddess of food, Ōgetsuhime-no-Kami (

Slaying the Yamata no Orochi

[edit]

After his banishment, Susanoo came down from heaven to Ashihara-no-Nakatsukuni (

Sympathizing with their plight, Susanoo hid Kushinadahime by transforming her into a comb (kushi), which he placed in his hair. He then made the serpent drunk on strong sake and then killed it as it lay in a drunken stupor. From within the serpent's tail Susanoo discovered the sword Ame-no-Murakumo-no-Tsurugi (

[Susanoo-no-Mikoto] said to Ashinazuchi and Tenazuchi-no-Kami:

"Distill thick wine of eight-fold brewings; build a fence, and make eight doors in the fence. At each door, tie together eight platforms, and on each of these platforms place a wine barrel. Fill each barrel with the thick wine of eight-fold brewings, and wait."

They made the preparations as he had instructed, and as they waited, the eight-tailed dragon came indeed, as [the old man] had said.

Putting one head into each of the barrels, he drank the wine; then, becoming drunk, he lay down and slept.

Then Haya-Susanoo-no-Mikoto unsheathed the sword ten hands long which he was wearing at his side, and hacked the dragon to pieces, so that the Hi river ran with blood.

When he cut [the dragon's] middle tail, the blade of his sword broke. Thinking this strange, he thrust deeper with the stub of his sword, until a great sharp sword appeared.

He took this sword out and, thinking it an extraordinary thing, reported [the matter] and presented [the sword] to Amaterasu-Ōmikami.

This is the sword Kusa-nagi.[34]

Amaterasu later bequeathed the sword to Ninigi, her grandson by Ame-no-Oshihomimi, along with the mirror Yata no Kagami and the jewel Yasakani no Magatama. This sacred sword, mirror, and jewel collectively became the three Imperial Regalia of Japan.

While most accounts place Susanoo's descent in the headwaters of the river Hi in Izumo (

The ten-span sword Susanoo used to slay the Yamata no Orochi, unnamed in the Kojiki and the Shoki's main text, is variously named in the Shoki's variants as Orochi-no-Aramasa (

Susanoo in Soshimori

[edit]

A variant account in the Shoki relates that after Susanoo was banished due to his bad behavior, he descended from heaven, accompanied by a son named Isotakeru-no-Mikoto (

The palace of Suga

[edit]After slaying the Yamata no Orochi, Susanoo looked for a suitable place in Izumo to live in. Upon arriving at a place called Suga (

Man'yogana (Kojiki):

夜 久 毛 多 都 伊豆 毛 夜 幣 賀 岐都 麻 碁 微 爾 夜 幣 賀 岐都久 流 曾能夜 幣 賀 岐袁

Old Japanese: yakumo1 tatu / idumo1 yape1gaki1 / tumago2mi2 ni / yape1gaki1 tukuru / so2no2 yape1gaki1 wo

Modern Japanese: yakumo tatsu / izumo yaegaki / tsumagomi ni / yaegaki tsukuru / sono yaegaki o

Donald L. Philippi (1968) translates the song into English thus:

The many-fenced palace of IDUMO

Of the many clouds rising—

To dwell there with my spouse

Do I build a many-fenced palace:

Ah, that many-fenced palace![40]

The Kojiki adds that Susanoo appointed Kushinadahime's father Ashinazuchi to be the headman of his new dwelling, bestowing upon him the name Inada-no-Miyanushi-Suga-no-Yatsumimi-no-Kami (

The Shoki's main narrative is roughly similar: Susanoo appoints Ashinazuchi and Tenazuchi to be the keepers of his palace and gives them the title Inada-no-Miyanushi. The child born to Susanoo and Kushiinadahime in this version is identified as Ōnamuchi-no-Kami (

After having thus lived for a time in Izumo, Susanoo at length finally found his way to Ne-no-Kuni.

Planting trees

[edit]One variant in the Shoki has Susanoo pulling out hairs from different parts of his body and turning them into different kinds of trees. Determining the use of each, he then gives them to his three children – Isotakeru-no-Mikoto, Ōyatsuhime-no-Mikoto (

The myth of Susanoo's descent in Soshimori has Isotakeru bringing seeds with him from Takamagahara which he did not choose to plant in Korea but rather spread throughout Japan, beginning with Tsukushi Province. The narrative adds that it is, for this reason, why Isotakeru is styled Isaoshi-no-Kami (

Susanoo and Ōnamuji

[edit]

In the Kojiki, a sixth-generation descendant of Susanoo, Ōnamuji-no-Kami (

- Susanoo, upon inviting Ōnamuji to his dwelling, had him sleep in a chamber filled with snakes. Suseribime aided Ōnamuji by giving him a scarf that repelled the snakes.

- The following night, Susanoo had Ōnamuji sleep in another room full of centipedes and bees. Once again, Suseribime gave Ōnamuji a scarf that kept the insects at bay.

- Susanoo shot an arrow into a large plain and had Ōnamuji fetch it. As Ōnamuji was busy looking for the arrow, Susanoo set the field on fire. A field mouse showed Ōnamuji how to hide from the flames and gave him the arrow he was searching for.

- Susanoo, upon discovering that Ōnamuji had survived, summoned him back to his palace and had him pick the lice and centipedes from his hair. Using a mixture of red clay and nuts given to him by Suseribime, Ōnamuji pretended to chew and spit out the insects he was picking.

After Susanoo was lulled to sleep, Ōnamuji tied Susanoo's hair to the hall's rafters and blocked the door with an enormous boulder. Taking his new wife Suseribime as well as Susanoo's sword, koto, and bow and arrows with him, Ōnamuji thus fled the palace. The koto brushed against a tree as the two were fleeing; the sound awakens Susanoo, who, rising with a start, knocks his palace down around him. Susanoo then pursued them as far as the slopes of Yomotsu Hirasaka (

Susanoo in the Izumo Fudoki

[edit]

The Fudoki of Izumo Province (completed 733 CE) records the following etiological legends which feature Susanoo and his children:

- The township of Yasuki (

安来 郷 ) in Ou District (意宇 郡 ) is named such after Susanoo visited the area and said, "My mind has been comforted (yasuku nari tamau)."[46][47] - The township of Ōkusa (

大草 郷 ) in Ou is said to have been named after a son of Susanoo named Aohata-Sakusahiko-no-Mikoto (青 幡 佐 久佐 比 古 命 ).[48][49] - The township of Yamaguchi (

山口 郷 ) in Shimane District (島根 郡 ) is named as such after another son of Susanoo, Tsurugihiko-no-Mikoto (都留 支 日子 命 ), declared these entrance to the hills (yamaguchi) to be his territory.[50][51] - The township of Katae (

方 結 郷 ) in Shimane received its name after Kunioshiwake-no-Mikoto (国 忍 別命 ), a son of Susanoo, said, "The land I govern is in good condition geographically (kunigatae)."[50][52] - The township of Etomo (

恵曇 郡 ) in Akika District (秋鹿 郡 ) is named such after Susanoo's son Iwasakahiko-no-Mikoto (磐 坂 日子 命 ) noted the area's resemblance to a painted arm guard (画 鞆, etomo).[53][54] - The township of Tada (

多 太 郷 ) in Akika District received its name after Susanoo's son Tsukihoko-Tooruhiko-no-Mikoto (衝杵等 乎留比 古 命 , also Tsukiki-Tooruhiko) came there and said, "My heart has become bright and truthful (tadashi)."[55][56] - The township of Yano (

八野 郷 ) in Kando District (神門 郡 ) is named after Susanoo's daughter Yanowakahime-no-Mikoto (八野 若 日 女 命 ), who lived in the area. Ōnamochi (大穴 持 命 , i.e. Ōkuninushi), also known as Ame-no-Shita-Tsukurashishi-Ōkami (所 造 天下 大神 , 'Great Deity, Maker of All Under Heaven'), who wished to marry her, had a house built at this place.[57][58] - The township of Namesa (

滑 狭 郷 ) in Kando District (神門 郡 ) is named after a smooth stone (滑 磐石 , nameshi iwa) Ame-no-Shita-Tsukurashishi-Ōkami (Ōnamochi) spotted while visiting Susanoo's daughter Wakasuserihime-no-Mikoto (和 加 須世理 比 売 命 , the Kojiki's Suseribime), who is said to have lived there.[59][60] - The township of Susa (

須佐 郷 ) in Iishi District (飯石 郡 ) is said to be named after Susanoo, who enshrined his spirit in this place:[61]

Township of Susa. It is 6.3 miles west of the district office. The god Susanowo said, "Though this land is small, it is good land for me to own. I would rather have my name [associated with this land than] with rocks or trees." After saying this, he left his spirit to stay quiet at this place and established the Great Rice Field of Susa and the Small Rice Field of Susa. That is why it is called Susa. There are tax granaries in this township.[62]

- The township of Sase (

佐 世 郷 ) in Ōhara District (大原 郡 ) is said to have gained its name when Susanoo danced there wearing leaves of a plant called sase on his head.[63][64] - Mount Mimuro (

御 室山 , Mimuro-yama) in the township of Hi (斐伊郷 ) in Ōhara District is said to have been the place where Susanoo built a temporary dwelling (御室 , mimuro, lit. 'noble chamber') in which he stayed the night.[63][65]

Susanoo, Mutō Tenjin and Gozu Tennō

[edit]

The syncretic deity Gozu Tennō (

Gozu Tennō became associated with another deity called Mutō-no-Kami (

The earliest known version of this legend, found in the Fudoki of Bingo Province (modern eastern Hiroshima Prefecture) compiled during the Nara period (preserved in an extract quoted by scholar and Shinto priest Urabe Kanekata in the Shaku Nihongi), has Mutō explicitly identify himself as Susanoo.[73] This suggests that Susanoo and Mutō Tenjin were already conflated in the Nara period, if not earlier. Sources that equate Gozu Tennō with Susanoo only first appear during the Kamakura period (1185–1333), although one theory supposes that these three gods and various other disease-related deities were already loosely coalesced around the 9th century, probably around the year 877 when a major epidemic swept through Japan.[70]

Analysis

[edit]

The image of Susanoo that can be gleaned from various texts is rather complex and contradictory. In the Kojiki and the Shoki he is portrayed first as a petulant young man, then as an unpredictable, violent boor who causes chaos and destruction before turning into a monster-slaying culture hero after descending into the world of men, while in the Izumo Fudoki, he is simply a local god apparently connected with rice fields, with almost none of the traits associated with him in the imperial mythologies being mentioned. Due to his multifaceted nature, various authors have had differing opinions regarding Susanoo's origins and original character.

The Edo period kokugaku scholar Motoori Norinaga, in his Kojiki-den (Commentary on the Kojiki), characterized Susanoo as an evil god in contrast to his elder siblings Amaterasu and Tsukuyomi, as the unclean air of the land of the dead still adhered to Izanagi's nose from which he was born and was not purified completely during Izanagi's ritual ablutions.[74][75] The early 20th century historian Tsuda Sōkichi, who put forward the then-controversial theory that the Kojiki's accounts were not based on history (as Edo period kokugaku and State Shinto ideology believed them to be) but rather propagandistic myths concocted to explain and legitimize the rule of the imperial dynasty, also saw Susanoo as a negative figure, arguing that he was created to serve as the rebellious opposite of the imperial ancestress Amaterasu.[75] Ethnologist Ōbayashi Taryō, speaking from the standpoint of comparative mythology, opined that the stories concerning the three deities were ultimately derived from a continental (Southeast Asian) myth in which the Sun, the Moon and the Dark Star are siblings and the Dark Star plays an antagonistic role (cf. Rahu and Ketu from Hindu religion);[76][77] Ōbayashi thus also interprets Susanoo as a bad hero.[75]

Other scholars, however, take the position that Susanoo was not originally conceived of as a negative deity. Mythologist Matsumura Takeo for instance believed the Izumo Fudoki to more accurately reflect Susanoo's original character: a peaceful, simple kami of the rice fields. In Matsumura's view, Susanoo's character was deliberately reversed when he was grafted into the imperial mythology by the compilers of the Kojiki. Matsumoto Nobuhiro, in a similar vein, interpreted Susanoo as a harvest deity.[78] While the Izumo Fudoki claims that the township of Susa in Izumo is named after its deity Susanoo, it has been proposed that the opposite might have actually been the case and Susanoo was named after the place, with his name being understood in this case as meaning "Man (o) of Susa."[79]

While both Matsumura and Matsumoto preferred to connect Susanoo with rice fields and the harvest, Matsumae Takeshi put forward the theory that Susanoo was originally worshiped as a patron deity of sailors. Unlike other scholars who connect Susanoo with Izumo, Matsumae instead saw Kii Province (the modern prefectures of Wakayama and Mie) as the birthplace of Susanoo worship, pointing out that there was also a settlement in Kii named Susa (

A few myths, such as that of Susanoo's descent in Soshimori in Silla, seem to suggest a connection between the god and the Korean Peninsula. Indeed, some scholars have hypothesized that the deities who were eventually conflated with Susanoo, Mutō Tenjin, and Gozu Tennō, may have had Korean origins as well, with the name 'Mutō' (

Emilia Gadeleva (2000) sees Susanoo's original character as being that of a rain god – more precisely, a god associated with rainmaking – with his association with the harvest and a number of other elements from his myths ultimately springing from his connection with rainwater. He thus serves as a contrast and a parallel to Amaterasu, the goddess of the sun. Gadeleva also acknowledges the foreign elements in the god's character by supposing that rainmaking rituals and concepts were brought to Japan in ancient times from the continent, with the figure of the Korean shaman (susung) who magically controlled the abundance of rain eventually morphing into the Japanese Susanoo, but at the same time stresses that Susanoo is not completely a foreign import but must have had Japanese roots at his core. In Gadeleva's view, while the god certainly underwent drastic changes upon his introduction in the imperial myth cycle, Susanoo's character already bore positive and negative features since the beginning, with both elements stemming from his association with rain. As the right quantity of rainwater was vital for ensuring a rich harvest, calamities caused by too much or too little rainfall (i.e. floods, drought, or epidemics) would have been blamed on the rain god for not doing his job properly. This, according to Gadeleva, underlies the occasional portrayal of Susanoo in a negative light.[84]

Susanoo and Ne-no-Kuni

[edit]In the Kojiki and the Nihon Shoki, Susanoo is repeatedly associated with Ne-no-Kuni (Japanese:

While Matsumura Takeo suggested that Ne-no-Kuni originally referred to the dimly remembered original homeland of the Japanese people,[74] Emilia Gadeleva instead proposes that the two locales, while similar in that both were subterranean realms associated with darkness, differed from each other in that Yomi was associated with death, while Ne-no-Kuni, as implied by the myth about Ōnamuji, was seemingly associated with rebirth. Ne-no-Kuni being a land of revival, as per Gadeleva's theory, is why Susanoo was connected to it: Susanoo, as the god that brought rain and with it, the harvest, was needed in Ne-no-Kuni to secure the rebirth of crops. In time, however, the two locations were confused with each other, so that by the time the Kojiki and the Shoki were written Ne-no-Kuni came to be seen like Yomi as an unclean realm of the dead. Gadeleva argues that this new image of Ne-no-Kuni as a place of evil and impurity contributed to Susanoo becoming more and more associated with calamity and violence.[85]

Susanoo's rampage

[edit]

Susanoo's acts of violence after proving his sincerity in the ukehi ritual has been a source of puzzlement to many scholars. While Edo period authors such as Motoori Norinaga and Hirata Atsutane believed that the order of the events had become confused and suggested altering the narrative sequence so that Susanoo's ravages would come before, and not after, his victory in the ukehi, Donald Philippi criticized such solutions as "untenable from a textual standpoint."[86] (Note that as mentioned above, one of the variants in the Shoki does place Susanoo's ravages and banishment before the performance of the ukehi ritual.)

Tsuda Sōkichi saw a political significance in this story: he interpreted Amaterasu as an emperor-symbol, while Susanoo in his view symbolized the various rebels who (unsuccessfully) rose up against the imperial court.[87]

Emilia Gadeleva observes that Susanoo, at this point in the narrative, is portrayed similarly to the hero Yamato Takeru (Ousu-no-Mikoto), in that both were rough young men possessed with "valor and ferocity" (takeku-araki kokoro); their lack of control over their fierce temperament leads them to commit violent acts. It was therefore imperative to direct their energies elsewhere: Ousu-no-Mikoto was sent by his father, the Emperor Keikō, to lead conquering expeditions, while Susanoo was expelled by the heavenly gods. This ultimately resulted in the two becoming famed as heroic figures.[88]

A prayer or norito originally recited by the priestly Nakatomi clan in the presence of the court during the Great Exorcism (

- Breaking down the ridges

- Covering up the ditches

- Releasing the irrigation sluices

- Double planting

- Setting up stakes

- Skinning alive

- Skinning backward

- Defecation

1, 2, 6, 7 and 8 are committed by Susanoo in the Kojiki, while 3, 4, 5 are attributed to him in the Shoki. In ancient Japanese society, offenses related to agriculture were regarded as abhorrent as those that caused ritual impurity.[91]

One of the offensive acts Susanoo committed during his rampage was 'skinning backward' (

The gods punish Susanoo for his rampages by cutting off his beard, fingernails, and toenails. One textual tradition in which the relevant passage is read as "cutting off his beard and causing the nails of his hands and feet to be extracted" (

Family

[edit]| Susanoo's family tree (based on the Kojiki) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Consorts

[edit]

Susanoo's consorts are:

- Kushinadahime (

櫛 名田 比 売 ), daughter of Ashinazuchi and Tenazuchi, children of Ōyamatsumi, a son of Izanagi and elder brother of Susanoo (Kojiki, Nihon Shoki)

- Also known under the following names:

- Kushiinadahime (

奇 稲田 姫 , Nihon Shoki) - Inadahime (

稲田 媛 , Shoki) - Makami-Furu-Kushiinadahime (

真 髪 触 奇 稲田 媛 , Shoki) - Kushiinada-Mitoyomanurahime-no-Mikoto (

久志 伊奈 太美 等 与 麻 奴 良 比 売 命 , Izumo Fudoki)

- Kushiinadahime (

- Kamuōichihime (

神大 市 比 売 ), another daughter of Ōyamatsumi (Kojiki) - Samirahime-no-Mikoto (

佐美 良 比 売 命 ), a goddess worshiped in Yasaka Shrine reckoned as a consort of Susanoo[103]

Offspring

[edit]Susanoo's child by Kushinadahime is variously identified as Yashimajinumi-no-Kami (

Susanoo's children by Kamuōichihime meanwhile are:

- Ōtoshi-no-Kami (

大年 神 ) - Ukanomitama-no-Kami (宇迦

之 御 魂 神 )

Susanoo's children who are either born without a female partner or whose mother is unidentified are:

- The Munakata goddesses of Munakata Taisha in Munakata, Fukuoka Prefecture

- Takiribime-no-Mikoto (

多紀 理 毘売命 )

- Takiribime-no-Mikoto (

- Also known as Tagorihime (

田 心 姫 )- Ichikishimahime-no-Mikoto (

市 寸 島 比 売 命 )

- Ichikishimahime-no-Mikoto (

- Also known as Okitsushimahime (瀛津

島 姫 )- Tagitsuhime-no-Mikoto (

多岐 都 比 売 命 )

- Tagitsuhime-no-Mikoto (

- Suseribime-no-Mikoto (須勢

理 毘売命 )

- Also known as Wakasuserihime-no-Mikoto (

和 加 須世理 比 売 命 ) in the Izumo Fudoki

- Isotakeru / Itakeru-no-Mikoto (

五十猛 命 ) - Ōyatsuhime-no-Mikoto (

大屋 津 姫 命 ) - Tsumatsuhime-no-Mikoto (枛津

姫 命 )

Deities identified as Susanoo's children found only in the Izumo Fudoki are:

- Kunioshiwake-no-Mikoto (

国 忍 別命 ) - Aohata-Sakusahiko-no-Mikoto (

青 幡 佐草 日 古 命 ) - Iwasakahiko-no-Mikoto (

磐 坂 日子 命 ) - Tsukihoko-Tooruhiko-no-Mikoto (衝桙

等 番 留 比 古 命 ) - Tsurugihiko-no-Mikoto (

都留 支 日子 命 ) - Yanowakahime-no-Mikoto (

八野 若 日 女 命 )

An Edo period text, the Wakan Sansai Zue (

Worship

[edit]| Part of a series on |

| Shinto |

|---|

|

In addition to his connections with the sea and tempests, due to his mythical role as the slayer of the Yamata no Orochi and his historical association with pestilence deities such as Gozu Tennō, Susanoo is also venerated as a god who wards off misfortune and calamity, being invoked especially against illness and disease.[104] As his heroic act helped him win the hand of Kushinadahime, he is also considered to be a patron of love and marriage, such as in Hikawa Shrine in Saitama Prefecture (see below).[105][106]

Shrines

[edit]Susanoo is worshiped in a number of shrines throughout Japan, especially in Shimane Prefecture (the eastern part of which is the historical Izumo Province). A few notable examples are:

- Susa Shrine (

須佐 神社 ) in Izumo, Shimane Prefecture

- Listed in the Izumo Fudoki as one of five shrines in Iishi District that were registered with the Department of Divinities, this shrine is identified as the place in what was formerly the township of Susa where Susanoo chose to enshrine his spirit.[62][107] The shrine was also known as Jūsansho Daimyōjin (

十 三 所 大明神 ) and Susa no Ōmiya (須佐 大宮 'Great Shrine of Susa') during the medieval and early modern periods.[108][109] The shrine's priestly lineage, the Susa (or Inada) clan (須佐 氏 /稲田 氏 ), were considered to be the descendants of Susanoo via his son Yashimashino-no-Mikoto (八島 篠 命 , the Kojiki's Yashimajinumi-no-Kami)[110][111] or Ōkuninushi.[109] Besides Susanoo, his consort Kushinadahime and her parents Ashinazuchi and Tenazuchi are also enshrined here as auxiliary deities.[111][112]

- Suga Shrine (須我

神社 ) in Unnan, Shimane Prefecture

- This shrine, claimed to stand on the site of the palace Susanoo built after defeating the Yamata no Orochi, enshrines Susanoo, Kushinadahime, and their son Suga-no-Yuyamanushi-Minasarohiko-Yashima-no-Mikoto (

清之 湯山 主 三名狭漏彦八島野命, i.e. Yashimajinumi-no-Kami).[113] Listed in the Izumo Fudoki as one of sixteen shrines in Ōhara District not registered with the Department of Divinities.[114]

- Yaegaki Shrine (

八 重 垣 神社 ), in Matsue, Shimane Prefecture

- Dedicated to Susanoo, Kushinadahime, Ōnamuchi (Ōkuninushi) and Aohata-Sakusahiko, the shrine takes its name from the 'eightfold fence' (yaegaki) mentioned in Susanoo's song. The shrine's legend claims that Susanoo hid Kushinadahime in the forest within the shrine's precincts, enclosing her in a fence, when he slew the Yamata no Orochi.[115] Identified with the Sakusa Shrine (

佐久 佐 社 ) mentioned in the Izumo Fudoki.[116][117]

- Kumano Taisha (

熊野 大社 ) in Matsue, Shimane Prefecture

- Reckoned as Izumo Province's ichinomiya alongside Izumo Grand Shrine. Not to be confused with the Kumano Sanzan shrine complex in Wakayama Prefecture. Its deity, known under the name 'Izanagi-no-Himanago Kaburogi Kumano-no-Ōkami Kushimikenu-no-Mikoto' (

伊 邪 那 伎日真名子 加 夫 呂 伎熊野 大神 櫛 御 気 野 命 , "Beloved Child of Izanagi, Divine Ancestor [and] Great Deity of Kumano, Kushimikenu-no-Mikoto'), is identified with Susanoo.[118][119] The shrine is also considered in myth to be where the use of fire originated; two ancient fire-making tools, a hand drill (燧 杵 hikiri-kine) and a hearthboard (燧 臼 hikiri-usu) are kept in the shrine and used in the shrine's Fire Lighting Ceremony (鑚火祭 Kiribi-matsuri or Sanka-sai) held every October.[120][121]

- Susa Shrine (

須佐 神社 ) in Arida, Wakayama Prefecture

Gion shrines

[edit]The following shrines were originally associated with Gozu Tennō:

- Yasaka Shrine (

八坂神社 ) in Gion, Higashiyama, Kyoto, Kyoto Prefecture – Head shrine of the Yasaka shrine network - Tsushima Shrine (

津島 神社 ) in Tsushima, Aichi Prefecture – Head shrine of the Tsushima shrine network - Hiromine Shrine (

広峰 神社 ) in Himeji, Hyōgo Prefecture

Hikawa Shrine network

[edit]The Hikawa Shrine network concentrated in Saitama and Tokyo (historical Musashi Province) also has Susanoo as its focus of worship, often alongside Kushinadahime.

- Hikawa Shrine (

氷川神社 ) in Ōmiya, Saitama, Saitama Prefecture - Hikawa Shrine in Kawagoe, Saitama Prefecture

- Hikawa Shrine in Akasaka, Minato, Tokyo

- Susanoo Shrine in Hamamatsu, Shizuoka Prefecture

In Japanese performing arts

[edit]- The iwami kagura – Orochi

- The jōruri – Nihon Furisode Hajime (

日本 振袖 始 ) by Chikamatsu Monzaemon

Influence outside of Japan

[edit]In the 20th century, Susanoo was depicted as the common ancestor of the modern Koreans while the Japanese were considered to be descendants of Amaterasu during the Japanese occupation of Korea by historians such as Shiratori Kurakichi, founder of the discipline of Oriental History (Tōyōshi

The theory linked the Koreans to Susanoo and in turn the Japanese which ultimately legitimized the colonization of the Korean peninsula by the Japanese.

In popular culture

[edit]Yamata Amasung Keibu Keioiba (English: Yamata-no-Orochi and Keibu Keioiba) is a Meitei language play that interweaves the stories of the two legendary creatures, Yamata-no-Orochi slain by Susanoo of Japanese folklore and Keibu Keioiba of Meitei folklore (Manipuri folklore). In the play, the role of Susanoo was played by Romario Thoudam Paona.[123][124]

Along with Yamato Takeru, he was portrayed by Toshiro Mifune in The Birth of Japan. The film suggests Susanoo's grief over Izanami and resentment towards Izanagi caused his violent rampage.

Family tree

[edit]- Pink is female.

- Blue is male.

- Grey means other or unknown.

- Clans, families, people groups are in green.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Because (A) in the Kojiki, the children borne by Amaterasu but fathered by him were female; or (B) in the Shoki, the children borne by him but mothered by Amaterasu were male.

References

[edit]- ^ Weiss, David (2022). The God Susanoo and Korea in Japan's Cultural Memory: Ancient Myths and Modern Empire. London, United Kingdom. ISBN 978-1-350-27118-0. OCLC 1249629533.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Jump up to: a b Uehara, Toyoaki (1983). "The Shinto Myth – Meaning, Symbolism, and Individuation –". Tenri Journal of Religion (17–18). Tenri University Press: 195.

- ^ Jackson-Laufer, Guida Myrl (1995). Traditional Epics: A Literary Companion. Oxford University Press. p. 556. ISBN 978-0-19-510276-5.

- ^ Matsumoto, Yoshinosuke (1999). The Hotsuma Legends: Paths of the Ancestors. Translated by Driver, Andrew. Japan Translation Centre. p. 92.

- ^ Slawik, Alexander (1984). Nihon Bunka no Kosō (

日本 文化 の古層 ). Mirai-sha. p. 123. - ^ Shintō no Hon: Yaoyorozu no Kamigami ga Tsudou Hikyōteki Saishi no Sekai (

神道 の本 :八百万 の神 々がつどう秘教 的 祭祀 の世界 ). Gakken. 1992. pp. 66–67. ISBN 978-4051060244. - ^ Jump up to: a b Lee, Ki-Moon; Ramsey, S. Robert (2011). A History of the Korean Language. Cambridge University Press. p. 75. ISBN 978-1-139-49448-9.

- ^ Tanigawa, Ken'ichi (1980). Tanigawa Ken'ichi Chosakushū, volume 2 (

谷川 健一 著作 集 第 2巻 ) (in Japanese). Sanʾichi Shobō. p. 161. - ^ Gadeleva, Emilia (2000). "Susanoo: One of the Central Gods in Japanese Mythology". Nichibunken Japan Review: Bulletin of the International Research Center for Japanese Studies. 12. International Research Center for Japanese Studies: 168. doi:10.15055/00000288.

- ^ Ebersole, Gary L., 1950- (1989). Ritual poetry and the politics of death in early Japan. Princeton, N.J. ISBN 0-691-07338-4. OCLC 18560237.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Chamberlain (1882). Section XI.—Investiture of the Three Deities; The Illustrious August Children.

- ^ Chamberlain (1882). Section XII.—The Crying and Weeping of His Impetuous-Male-Augustness.

- ^ Aston, William George (1896). . Nihongi: Chronicles of Japan from the Earliest Times to A.D. 697. Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner & Co. p. – via Wikisource.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Aston, William George (1896). . Nihongi: Chronicles of Japan from the Earliest Times to A.D. 697. Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner & Co. p. – via Wikisource.

- ^ Chamberlain (1882). Section XIII.—The August Oath.

- ^ Aston, William George (1896). . Nihongi: Chronicles of Japan from the Earliest Times to A.D. 697. Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner & Co. p. – via Wikisource.

- ^ Aston, William George (1896). . Nihongi: Chronicles of Japan from the Earliest Times to A.D. 697. Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner & Co. p. – via Wikisource.

- ^ Aston, William George (1896). . Nihongi: Chronicles of Japan from the Earliest Times to A.D. 697. Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner & Co. p. – via Wikisource.

- ^ Aston, William George (1896). . Nihongi: Chronicles of Japan from the Earliest Times to A.D. 697. Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner & Co. p. – via Wikisource.

- ^ Chamberlain (1882). Section XIV.—The August Declaration of the Division of the August Male Children and the August Female Children.

- ^ Chamberlain (1882). Section XV.—The August Ravages of His Impetuous-Male-Augustness.

- ^ Philippi, Donald L. (2015). Kojiki. Princeton University Press. p. 79. ISBN 978-1-4008-7800-0.

- ^ Aston, William George (1896). . Nihongi: Chronicles of Japan from the Earliest Times to A.D. 697. Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner & Co. p. – via Wikisource.

- ^ Chamberlain (1882). Section XVI.—The Door of the Heavenly Rock-Dwelling.

- ^ Aston, William George (1896). . Nihongi: Chronicles of Japan from the Earliest Times to A.D. 697. Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner & Co. p. – via Wikisource.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Chamberlain (1882). Section XVII.—The August Expulsion of His-Impetuous-Male-Augustness.

- ^ Aston, William George (1896). . Nihongi: Chronicles of Japan from the Earliest Times to A.D. 697. Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner & Co. p. – via Wikisource.

- ^ Translation from Philippi, Donald L. (2015). Kojiki. Princeton University Press. pp. 85–86. ISBN 978-1-4008-7800-0. Names (transcribed in Old Japanese in the original) have been changed into their modern equivalents.

- ^ Aston, William George (1896). . Nihongi: Chronicles of Japan from the Earliest Times to A.D. 697. Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner & Co. p. – via Wikisource.

- ^ Aston, William George (1896). . Nihongi: Chronicles of Japan from the Earliest Times to A.D. 697. Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner & Co. p. – via Wikisource.

- ^ Aston, William George (1896). . Nihongi: Chronicles of Japan from the Earliest Times to A.D. 697. Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner & Co. p. – via Wikisource.

- ^ Chamberlain (1882). Section XVIII.—The Eight-Forked Serpent.

- ^ Aston, William George (1896). . Nihongi: Chronicles of Japan from the Earliest Times to A.D. 697. Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner & Co. p. – via Wikisource.

- ^ Translation from Philippi, Donald L. (2015). Kojiki. Princeton University Press. pp. 89–90. ISBN 978-1-4008-7800-0. Names (transcribed in Old Japanese in the original) have been changed into their modern equivalents.

- ^ Aston, William George (1896). . Nihongi: Chronicles of Japan from the Earliest Times to A.D. 697. Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner & Co. p. – via Wikisource.

- ^ Aston, William George (1896). . Nihongi: Chronicles of Japan from the Earliest Times to A.D. 697. Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner & Co. p. – via Wikisource.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Aston, William George (1896). . Nihongi: Chronicles of Japan from the Earliest Times to A.D. 697. Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner & Co. p. – via Wikisource.

- ^ Sesko, Markus (2012). Legends and Stories around the Japanese Sword 2. Lulu.com. p. 23. ISBN 978-1-300-29383-5.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Inbe, Hironari; Katō, Genchi; Hoshino, Hikoshiro (1925). Kogoshui. Gleanings from Ancient Stories. Zaidan-Hojin-Meiji-Seitoku-Kinen-Gakkai (Meiji Japan Society). p. 24.

- ^ Philippi, Donald L. (2015). Kojiki. Princeton University Press. p. 91. ISBN 978-1-4008-7800-0.

- ^ Chamberlain (1882). Section XIX.—The Palace of Suga.

- ^ Chamberlain (1882). Section XX.—The August Ancestors of the Deity-Master-of-the-Great-Land.

- ^ Aston, William George (1896). . Nihongi: Chronicles of Japan from the Earliest Times to A.D. 697. Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner & Co. p. – via Wikisource.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Aston, William George (1896). . Nihongi: Chronicles of Japan from the Earliest Times to A.D. 697. Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner & Co. p. – via Wikisource.

- ^ Chamberlain (1882). SECT. XXIII.—The Nether-Distant-Land.

- ^ Kurita, Hiroshi (1931).

標 註古風土記 出雲 (Hyōchū Kofudoki: Izumo). Ō-Oyakama Shoten. p. 36. - ^ Records of Wind and Earth: A Translation of Fudoki, with Introduction and Commentaries. Translated by Aoki, Michiko Y. Association for Asian Studies, Inc. 1997. p. 83.

- ^ Kurita, Hiroshi (1931).

標 註古風土記 出雲 (Hyōchū Kofudoki: Izumo). Ō-Oyakama Shoten. p. 44. - ^ Records of Wind and Earth: A Translation of Fudoki, with Introduction and Commentaries. Translated by Aoki, Michiko Y. Association for Asian Studies, Inc. 1997. p. 85.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Kurita, Hiroshi (1931).

標 註古風土記 出雲 (Hyōchū Kofudoki: Izumo). Ō-Oyakama Shoten. p. 91. - ^ Records of Wind and Earth: A Translation of Fudoki, with Introduction and Commentaries. Translated by Aoki, Michiko Y. Association for Asian Studies, Inc. 1997. p. 95.

- ^ Records of Wind and Earth: A Translation of Fudoki, with Introduction and Commentaries. Translated by Aoki, Michiko Y. Association for Asian Studies, Inc. 1997. pp. 95–96.

- ^ Kurita, Hiroshi (1931).

標 註古風土記 出雲 (Hyōchū Kofudoki: Izumo). Ō-Oyakama Shoten. pp. 159–160. - ^ Records of Wind and Earth: A Translation of Fudoki, with Introduction and Commentaries. Translated by Aoki, Michiko Y. Association for Asian Studies, Inc. 1997. pp. 109–110.

- ^ Kurita, Hiroshi (1931).

標 註古風土記 出雲 (Hyōchū Kofudoki: Izumo). Ō-Oyakama Shoten. pp. 160–161. - ^ Records of Wind and Earth: A Translation of Fudoki, with Introduction and Commentaries. Translated by Aoki, Michiko Y. Association for Asian Studies, Inc. 1997. p. 110.

- ^ Kurita, Hiroshi (1931).

標 註古風土記 出雲 (Hyōchū Kofudoki: Izumo). Ō-Oyakama Shoten. pp. 266–267. - ^ Records of Wind and Earth: A Translation of Fudoki, with Introduction and Commentaries. Translated by Aoki, Michiko Y. Association for Asian Studies, Inc. 1997. p. 133.

- ^ Kurita, Hiroshi (1931).

標 註古風土記 出雲 (Hyōchū Kofudoki: Izumo). Ō-Oyakama Shoten. p. 270. - ^ Records of Wind and Earth: A Translation of Fudoki, with Introduction and Commentaries. Translated by Aoki, Michiko Y. Association for Asian Studies, Inc. 1997. pp. 133–134.

- ^ Kurita, Hiroshi (1931).

標 註古風土記 出雲 (Hyōchū Kofudoki: Izumo). Ō-Oyakama Shoten. pp. 324–325. - ^ Jump up to: a b Records of Wind and Earth: A Translation of Fudoki, with Introduction and Commentaries. Translated by Aoki, Michiko Y. Association for Asian Studies, Inc. 1997. pp. 140–141.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Kurita, Hiroshi (1931).

標 註古風土記 出雲 (Hyōchū Kofudoki: Izumo). Ō-Oyakama Shoten. pp. 347–348. - ^ Records of Wind and Earth: A Translation of Fudoki, with Introduction and Commentaries. Translated by Aoki, Michiko Y. Association for Asian Studies, Inc. 1997. p. 151.

- ^ Records of Wind and Earth: A Translation of Fudoki, with Introduction and Commentaries. Translated by Aoki, Michiko Y. Association for Asian Studies, Inc. 1997. p. 154.

- ^ Yonei, Teruyoshi. "Gozu Tennō". Encyclopedia of Shinto. Kokugakuin University. Retrieved 31 March 2020.

- ^ Rambelli, Fabio; Teeuwen, Mark, eds. (2003). Buddhas and Kami in Japan: Honji Suijaku as a Combinatory Paradigm. Routledge. pp. 38–39. ISBN 9780203220252.

- ^ "Gozu Tennou

牛頭 天王 ". Japanese Architecture and Art Net Users System (JAANUS). Retrieved 31 March 2020. - ^ "Gozu-Tennō". rodsshinto.com. Retrieved 30 March 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c McMullin, Neil (February 1988). "On Placating the Gods and Pacifying the Populace: The Case of the Gion "Goryō" Cult". History of Religions. 27 (3). The University of Chicago Press: 270–293. doi:10.1086/463123. JSTOR 1062279. S2CID 162357693.

- ^ The Japan Mail. Jappan Mēru Shinbunsha. 11 March 1878. pp. 138–139.

- ^ Hardacre, Helen (2017). Shinto: A History. Oxford University Press. p. 181. ISBN 978-0-19-062171-1.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Akimoto, Kichirō, ed. (1958).

日本 古典 文学 大系 2風土記 (Nihon Koten Bungaku Taikei, 2: Fudoki). Iwanami Shoten. pp. 488–489. - ^ Jump up to: a b Philippi (2015). p. 402.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Gadeleva (2000). pp. 166-167.

- ^ Bonnefoy, Yves, ed. (1993). Asian Mythologies. University of Chicago Press. p. 151. ISBN 978-0-226-06456-7.

- ^ Taniguchi, Masahiro. "Origin of ceremonies of the Imperial court connected with the sun – Deciphering the myths of the Ama no Iwayato". Kokugakuin Media. Retrieved 9 May 2020.

- ^ Gadeleva (2000). p. 167.

- ^ Gadeleva (2000). p. 182.

- ^ Chamberlain (1882). Section XXII.—Mount Tema.

- ^ Gadeleva (2000). pp. 167-168.

- ^ McMullin (1988). pp. 266-267.

- ^ Gadeleva (2000). p. 168.

- ^ Gadeleva (2000). p. 190-194.

- ^ Gadeleva (2000). p. 194-196.

- ^ Philippi (2015). p. 403.

- ^ Philippi (2015). p. 80, footnote 5.

- ^ Gadeleva (2000). p. 173-174.

- ^ Namiki, Kazuko. "Ōharae". Encyclopedia of Shinto. Kokugakuin University. Retrieved 10 May 2020.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Motosawa, Masafumi. "Norito". Encyclopedia of Shinto. Kokugakuin University. Retrieved 10 May 2020.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Philippi (2015). pp. 403-404.

- ^ Aston, William George (1896). . Nihongi: Chronicles of Japan from the Earliest Times to A.D. 697. Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner & Co. p. 40, footnote 185 – via Wikisource.

- ^ Naumann, Nelly (1982). "'Sakahagi': The 'Reverse Flaying' of the Heavenly Piebald Horse". Asian Folklore Studies. 41 (1): 14, 22–25. doi:10.2307/1178306. JSTOR 1178306.

- ^ Gadeleva (2000). p. 190-191.

- ^ Naumann (1982). pp. 29-30.

- ^ Philippi (2015). p. 86, footnote 26-27.

- ^ "Susanoo". Mythopedia.

- ^ "Shinto Portal - IJCC, Kokugakuin University".

- ^ "Shinto Portal - IJCC, Kokugakuin University".

- ^ Nussbaum, Louis-Frédéric (2002). Japan Encyclopedia. Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674017535.

- ^ "Shinto Portal - IJCC, Kokugakuin University".

- ^ "Shinto Portal - IJCC, Kokugakuin University".

- ^ "

御祭 神 ".八坂神社 (Yasaka Shrine Official Website). Retrieved 30 March 2020. - ^ "

厄除 けの神様 ー素 戔嗚尊 (すさのおのみこと)".厄年 ・厄除 け厄払 いドットコム (in Japanese). Retrieved 8 May 2020. - ^ "The Kawagoe Hikawa-jinja shrine of marriage".

川越 水先案内 板 . 17 May 2019. Retrieved 8 May 2020. - ^ "Hikawa Shrine in Kawagoe – 8 Things To Do To Improve Your Luck in Love". Matcha – Japan Travel Web Magazine. Retrieved 8 May 2020.

- ^ "History". Susa Shrine Official Website. Retrieved 30 March 2020.

- ^ "

第 十 八 番 須佐 神社 ".出雲 國神 仏 霊場 を巡 る旅 (Izumo-no-kuni shinbutsu reijo o meguru tabi).社寺 縁座 の会 (Shaji Enza no Kai). Retrieved 30 March 2020. - ^ Jump up to: a b "

須佐 (稲田 )氏 (Susa (Inada)-shi)".家紋 World – World of KAMON. Retrieved 30 March 2020. - ^

飯石 郡 誌 (Iishi-gun shi) (in Japanese).飯石 郡 役所 (Iishi-gun yakusho). 1918. p. 247. - ^ Jump up to: a b

大 日本 神社 志 (Dai-Nippon jinja shi).大 日本 敬神 会 本部 (Dai-Nippon Keishinkai Honbu). 1933. p. 342. - ^ "Dedicated Kami (deities or Japanese gods)". Suga Shrine Official Website. Retrieved 30 March 2020.

- ^ "

第 十 六 番 須我神社 ".出雲 國神 仏 霊場 を巡 る旅 (Izumo-no-kuni shinbutsu reijo o meguru tabi).社寺 縁座 の会 (Shaji Enza no Kai). Retrieved 30 March 2020. - ^ Records of Wind and Earth: A Translation of Fudoki, with Introduction and Commentaries. Translated by Aoki, Michiko Y. Association for Asian Studies, Inc. 1997. p. 153.

- ^ "

八 重 垣 神社 について". 【公式 】八 重 垣 神社 (Yaegaki Shrine Official Website). Retrieved 30 March 2020. - ^ Records of Wind and Earth: A Translation of Fudoki, with Introduction and Commentaries. Translated by Aoki, Michiko Y. Association for Asian Studies, Inc. 1997. p. 90.

- ^ "

八 重 垣 神社 -出雲 国造 家 (Yaegaki Jinja – Izumo-Kokuzō-ke)".家紋 World – World of KAMON. Retrieved 30 March 2020. - ^ "

大神 様 のお話 ".出雲 國 一之宮 熊野 大社 (Kumano Taisha Official Website). Retrieved 30 March 2020. - ^ "Kumano Taisha Shrine".

出雲 國 一之宮 熊野 大社 (Kumano Taisha Official Website). Retrieved 30 March 2020. - ^ "

熊野 大社 (Kumano Taisha)".山陰 観光 【神 々のふるさと山陰 】. Retrieved 30 March 2020. - ^ "

燧 臼 ・燧 杵 ―ひきりうす・ひきりぎね―".出雲 國 一之宮 熊野 大社 (Kumano Taisha Official Website). Retrieved 30 March 2020. - ^ Weiss, David (2022). The God Susanoo and Korea in Japan's Cultural Memory: Ancient Myths and Modern Empire. London, United Kingdom. ISBN 978-1-350-27118-0. OCLC 1249629533.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "YAMATA AMASUNG KEIBU KEIOIBA – 21st Bharat Rang Mahotsav 2020". Archived from the original on 22 April 2021.

- ^ "Heisnam Tomba's Play: Yamata Amasung Keibu Keioiba". StageBuzz. 16 February 2020.

- ^ Kaoru, Nakayama (7 May 2005). "Ōyamatsumi". Encyclopedia of Shinto. Retrieved 29 September 2010.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Chamberlain (1882). Section XIX.—The Palace of Suga.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Chamberlain (1882). Section XX.—The August Ancestors of the Deity-Master-of-the-Great-Land.

- ^ Atsushi, Kadoya (10 May 2005). "Susanoo". Encyclopedia of Shinto. Retrieved 29 September 2010.

- ^ "Susanoo | Description & Mythology". Encyclopedia Britannica.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Herbert, J. (2010). Shinto: At the Fountainhead of Japan. Routledge Library Editions: Japan. Taylor & Francis. p. 402. ISBN 978-1-136-90376-2. Retrieved 21 November 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b

大年 神 [Ōtoshi-no-kami] (in Japanese). Kotobank. Archived from the original on 5 June 2023. Retrieved 5 May 2023. - ^ Jump up to: a b

大年 神 [Ōtoshi-no-kami] (in Japanese). Kokugakuin University. Archived from the original on 5 June 2023. Retrieved 5 May 2023. - ^ Jump up to: a b Mori, Mizue. "Yashimajinumi". Kokugakuin University Encyclopedia of Shinto.

- ^ Frédéric, L.; Louis-Frédéric; Roth, K. (2005). Japan Encyclopedia. Harvard University Press reference library. Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-01753-5. Retrieved 21 November 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "My Shinto: Personal Descriptions of Japanese Religion and Culture". www2.kokugakuin.ac.jp. Retrieved 16 October 2023.

- ^ “‘My Own Inari’: Personalization of the Deity in Inari Worship.” Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 23, no. 1/2 (1996): 87-88

- ^ "Ōtoshi |

國學院大學 デジタルミュージアム". 17 August 2022. Archived from the original on 17 August 2022. Retrieved 14 November 2023. - ^ "Encyclopedia of Shinto - Home : Kami in Classic Texts : Kushinadahime". eos.kokugakuin.ac.jp.

- ^ "Kagutsuchi". World History Encyclopedia.

- ^ Ashkenazi, M. (2003). Handbook of Japanese Mythology. Handbooks of world mythology. ABC-CLIO. p. 213. ISBN 978-1-57607-467-1. Retrieved 21 November 2020.

- ^ Chamberlain, B.H. (2012). Kojiki: Records of Ancient Matters. Tuttle Classics. Tuttle Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4629-0511-9. Retrieved 21 November 2020.

- ^ Philippi, Donald L. (2015). Kojiki. Princeton University Press. p. 92.

- ^ Chamberlain (1882). Section XX.—The August Ancestors of the Deity-Master-Of-The-Great Land.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Ponsonby-Fane, R. A. B. (3 June 2014). Studies In Shinto & Shrines. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-136-89294-3.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Encyclopedia of Shinto - Home : Kami in Classic Texts : Futodama". eos.kokugakuin.ac.jp. Retrieved 13 July 2021.

- ^ Philippi, Donald L. (2015). Kojiki. Princeton University Press. pp. 104–112.

- ^ Atsushi, Kadoya; Tatsuya, Yumiyama (20 October 2005). "Ōkuninushi". Encyclopedia of Shinto. Retrieved 29 September 2010.

- ^ Atsushi, Kadoya (21 April 2005). "Ōnamuchi". Encyclopedia of Shinto. Retrieved 29 September 2010.

- ^ Jump up to: a b The Emperor's Clans: The Way of the Descendants, Aogaki Publishing, 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Varley, H. Paul. (1980). Jinnō Shōtōki: A Chronicle of Gods and Sovereigns. Columbia University Press. p. 89. ISBN 9780231049405.

- ^ Atsushi, Kadoya (28 April 2005). "Kotoshironushi". Encyclopedia of Shinto. Retrieved 29 September 2010.

- ^ Sendai Kuji Hongi, Book 4 (

先代 舊 事 本紀 巻 第 四 ), in Keizai Zasshisha, ed. (1898). Kokushi-taikei, vol. 7 (国史 大系 第 7巻 ). Keizai Zasshisha. pp. 243–244. - ^ Chamberlain (1882). Section XXIV.—The Wooing of the Deity-of-Eight-Thousand-Spears.

- ^ Tanigawa Ken'ichi 『

日本 の神 々神社 と聖地 7山陰 』(新装 復刊 ) 2000年 白水 社 ISBN 978-4-560-02507-9 - ^ Jump up to: a b Kazuhiko, Nishioka (26 April 2005). "Isukeyorihime". Encyclopedia of Shinto. Archived from the original on 21 March 2023. Retrieved 29 September 2010.

- ^ Jump up to: a b 『

神話 の中 のヒメたち もうひとつの古事記 』p94-97「初代 皇后 は「神 の御子 」」 - ^ Jump up to: a b c

日本人 名 大 辞典 +Plus, デジタル版 . "日子 八 井 命 とは". コトバンク (in Japanese). Retrieved 1 June 2022. - ^ Jump up to: a b c ANDASSOVA, Maral (2019). "Emperor Jinmu in the Kojiki". Japan Review (32): 5–16. ISSN 0915-0986. JSTOR 26652947.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Visit Kusakabeyoshimi Shrine on your trip to Takamori-machi or Japan". trips.klarna.com. Retrieved 4 March 2023.

- ^ 『

図説 歴代 天 皇紀 』p42-43「綏靖天皇 」 - ^ Anston, p. 143 (Vol. 1)

- ^ Grapard, Allan G. (28 April 2023). The Protocol of the Gods: A Study of the Kasuga Cult in Japanese History. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-91036-2.

- ^ Tenri Journal of Religion. Tenri University Press. 1968.

- ^ Takano, Tomoaki; Uchimura, Hiroaki (2006). History and Festivals of the Aso Shrine. Aso Shrine, Ichinomiya, Aso City.: Aso Shrine.

Bibliography

[edit]- Aoki, Michiko Y., tr. (1997). Records of Wind and Earth: A Translation of Fudoki, with Introduction and Commentaries. Association for Asian Studies, Inc. ISBN 978-0924304323.

- Aston, William George, tr. (1896). Nihongi: Chronicles of Japan from the Earliest Times to A.D. 697. 2 vols. Kegan Paul. 1972 Tuttle reprint.

- Chamberlain, Basil H., tr. (1919). The Kojiki, Records of Ancient Matters. 1981 Tuttle reprint.

- Gadeleva, Emilia (2000). "Susanoo: One of the Central Gods in Japanese Mythology". Nichibunken Japan Review: Bulletin of the International Research Center for Japanese Studies. 12 (12). International Research Center for Japanese Studies: 168. doi:10.15055/00000288. JSTOR 25791053.

- McMullin, Neil (February 1988). "On Placating the Gods and Pacifying the Populace: The Case of the Gion "Goryō" Cult". History of Religions. 27 (3). The University of Chicago Press: 270–293. doi:10.1086/463123. JSTOR 1062279. S2CID 162357693.

- Philippi, Donald L. (2015). Kojiki. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-1400878000.

External links

[edit]- Susanoo, Encyclopedia of Shinto

- Susano-O no Mikoto, Kimberley Winkelmann, in the Internet Archive as of 5 December 2008

- Shaji Enza no Kai Organization

- Official Website of Susa Shrine (in Japanese)

- Official Website of Yasaka Shrine (in Japanese)

- Official Website of Kumano Taisha (in Japanese)

- Official Website of Hikawa Shrine (Saitama) (in Japanese)

- Official Website of Akasaka Hikawa Shrine (in Japanese)

- Susanoo vs Yamata no Orochi animated depiction