無 政府 狀態

|

权力 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||

|

权力 | |||||

|

|

|||||

| 权力结构 | |||||

|

|

|||||

|

| |||||

词源[编辑]

1902

概 述 [编辑]

人 类学[编辑]

从进

无

国 际关系 [编辑]

政治 哲学 [编辑]

无政府 主 义[编辑]

| 无 |

|---|

|

无

伊 曼努尔·康德 [编辑]

部分 国家 崩 溃后的 无政府 状 态的例 子 [编辑]

英国 内 战(1642年 –1651年 )[编辑]

无

托 马斯·雷 恩 巴 勒:“今 天 我 会 比 之 前 更 开放、更 口 无遮拦地与 你们继续交流 。我 希望 我 们都是 心地 善良 的 人 ,希望 我 们都能 以正直 的 态度对待自己 。如果我 真 的 不信任 你,我 就不会 用 这种断言 。不 过我确实认为我 们现在 讨论的 问题是 一个不信任的问题,因 为人们太容易 把 事情 想 得 太 简单,而有些时候 事情 要 复杂得 多 。就我而言,我 认为你忘记了我 演 讲中的 一 些内容 ,你不仅自己 认为有 些人认为政府 永 远是不正 确的,而且你讨厌所有 相 信 这些的 人 。而且,先生 ,就因为一个人认为人人都应有选举权,你就说这会 毁掉一切财产权——这是在 忽 略 上帝 的 律 法 ,因 为在上帝 的 律 法 中 已 经规定 了 财产权;不 然 上帝 为何说‘汝 不可 行 窃?’难道说,因 为我是 个穷人 ,所以 我 就必须受到压迫,因 为我在 这个王国 中 没 有 财产,我 就必须承受这个王国 的 所有 律 法 ,无论他 们对错吗?或 者 这样说:假 如有一个住在乡镇的,和 他人 一样有三四块庄园领地(天知 道 他 们怎么拿到这些土地 的 )的 乡绅,当 要 选举议会的 时候,他 必然 会 成 为议会 代表 ;这时如果他 看 到 一些在自己门口住的穷人,他 就会去 压榨他 们——我 知道 有 大 批这样的穷人被 轰出门外无家可 归,我 非常 清楚 这些是 那 些富人 做的,以让这些穷人承 受世界 上 最 残酷 的 暴政 。所以 我 认为这个问题已 经得到 了 充分 地 解答 :上帝 把 这件事 与 他 的 这条律 法 规定在 一起 ,即 汝 不可 行 窃。就我而言,我 反 对任何 这种支持 这种有人 没 有 选举权的想 法 ,至 于你们自己 ,我 只 希望 你们不要 让世界 觉得我 们是支持 无政府 状 态的。”奥 利 弗 ·克 伦威尔:“我 只 知道 ,善 于让步 的 人 有 着 大 智慧 。不 过,先生 ,这些条例 并不像 它们看 起 来 那 么好。而且,没 人 说你支持 无政府 状 态,只 是 这些条例 很可能 甚至一定会导致无政府状态。因 为如果 你取消 了 财产限 制 ,那 么就会 导致除 了 呼吸 的 利益 之 外 没 有 任 何 利益 的 人 在 选举中 也有 发言权,那 么哪里 还有什么约束或 限 制 ?不 过,我 还是坚信我 们不必如此针锋相对。”[124]

- 1651

年 ,托 马斯·霍布斯在 《利 维坦》一 书中将 自然 狀態 描述为所有 人 對 所有 人的 戰爭 的 状 态,人 类在这种状 态下过着野蛮 的 生活 :“美 洲 有 许多地方 的 野蛮 民族 除 开小家族 以外 并无其他政府 ,而小家族 的 协调又 完全 取 决于自然 欲望 ,他 们今天 还生活 在 我 在 上面 所 说的那 种野蛮 残忍 的 状 态中”[125][126]。霍布斯在书中进一 步 指出 自然 狀態 中 的 争 斗 主要 是 由 三种原因导致——第 一 是 竞争,第 二 是 猜疑 ,第 三 是 荣誉:“第 一种原因使人为了求利、第 二种原因使人为了求安全、第 三种原因则使人为了求名誉而进行侵犯”[127]。霍布斯在书中进一步总结出了若干条自然 律 ,其中第 一 条 为:“每 一个人只要有获得和平的希望时,就应当 力 求 和平 ;在 不能 得 到 和平 时,他 就可以寻求 并利用 战争的 一切 有利 条件 和 助力 ”。在 自然 状 态中,“每 一个人对每一种事物都具有权利,甚至对彼此 的 身体 也是这样”,因 此,霍布斯的第 二条自然律致力于让人们能够享受和平的好处:“在 别人也愿意 这样做的条件下 ,当 一 个人[……]认为必要 时,会 自 愿 放 弃这种对一切 事物 的 权利;而在对他人 的 自由 权方面 满足于相当 于自己 让他人 对自己 所 具有 的 自由 权利”[128]。这也是 社会 契 约的开始,霍布斯的第 三条自然律即为“所 定信 约必须履行 ”,在 此之上 不履行 社会 契 约就是 不 义的,任 何 不 是 不 义的事物 就是正 义的。 - 1656

年 ,詹姆士 ·哈林顿在 《大洋 国 》一 书中使用 “无政府 状 态”一 词描述 人民 用 武力 将 政府 强 加 在 由 单个人 (君主 專制 )或 由 少数 人 (混合 君主 制 )拥有一切土地所构成的经济基础上的情况。哈灵顿称该词与 共和 国 一词并不相同,后 者 是 指 土地 所有 权和治 理 权都由 广大民 众共享 的 状 态,哈林顿认为无政府 状 态是一种暂时的状态,是 由 政府 形式 和 财产关系形式 之 间的均 势被破 坏引起 的 [129]。

阿 尔巴尼 亚(1997年 )[编辑]

1997

索 马里(1991年 –2006年 )[编辑]

1991

虽然

经济

无政府 主 义运动[编辑]

俄 国内 战(1917年 –1922年 )[编辑]

1917

1918

马赫诺视

西 班 牙 (1936年 )[编辑]

秉持

无治社 区 列 表 [编辑]

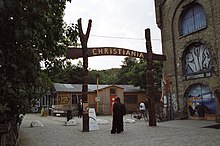

无治社 区 [编辑]

佐 米 亚,缺 少 政府 管理 的 东南亚高地 科 斯帕亚共和国 [145](1440年 –1826年 )- 挖掘

派 (位 于英格 兰,1649年 –1651年 ) 利 贝塔蒂亚(海 盗 政 权,成立 于17世 纪晚期 )- 莫雷斯内

特 [146](1816年 6月 26日 –1919年 6月 28日 ) 九 龍 寨城,曾位于香港 的 长期基本 不 存在 政府 管理 的 区域 落城 ,第 一座 嬉 皮 士 城市 公社 (位 于科罗拉多 ,1965年 –1977年 )反抗 群 体 ,美 洲 原住民 运动(位 于危地 马拉,1988年 –)[147]- 斯拉

布 城 ,由 居住 在 露 营车上 的 人 组成的 沙漠 社 区 (位 于加利 福 尼 亚,1965年 –) 棚 户区居 民 运动,南 非 社会 运动(2005年 –)[148]- Ras Khamis

国会 山 自治 区 (位 于西雅 图,2020年 )[149]

无政府 主 义社区 [编辑]

无

意 识社区

群 众社会

- 马赫诺运动(

位 于乌克 兰,1918年 11月–1921年 ) 革命 加 泰 罗尼亚(1936年 7月 21日 –1939年 5月 )在 满韩族 总联合 会 (1929年 –1931年 )埃 尔阿尔托社 区 委 员会联合会 (1979年 –)反 叛萨帕塔自治 市 镇(1994年 –)羅 賈瓦(2012年 –)

參 見 [编辑]

参考 文献 [编辑]

- ^

安 那 其主义思想 .中 文 马克思 主 义文库. [2021-09-30]. (原始 内容 存 档于2021-08-18). - ^ Ning, Ou; Bing, Li; Sipei, Lu. Bishan project: Efforts to build a utopian community under authoritarian rule. Curating Under Pressure (Routledge). 2020 [2021-09-30]. doi:10.4324/9780815396215-7/bishan-project-ou-ning-li-bing-lu-sipei. (

原始 内容 存 档于2021-09-30).In the Chinese context, I prefer to transliterate anarchy as An Na Qi (Chinese:

安 那 其). - ^ 3.0 3.1 Benjamin Franks; Nathan Jun; Leonard Williams. Anarchism: A Conceptual Approach. Taylor & Francis. 2018: 104–. ISBN 978-1-317-40681-5.

Anarchism can be defined in terms of a rejection of hierarchies, such as capitalism, racism or sexism, a social view of freedom in which access to material resources and liberty of others as prerequisites to personal freedom [...].

- ^ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Anarchy. Merriam-webster.com. [2020-01-22]. (

原始 内容 存 档于2017-12-25). - ^ 5.0 5.1 Proudhon, Pierre-Joseph. Qu'est-ce que la propriété ? ou Recherche sur le principe du Droit et du Gouvernement 1st. Paris: Brocard. 1840: 235 [2021-08-04]. (

原始 内容 存 档于2021-05-12) (法 语). - ^ 6.0 6.1 Proudhon, Piere-Joseph. Kelley, Donald R.; Smith, Bonnie G. , 编. Proudhon: What is Property?. Cambridge University Press. 1994: 209 [2021-08-04]. ISBN 978-0-521-40556-0. (

原始 内容 存 档于2021-12-01).[S]ociety seeks order in anarchy.

- ^ 7.0 7.1

普 魯東,皮 埃 爾 -約 瑟夫. 什么是 所有 权.由 孙,署 冰翻译 1.北京 :商 务印书馆. 1963-02: 288. ISBN 9787100011754.社会 则在无政府 状 态中寻求秩序 。 - ^ Tamblyn, Nathan (2019-04-30). "The Common Ground of Law and Anarchism". Liverpool Law Review. 40 (1): 65–78. doi:10.1007/s10991-019-09223-1.

- ^ Kinna, Ruth (2019-04-24). "Anarchism". Oxford Bibliographies. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/OBO/9780199756384-0059.

- ^ McElroy, Wendy. Benjamin Tucker, Liberty, and Individualist Anarchism (PDF). The Independent Review. Winter 1998, II (3): 425 [2021-08-06]. (

原始 内容 存 档 (PDF)于2019-01-23). - ^

蒲 鲁东学 说(麦 利 荪,1941年 11月).中 文 马克思 主 义文库. [2021-08-06]. (原始 内容 存 档于2021-08-17). - ^ Kirkup, Thomas.

俄 羅 斯大風潮 .由 马君武 翻 译.少年 中國 學會 . 1902 [2021-08-10]. (原始 内容 存 档于2021-09-06). - ^

胡 , 庆云.中国 无政府 主 义思想 史 1.北京 :国防 大学 出版 社 . 1994-02: 41–42 [2021-08-04]. ISBN 7-5626-0498-3. (原始 内容 存 档于2021-10-21). - ^

徐 ,善 广;柳 , 剑平.中国 无政府 主 义史 1.武 汉:湖北 人民 出版 社 . 1989: 23–28 [2021-08-10]. ISBN 7-216-00337-3. (原始 内容 存 档于2021-10-21). - ^ Gowdy, John M. Limited Wants, Unlimited Means: A Reader on Hunter-Gatherer Economics and the Environment. St Louis: Island Press. 1998: 342. ISBN 1-55963-555-X.

- ^ Dahlberg, Frances. Woman the Gatherer. London: Yale University Press. 1975 [2021-08-06]. ISBN 0-300-02989-6. (

原始 内容 存 档于2021-04-16). - ^

格 雷 伯 ,大 卫. 无政府 主 义人类学碎片 .由 许, 煜翻译 1.桂 林 : 广西人民 出版 社 . 2014: 27 [2021-08-06]. ISBN 9787549555277. (原始 内容 存 档于2021-08-06).这样说他们都

真 的 是 无政府 社会 ,建立 在 明 确排除 国家 和市 场的逻辑的 基 础上。 - ^ Graeber, David. Fragments of an Anarchist Anthropology [无

政府 主 义人类学碎片 ] (PDF). Chicago: Prickly Paradigm Press. 2004. ISBN 0-9728196-4-9. (原始 内容 (PDF)存 档于2008-11-18). - ^ Erdal, D.; Whiten, A. On human egalitarianism: an evolutionary product of Machiavellian status escalation?. Current Anthropology. 1994, 35 (2): 175–183. S2CID 53652577. doi:10.1086/204255.

- ^ Erdal, D. and A. Whiten 1996. Egalitarianism and Machiavellian intelligence in human evolution. In P. Mellars and K. Gibson (eds), Modelling the early human mind. Cambridge: McDonald Institute Monographs.

- ^ Christopher Boehm (2001), Hierarchy in the Forest: The Evolution of Egalitarian Behavior, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- ^

格 雷 伯 ,大 卫. 无政府 主 义人类学碎片 .由 许, 煜翻译 1.桂 林 : 广西人民 出版 社 . 2014: 13 [2021-08-06]. ISBN 9787549555277. (原始 内容 存 档于2021-08-06).因 为我认为这正是 人 类学特 别能帮上忙 的 地方 。 - ^ Graeber, David. Fragments of an anarchist anthropology 2nd pr. Chicago: Prickly Paradigm Press. 2004. ISBN 978-0972819640.

- ^

魏 明德 .高 歇的「宗教 退出 」說 與 中國 宗教 格 局 重 構的哲學 思考 .哲學 與 文化 . 2011-10-01, 38 (10) [2021-08-07]. ISSN 1015-8383. doi:10.7065/MRPC.201110.0165. (原始 内容 存 档于2021-08-07). - ^ Clastres, Pierre. Society Against the State: Essays in Political Anthropology. Robert Hurley; Abe Stein (translators). New York: Zone Books. 1989. ISBN 0-942299-01-9.

- ^ Scott, James. The Art of Not Being Governed. Yale University Press. 2010. ISBN 978-0300169171.

- ^ Scott, James C.

逃避 统治的 艺术: 东南亚高地 的 无政府 主 义历史 .由 王 晓毅翻 译.北京 :生活 ·读书·新知 三 联书店 . 2016-01 [2021-08-10]. ISBN 978-7-108-05642-9. (原始 内容 存 档于2021-08-10). - ^ Leeson, Peter. Pirates, Prisoners, and Preliterates: Anarchic Context and the Private Enforcement of Law (PDF). European Journal of Law and Economics. 2014, 37 (3): 365–379 [2021-08-06]. S2CID 41552010. doi:10.1007/s10657-013-9424-x. (

原始 内容 存 档 (PDF)于2021-09-26). - ^

人 类如何 驯化自己 ?. cnBeta.新 浪 科技 . [2021-08-06]. (原始 内容 存 档于2021-08-06) (中 文 (中国 大 陆)). - ^ Zerzan, John. Running on Emptiness: The Pathology of Civilization. Feral House. 2002. ISBN 0-922915-75-X.

- ^ Shepard, Paul. Traces of an Omnivore. Island Press. 1996. ISBN 1-55963-431-6.

- ^ The Consequences of Domestication and Sedentism by Emily Schultz, et al. Primitivism.com. [2012-01-30]. (

原始 内容 存 档于2009-07-15). - ^ Seven Lies About Civilization, Ran Prieur. Greenanarchy.org. [2012-01-30]. (

原始 内容 存 档于2009-10-02). - ^ Kaczynski, Ted. The Unabomber Trial: The Manifesto [论工业社

会 及其未来 ]. The Washington Post. 1995-09-22 [2021-08-06]. (原始 内容 存 档于2016-03-04). - ^

潘 , 亚玲; 时,殷 弘 . 论霍布 斯的国 际关系 哲学 .欧 洲 . 1999, (06): 17 [2021-08-06]. ISSN 1000-3576. (原始 内容 存 档于2021-08-06).尽 管 国家 间可以为某 些目的 达成有限 契 约,但 这完全 不等 于可对它们实施 强制 的 国 际公共 权威,也没有 改 变国际政治 中 的 普遍 冲突状 态。 - ^ Lechner, Silviya (2017-11). "Anarchy in International Relations". International Studies Association. Oxford University Press. pp. 1–26. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780190846626.013.79

- ^ Eckstein, Arthur M.; et al. (2020-09-08). "Anarchy" (页面

存 档备份,存 于互联网档案 馆). Encyclopedia Britannica Online. Retrieved 2020-09-16. - ^ "as many anarchists have stressed, it is not government as such that they find objectionable, but the hierarchical forms of government associated with the nation state". Judith Suissa. Anarchism and Education: a Philosophical Perspective. Routledge. New York. 2006. p. 7

- ^ 39.0 39.1 IAF principles. International of Anarchist Federations. (

原始 内容 存 档于2012-01-05).The IAF–IFA fights for : the abolition of all forms of authority whether economical, political, social, religious, cultural or sexual.

- ^ "That is why Anarchy, when it works to destroy authority in all its aspects, when it demands the abrogation of laws and the abolition of the mechanism that serves to impose them, when it refuses all hierarchical organisation and preaches free agreement – at the same time strives to maintain and enlarge the precious kernel of social customs without which no human or animal society can exist." Peter Kropotkin. Anarchism: its philosophy and ideal 互联网档

案 馆的 存 檔,存 档日期 2012-03-18. - ^ "anarchists are opposed to irrational (e.g., illegitimate) authority, in other words, hierarchy – hierarchy being the institutionalisation of authority within a society." "B.1 Why are anarchists against authority and hierarchy?" 互联网档

案 馆的 存 檔,存 档日期 2012-06-15. in An Anarchist FAQ - ^ "[Anarchism], a social philosophy that rejects authoritarian government and maintains that voluntary institutions are best suited to express man's natural social tendencies." George Woodcock. "Anarchism" in The Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- ^ "In a society developed on these lines, the voluntary associations which already now begin to cover all the fields of human activity would take a still greater extension so as to substitute themselves for the state in all its functions." Peter Kropotkin. "Anarchism" from the Encyclopædia Britannica 互联网档

案 馆的 存 檔,存 档日期 2012-01-06. - ^ Craig, Edward. Anarchism. The Shorter Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Routledge. : 14 [2021-08-07]. ISBN 978-1-134-34408-6. (

原始 内容 存 档于2021-08-07).Anarchism is the view that a society without the state, or government, is both possible and desirable.

- ^ Sheehan, Sean. Anarchism, London: Reaktion Books Ltd., 2004. p. 85

- ^ Malatesta, Errico. Towards Anarchism. MAN! (Los Angeles: International Group of San Francisco). OCLC 3930443. (

原始 内容 存 档于2012-11-07). Agrell, Siri. Working for The Man. The Globe and Mail. 2007-05-14 [2008-04-14]. (原始 内容 存 档于2007-05-16). Anarchism. Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica Premium Service. 2006 [2006-08-29]. (原始 内容 存 档于2006-12-14). Anarchism. The Shorter Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy. 2005: 14.Anarchism is the view that a society without the state, or government, is both possible and desirable.

下 列 来 源 认为无政府 主 义是一 种政治 哲学 :Mclaughlin, Paul. Anarchism and Authority. Aldershot: Ashgate. 2007: 59. ISBN 978-0754661962. Johnston, R. The Dictionary of Human Geography. Cambridge: Blackwell Publishers. 2000: 24. ISBN 0-631-20561-6. - ^ 47.0 47.1 Slevin, Carl. "Anarchism." The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Politics. Ed. Iain McLean and Alistair McMillan. Oxford University Press, 2003.

- ^ McLaughlin, Paul (2007). Anarchism and Authority: A Philosophical Introduction to Classical Anarchism. Ashgate. pp. 28 (页面

存 档备份,存 于互联网档案 馆)–166. ISBN 9780754661962. "Anarchists do reject the state, as we will see. But to claim that this central aspect of anarchism is definitive is to sell anarchism short. [...] [Opposition to the state] is (contrary to what many scholars believe) not definitive of anarchism." - ^ Jun, Nathan (September 2009). "Anarchist Philosophy and Working Class Struggle: A Brief History and Commentary". WorkingUSA. 12 (3): 505–519. doi:10.1111/j.1743-4580.2009.00251.x. ISSN 1089-7011. "One common misconception, which has been rehearsed repeatedly by the few Anglo-American philosophers who have bothered to broach the topic [...] is that anarchism can be defined solely in terms of opposition to states and governments" (p. 507).

- ^ Franks, Benjamin (August 2013). Freeden, Michael; Stears, Marc (eds.). "Anarchism". The Oxford Handbook of Political Ideologies. Oxford University Press: 385–404. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199585977.013.0001. "[M]any, questionably, regard anti-statism as the irremovable, universal principle at the core of anarchism. [...] The fact that [anarchists and anarcho-capitalists] share a core concept of 'anti-statism', which is often advanced as [...] a commonality between them [...], is insufficient to produce a shared identity [...] because [they interpret] the concept of state-rejection [...] differently despite the initial similarity in nomenclature" (pp. 386–388).

- ^ 51.0 51.1 Jennings, Jeremy (1993). "Anarchism". In Eatwell, Roger; Wright, Anthony (eds.). Contemporary Political Ideologies. London: Pinter. pp. 127–146. ISBN 978-0-86187-096-7. "[...] anarchism does not stand for the untrammelled freedom of the individual (as the 'anarcho-capitalists' appear to believe) but, as we have already seen, for the extension of individuality and community" (p. 143).

- ^ 52.0 52.1 Gay, Kathlyn; Gay, Martin (1999). Encyclopedia of Political Anarchy. ABC-CLIO. p. 15. ISBN 978-0-87436-982-3. "For many anarchists (of whatever persuasion), anarcho-capitalism is a contradictory term, since 'traditional' anarchists oppose capitalism".

- ^ 53.0 53.1 Morriss, Andrew (2008). "Anarcho-capitalism". In Hamowy, Ronald (ed.). The Encyclopedia of Libertarianism. SAGE; Cato Institute. pp. 13–14. doi:10.4135/9781412965811.n8. ISBN 978-1-4129-6580-4. OCLC 191924853. "Social anarchists, those anarchists with communitarian leanings, are critical of anarcho-capitalism because it permits individuals to accumulate substantial power through markets and private property."

- ^ 54.0 54.1 Franks, Benjamin (August 2013). Freeden, Michael; Stears, Marc (eds.). "Anarchism". The Oxford Handbook of Political Ideologies. Oxford University Press: 385–404. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199585977.013.0001. "Individualisms that defend or reinforce hierarchical forms such as the economic-power relations of anarcho-capitalism [...] are incompatible with practices of social anarchism. [...] Increasingly, academic analysis has followed activist currents in rejecting the view that anarcho-capitalism has anything to do with social anarchism" (pp. 393–394).

- ^ Goodrick-Clarke, Nicholas. Black Sun: Aryan Cults, Esoteric Nazism and the Politics of Identity. New York: New York University Press. 2003. ISBN 978-0-8147-3155-0.

- ^ Griffin, Roger. From slime mould to rhizome: an introduction to the groupuscular right. Patterns of Prejudice. March 2003, 37 (1): 27–63. S2CID 143709925. doi:10.1080/0031322022000054321.

- ^ Macklin, Graham D. Co-opting the Counter Culture: Troy Southgate and the National Revolutionary Faction. Patterns of Prejudice. September 2005, 39 (3): 301–326 [2021-08-07]. S2CID 144248307. doi:10.1080/00313220500198292. (

原始 内容 存 档于2021-02-05). - ^ Sykes, Alan. The Radical Right in Britain: Social Imperialism to the BNP (British History in Perspective). New York: Palgrave Macmillan. 2005. ISBN 978-0-333-59923-5.

- ^ Sunshine, Spencer. Rebranding Fascism: National-Anarchists. The Public Eye. Winter 2008, 23 (4): 1, 12 [2009-11-12]. (

原始 内容 存 档于2009-07-26). - ^ Sanchez, Casey. 'National Anarchism': California racists claim they're Anarchists. Intelligence Report. Summer 2009 [2009-12-02]. (

原始 内容 存 档于2016-02-24). - ^ Lyons, Matthew N. Rising Above the Herd: Keith Preston's Authoritarian Anti-Statism. New Politics. Summer 2011, 7 (3) [2019-07-27]. (

原始 内容 存 档于2019-07-27). - ^ Funnell, Warwick (2007). "Accounting and the Virtues of Anarchy" (页面

存 档备份,存 于互联网档案 馆). Australasian Accounting, Business and Finance Journal. 1 (1) 18–27. doi:10.14453/aabfj.v1i1.2. - ^ Robinson, Christine M. (2009). "The Continuing Significance of Class: Confronting Capitalism in an Anarchist Community". Working USA. 12 (3): 355–370. doi:10.1111/j.1743-4580.2009.00243.x.

- ^ El-Ojeili, Chamsy (2012). "Anarchism as the Contemporary Spirit of Anti-Capitalism? A Critical Survey of Recent Debates". Critical Sociology. 40 (3): 451–468. doi:10.1177/0896920512452023.

- ^ Williams, Dana (2012). "From Top to Bottom, a Thoroughly Stratified World: An Anarchist View of Inequality and Domination". Race, Gender & Class. 19 (3/4): 9–34. .

- ^ White, Richard; Williams, Colin (2014). "Anarchist Economic Practices in a 'Capitalist' Society: Some Implications for Organisation and the Future of Work" (页面

存 档备份,存 于互联网档案 馆). Ephermera: Theory and Politics in Organization. 14 (4): 947–971. SSRN 2707308. - ^ Casey, Gerard. Freedom's Progress?. Andrews UK Limited. 2018: 670. ISBN 978-1845409425.

- ^ Murray Bookchin (1982). The Ecology of Freedom: The Emergence and Dissolution of Hierarchy. Palo Alto, California: Cheshire Books. p. 3. "My use of the word hierarchy in the subtitle of this work is meant to be provocative. There is a strong theoretical need to contrast hierarchy with the more widespread use of the words class and State; careless use of these terms can produce a dangerous simplification of social reality. To use the words hierarchy, class, and State interchangeably, as many social theorists do, is insidious and obscurantist. This practice, in the name of a "classless" or "libertarian" society, could easily conceal the existence of hierarchical relationships and a hierarchical sensibility, both of which-even in the absence of economic exploitation or political coercion-would serve to perpetuate unfreedom."

- ^ Paul McLaughlin (2007). Anarchism and Authority: A Philosophical Introduction to Classical Anarchism (页面

存 档备份,存 于互联网档案 馆). AshGate. p. 1. "Authority is defined in terms of the right to exercise social control (as explored in the "sociology of power") and the correlative duty to obey (as explored in the "philosophy of practical reason"). Anarchism is distinguished, philosophically, by its scepticism towards such moral relations – by its questioning of the claims made for such normative power – and, practically, by its challenge to those "authoritative" powers which cannot justify their claims and which are therefore deemed illegitimate or without moral foundation." - ^ Emma Goldman. "What it Really Stands for Anarchy" in Anarchism and Other Essays. "Anarchism, then, really stands for the liberation of the human mind from the dominion of religion; the liberation of the human body from the dominion of property; liberation from the shackles and restraint of government. Anarchism stands for a social order based on the free grouping of individuals for the purpose of producing real social wealth; an order that will guarantee to every human being free access to the earth and full enjoyment of the necessities of life, according to individual desires, tastes, and inclinations."

- ^ Benjamin Tucker. Individual Liberty (页面

存 档备份,存 于互联网档案 馆). Individualist anarchist Benjamin Tucker defined anarchism as opposition to authority, as follows: "They found that they must turn either to the right or to the left, – follow either the path of Authority or the path of Liberty. Marx went one way; Warren and Proudhon the other. Thus were born State Socialism and Anarchism ... Authority, takes many shapes, but, broadly speaking, her enemies divide themselves into three classes: first, those who abhor her both as a means and as an end of progress, opposing her openly, avowedly, sincerely, consistently, universally; second, those who profess to believe in her as a means of progress, but who accept her only so far as they think she will subserve their own selfish interests, denying her and her blessings to the rest of the world; third, those who distrust her as a means of progress, believing in her only as an end to be obtained by first trampling upon, violating, and outraging her. These three phases of opposition to Liberty are met in almost every sphere of thought and human activity. representatives of the first are seen in the Catholic Church and the Russian autocracy; of the second, in the Protestant Church and the Manchester school of politics and political economy; of the third, in the atheism of Gambetta and the socialism of Karl Marx." - ^ Ward, Colin. Anarchism as a Theory of Organization. 1966 [2010-03-01]. (

原始 内容 存 档于25 March 2010). - ^ Anarchist historian George Woodcock report of Mikhail Bakunin's anti-authoritarianism and shows opposition to both state and non-state forms of authority as follows: "All anarchists deny authority; many of them fight against it." (p. 9) ... Bakunin did not convert the League's central committee to his full program, but he did persuade them to accept a remarkably radical recommendation to the Berne Congress of September 1868, demanding economic equality and implicitly attacking authority in both Church and State."

- ^ Brown, L. Susan. Anarchism as a Political Philosophy of Existential Individualism: Implications for Feminism. The Politics of Individualism: Liberalism, Liberal Feminism and Anarchism. Black Rose Books Ltd. Publishing. 2002: 106.

- ^ Sylvan, Richard. Anarchism. Goodwin, Robert E.; Pettit, Philip (编). A Companion to Contemporary Political Philosophy. Blackwell Publishing. 1995: 231.

- ^ Ostergaard, Geoffrey. "Anarchism". The Blackwell Dictionary of Modern Social Thought. Blackwell Publishing. p. 14.

- ^ Kropotkin, Peter. Anarchism: A Collection of Revolutionary Writings. Courier Dover Publications. 2002: 5. ISBN 0-486-41955-X.

- ^ R.B. Fowler. The Anarchist Tradition of Political Thought. Western Political Quarterly (University of Utah). 1972, 25 (4): 738–52. JSTOR 446800. doi:10.2307/446800.

- ^ Brooks, Frank H. The Individualist Anarchists: An Anthology of Liberty (1881–1908). Transaction Publishers. 1994: xi. ISBN 1-56000-132-1.

- ^ Joseph Kahn. Anarchism, the Creed That Won't Stay Dead; The Spread of World Capitalism Resurrects a Long-Dormant Movement. The New York Times. 2000, (5 August).

- ^ Colin Moynihan. Book Fair Unites Anarchists. In Spirit, Anyway. New York Times. 2007, (16 April).

- ^ Osgood, Herbert L. (March 1889). "Scientific Anarchism". Political Science Quarterly. The Academy of Political Science. 4 (1): 1–36. doi:10.2307/2139424. JSTOR 2139424. "In anarchism we have the extreme antithesis of [state] socialism and [authoritarian] communism" (p. 1).

- ^ Guérin, Daniel (1970). Anarchism: From Theory to Practice. Monthly Review Press. p. 12. ISBN 9780853451280. "[A]narchism is really a synonym for socialism. The anarchist is primarily a socialist whose aim is to abolish the exploitation of man by man. Anarchism is only one of the streams of socialist thought, that stream whose main components are concern for liberty and haste to abolish the State."55-6. "In general anarchism is closer to socialism than liberalism. [...] Anarchism finds itself largely in the socialist camp, but it also has outriders in liberalism. It cannot be reduced to socialism, and is best seen as a separate and distinctive doctrine."

- ^ Jennings, Jeremy (1999). "Anarchism". In Eatwell, Roger; Wright, Anthony (eds.). Contemporary Political Ideologies (reprinted, 2nd ed.). London: A & C Black. ISBN 9780826451736. p. 147.

- ^ Walter, Nicholas (2002). About Anarchism. London: Freedom Press. p. 44. ISBN 9780900384905. "[A]narchism does derive from liberalism and socialism both historically and ideologically. [...] In a sense, anarchists always remain liberals and socialists, and whenever they reject what is good in either they betray anarchism itself. [...] We are liberals but more so, and socialists but more so."

- ^ Newman, Michael (2005). Socialism: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 15. ISBN 9780192804310.

- ^ Morriss, Brian (2015). Anthropology, Ecology, and Anarchism: A Brian Morris Reader. Marshall, Peter (illustrated ed.). Oakland: PM Press. p. 64. ISBN 9781604860931. "The tendency of writers like David Pepper (1996) to create a dichotomy between socialism and anarchism is both conceptually and historically misleading."

- ^ Guérin, Daniel (1970). Anarchism: From Theory to Practice. Monthly Review Press. p. 70. ISBN 9780853451280. "The anarchists were unanimous in subjecting authoritarian socialism to a barrage of severe criticism. At the time when they made violent and satirical attacks there were not entirely well founded, for those to whom they were addressed were either primitive or 'vulgar' communists, whose thought had not yet been fertilized by Marxist humanism, or else, in the case of Marx and Engels themselves, were not as set on authority and state control as the anarchists made out."

- ^ Post-left anarcho-communist Bob Black after analysing insurrectionary anarcho-communist Luigi Galleani's view on anarcho-communism went as far as saying that "communism is the final fulfillment of individualism.... The apparent contradiction between individualism and communism rests on a misunderstanding of both.... Subjectivity is also objective: the individual really is subjective. It is nonsense to speak of 'emphatically prioritizing the social over the individual'.... You may as well speak of prioritizing the chicken over the egg. Anarchy is a 'method of individualization'. It aims to combine the greatest individual development with the greatest communal unity."Bob Black. Nightmares of Reason. (页面

存 档备份,存 于互联网档案 馆) - ^ Max Baginski. "Stirner: The Ego and His Own" (页面

存 档备份,存 于互联网档案 馆). Mother Earth. Vol. 2. No. 3 May 1907. "Modern Communists are more individualistic than Stirner. To them, not merely religion, morality, family and State are spooks, but property also is no more than a spook, in whose name the individual is enslaved – and how enslaved!...Communism thus creates a basis for the liberty and Eigenheit of the individual. I am a Communist because I am an Individualist. Fully as heartily the Communists concur with Stirner when he puts the word take in place of demand – that leads to the dissolution of property, to expropriation. Individualism and Communism go hand in hand." - ^ "This stance puts him squarely in the libertarian socialist tradition and, unsurprisingly, (Benjamin) Tucker referred to himself many times as a socialist and considered his philosophy to be "Anarchistic socialism." "An Anarchist FAQby Various Authors

- ^ "Because revolution is the fire of our will and a need of our solitary minds; it is an obligation of the libertarian aristocracy. To create new ethical values. To create new aesthetic values. To communalize material wealth. To individualize spiritual wealth." [1] (页面

存 档备份,存 于互联网档案 馆)Renzo Novatore. Toward the Creative Nothing - ^ Suissa, Judith (2001). "Anarchism, Utopias and Philosophy of Education". Journal of Philosophy of Education. 35 (4): 627–646. doi:10.1111/1467-9752.00249

- ^ Skirda, Alexandre. Facing the Enemy: A History of Anarchist Organization from Proudhon to May 1968. AK Press, 2002, p. 191.

- ^ McKay, Iain (编). An Anarchist FAQ I/II. Stirling: AK Press. 2012. ISBN 9781849351225.

No, far from it. Most anarchists in the late nineteenth century recognised communist-anarchism as a genuine form of anarchism and it quickly replaced collectivist anarchism as the dominant tendency. So few anarchists found the individualist solution to the social question or the attempts of some of them to excommunicate social anarchism from the movement convincing.

- ^ Catalan historian Xavier Diez reports that the Spanish individualist anarchist press was widely read by members of anarcho-communist groups and by members of the anarcho-syndicalist trade union CNT. There were also the cases of prominent individualist anarchists such as Federico Urales and Miguel Giménez Igualada who were members of the CNT and J. Elizalde who was a founding member and first secretary of the Iberian Anarchist Federation. Xavier Diez. El anarquismo individualista en España: 1923–1938. ISBN 978-84-96044-87-6

- ^ Within the synthesist anarchist organization, the Fédération Anarchiste, there existed an individualist anarchist tendency alongside anarcho-communist and anarchosyndicalist currents. Individualist anarchists participating inside the Fédération Anarchiste included Charles-Auguste Bontemps, Georges Vincey and André Arru. "Pensée et action des anarchistes en France : 1950–1970" by Cédric GUÉRIN

- ^ In Italy in 1945, during the Founding Congress of the Italian Anarchist Federation, there was a group of individualist anarchists led by Cesare Zaccaria who was an important anarchist of the time.Cesare Zaccaria (19 August 1897 – October 1961) by Pier Carlo Masini and Paul Sharkey (页面

存 档备份,存 于互联网档案 馆) - ^ "Resiting the Nation State, the pacifist and anarchist tradition" by Geoffrey Ostergaard. Ppu.org.uk. 1945-08-06 [2010-09-20]. (

原始 内容 存 档于2011-05-14). - ^ George Woodcock. Anarchism: A History of Libertarian Ideas and Movements (1962)

- ^ Fowler, R.B. "The Anarchist Tradition of Political Thought." The Western Political Quarterly, Vol. 25, No. 4. (1972-12), pp. 743–44.

- ^ Nettlau, Max. A Short History of Anarchism. Freedom Press. 1996: 162. ISBN 0-900384-89-1.

- ^ Daniel Guérin. Anarchism: From Theory to Practice (页面

存 档备份,存 于互联网档案 馆). "At the end of the century in France, Sebastien Faure took up a word originated in 1858 by one Joseph Déjacque to make it the title of a journal, Le Libertaire. Today the terms 'anarchist' and 'libertarian' have become interchangeable." - ^ 104.0 104.1 Marshall, Peter (1992). Demanding the Impossible: A History of Anarchism. London: HarperCollins. pp. 564–565. ISBN 978-0-00-217855-6. "Anarcho-capitalists are against the State simply because they are capitalists first and foremost. [...] They are not concerned with the social consequences of capitalism for the weak, powerless and ignorant. [...] As such, anarcho-capitalism overlooks the egalitarian implications of traditional individualist anarchists like Spooner and Tucker. In fact, few anarchists would accept the 'anarcho-capitalists' into the anarchist camp since they do not share a concern for economic equality and social justice. Their self-interested, calculating market men would be incapable of practising voluntary co-operation and mutual aid. Anarcho-capitalists, even if they do reject the state, might therefore best be called right-wing libertarians rather than anarchists."

- ^ 105.0 105.1 Goodway, David (2006). Anarchist Seeds Beneath the Snow: Left-Libertarian Thought and British Writers from William Morris to Colin Ward. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press. p. 4. "'Libertarian' and 'libertarianism' are frequently employed by anarchists as synonyms for 'anarchist' and 'anarchism', largely as an attempt to distance themselves from the negative connotations of 'anarchy' and its derivatives. The situation has been vastly complicated in recent decades with the rise of anarcho-capitalism, 'minimal statism' and an extreme right-wing laissez-faire philosophy advocated by such theorists as Rothbard and Nozick and their adoption of the words 'libertarian' and 'libertarianism'. It has therefore now become necessary to distinguish between their right libertarianism and the left libertarianism of the anarchist tradition."

- ^ Newman, Saul (2010). The Politics of Postanarchism. Edinburgh University Press. p. 43. "It is important to distinguish between anarchism and certain strands of right-wing libertarianism which at times go by the same name (for example, Rothbard's anarcho-capitalism)." ISBN 0748634959.

- ^ 107.0 107.1 107.2 Carlson, Jennifer D. (2012). "Libertarianism". In Miller, Wilburn R., ed. The Social History of Crime and Punishment in America. London: SAGE Publications. p. 1006 (页面

存 档备份,存 于互联网档案 馆). ISBN 1412988764. - ^ Perlin, Terry M. Contemporary Anarchism. Transaction Publishers. 1979: 40. ISBN 0-87855-097-6.

- ^ Noam Chomsky; Carlos Peregrín Otero. Language and Politics. AK Press. 2004: 739. ISBN 9781902593821.

- ^ Marshall, Peter (1992). Demanding the Impossible: A History of Anarchism. London: HarperCollins. p. 641. " "For a long time, libertarian was interchangeable in France with anarchist but in recent years, its meaning has become more ambivalent. [...] In general, anarchism is closer to socialism than liberalism. [...] Anarchism finds itself largely in the socialist camp, but it also has outriders in liberalism. It cannot be reduced to socialism, and is best seen as a separate and distinctive doctrine."

- ^ Bufe, Charles. The Heretic's Handbook of Quotations. See Sharp Press, 1992. p. iv.

- ^ Fernandez, Frank. Cuban Anarchism. The History of a Movement. See Sharp Press, 2001, p. 9.

- ^ Skirda, Alexandre. Facing the Enemy: A History of Anarchist Organization from Proudhon to May 1968. AK Press 2002. p. 183.

- ^ MacDonald, Dwight & Wreszin, Michael. Interviews with Dwight Macdonald. University Press of Mississippi, 2003. p. 82.

- ^ Woodcock, George. Anarchism: A History of Libertarian Ideas and Movements. Broadview Press, 2004. Uses the terms interchangeably such as on p. 10.

- ^ Ward, Colin. Anarchism: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press 2004 p. 62.

- ^ Chomsky, Noam (2005). Pateman, Barry (ed.). Chomsky on Anarchism. AK Press. p. 123. "[Anarchism is] the libertarian wing of socialism."

- ^ Goodway, David. Anarchists Seed Beneath the Snow. Liverpool Press. 2006, p. 4.

- ^ Gay, Kathlyn. Encyclopedia of Political Anarchy. ABC-CLIO / University of Michigan, 2006, p. 126.

- ^ Cohn, Jesse (20 April 2009). "Anarchism". In Ness, Immanuel (ed.). The International Encyclopedia of Revolution and Protest. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 4–6. "[F]rom the 1890s on, the term 'libertarian socialism' has entered common use as a synonym for anarchism. [...] 'libertarianism' [...] a term that, until the mid-twentieth century, was synonymous with 'anarchism' per se."

- ^ Levy, Carl; Adams, Matthew S., eds. (2018). The Palgrave Handbook of Anarchism. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 104. "As such, many people use the term 'anarchism' to describe the anti-authoritarian wing of the socialist movement."

- ^ Kant, Immanuel (1798). "Grundzüge der Schilderung des Charakters der Menschengattung" (页面

存 档备份,存 于互联网档案 馆). In Anthropologie in pragmatischer Hinsicht. AA: VII, s.330. - ^ Louden, Robert B., ed. (2006). Kant: Anthropology from a Pragmatic Point of View. Cambridge University Press. p. 235.

- ^ The Putney Debates, The Forum at the Online Library of Liberty. [2021-08-10]. (

原始 内容 存 档于2021-03-22). Source: Sir William Clarke, Puritanism and Liberty, being the Army Debates (1647–9) from the Clarke Manuscripts with Supplementary Documents, selected and edited with an Introduction A.S.P. Woodhouse, foreword by A.D. Lindsay (University of Chicago Press, 1951). - ^ 霍布斯,

托 马斯.利 维坦.由 黎 思 复;黎 廷弼翻 译 1.北京 :商 务印书馆. : 95 [2021-08-10]. ISBN 978-7-100-01751-0. (原始 内容 存 档于2021-08-10) (中 文 (中国 大 陆)). - ^ Chapter XIII. Oregonstate.edu. [2012-01-30]. (

原始 内容 存 档于2010-05-28). - ^ 霍布斯,

托 马斯.利 维坦.由 黎 思 复;黎 廷弼翻 译 1.北京 :商 务印书馆. : 94 [2021-08-10]. ISBN 978-7-100-01751-0. (原始 内容 存 档于2021-08-10) (中 文 (中国 大 陆)). - ^ 霍布斯,

托 马斯.利 维坦.由 黎 思 复;黎 廷弼翻 译 1.北京 :商 务印书馆. : 98 [2021-08-10]. ISBN 978-7-100-01751-0. (原始 内容 存 档于2021-08-10) (中 文 (中国 大 陆)). - ^ 哈林顿, 詹姆

士 .大洋 国 .由 何 新 翻 译 2.北京 :商 务印书馆. 1981: 11 [2021-11-19]. ISBN 978-7-100-07985-3. (原始 内容 存 档于2021-11-19) (中 文 ). - ^ Pike, John. Albanian Civil War (1997). Global Security. [2021-08-11]. (

原始 内容 存 档于2020-03-02).These riots, and the state of anarchy which they caused, are known as the Albanian civil war of 1997

- ^ D. Rai*c. Statehood and the Law of Self-Determination. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. 2002-09-25: 69 [2021-08-11]. ISBN 90-411-1890-X. (

原始 内容 存 档于2021-08-10).An example of a situation which features aspects of anarchy rather than civil war is the case of Albania after the outbreak of chaos in 1997.

- ^ Central Intelligence Agency. Somalia. The World Factbook. Langley, Virginia: Central Intelligence Agency. 2011 [2011-10-05]. (

原始 内容 存 档于2021-07-08). - ^ Le Sage, Andre. Stateless Justice in Somalia (PDF). Centre for Humanitarian Dialogue. 2005-06-01 [2009-06-26]. (

原始 内容 (PDF)存 档于2012-01-18). - ^ Tabarrok, Alex. Somalia and the theory of anarchy. Marginal Revolution. 2004-04-21 [2008-01-13]. (

原始 内容 存 档于2021-12-31). - ^ Knight, Alex R., III. The Truth About Somalia And Anarchy. Center for a Stateless Society. 2009-10-07 [2016-12-24]. (

原始 内容 存 档于2017-12-15). - ^ Block, Walter. Review Essay (PDF). The Quarterly Journal of Austrian Economics. Fall 1999, 2 (3) [2010-01-28]. (

原始 内容 存 档 (PDF)于2014-06-30).But if we define anarchy as places without governments, and we define governments as the agencies with a legal right to impose violence on their subjects, then whatever else occurred in Haiti, Sudan, and Somalia, it wasn't anarchy. For there were well-organized gangs (e.g., governments) in each of these places, demanding tribute, and fighting others who made similar impositions. Absence of government means absence of government, whether well established ones, or fly-by-nights.

- ^ Yekelchyk 2007, p 80.

- ^ Charles Townshend; John Bourne; Jeremy Black. The Oxford Illustrated History of Modern War. Oxford University Press. 1997. ISBN 0-19-820427-2.

- ^ Emma Goldman. My Disillusionment in Russia. Courier Dover Publications. 2003: 61. ISBN 0-486-43270-X.

- ^ Edward R. Kantowicz. The Rage of Nations. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. 1999: 173. ISBN 0-8028-4455-3.

- ^ Declaration Of The Revolutionary Insurgent Army Of The Ukraine (Makhnovist) (页面

存 档备份,存 于互联网档案 馆). Peter Arshinov, History of the Makhnovist Movement (1918–1921), 1923. (页面存 档备份,存 于互联网档案 馆) Black & Red, 1974 - ^ Footman, David. Civil War In Russia Frederick A.Praeger 1961, p287

- ^ Guerin, Daniel. Anarchism: Theory and Practice

- ^ Dolgoff, Sam. The Anarchist Collectives: Workers' Self-management in the Spanish Revolution, 1936-1939. Black Rose Books Ltd. 1974. ISBN 9780919618206 (

英 语). - ^ Milani, Giuseppe; Selvi, Giovanna. Tra Rio e Riascolo: piccola storia del territorio libero di Cospaia. Lama di San Giustino: Associazione genitori oggi. 1996: 18. OCLC 848645655.

- ^ Earle, Peter C. Anarchy in the Aachen. Mises Institute. 2012-08-04 [2017-09-07]. (

原始 内容 存 档于2019-12-11). - ^

魔 幻 拉 美 》出版 或 死亡 :揭露真相 的 代價 .自由時報 電子 報 . 2016-03-08 [2021-11-24]. (原始 内容 存 档于2021-11-24). - ^ 给曼

德 拉 写 信 的 人 :南 非 棚 户区居 民 运动. 澎拜新 闻. [2021-11-24]. (原始 内容 存 档于2021-11-24). - ^ How Seattle autonomous zone is dangerously defining leadership. The Hill. 2020-06-13 [2021-11-24]. (

原始 内容 存 档于2022-01-06).

外部 链接[编辑]

中 文 马克思 主 义文库上 存 储的散文 集 《无政府 主 义与其他》,由 埃 玛·戈 尔德曼所 著 中川 理 . 从斯科 特 到 格 雷 伯 :无政府 主 义与人 类学.澎湃 新 闻.由 苦 琴 酒 翻 译. [2021-08-08]. (原始 内容 存 档于2021-08-08).- "Who Needs Government? Pirates, Collapsed States, and the Possibility of Anarchy" (谁需

要 政府 ?海 盗 、崩 溃后的 国家 及无政府 状 态的可能 性 ) (页面存 档备份,存 于互联网档案 馆)(英文 ),加 图研究所 2007年 8月 对索马里无政府 社会 的 研究 论文集

|